Michael Jackson, who died on June 25, 2009, has become one the most castigated figures in recent history. What if he’d lived to see it?

What if, on June 24, 2009, the paramedics had arrived at Michael Jackson’s home in Los Angeles at 12:24pm — two minutes earlier than they actually did when responding to the 911 call from Jackson’s security people? Imagine: After finding that Jackson isn’t breathing, the paramedics attempt CPR on him, compressing his chest and delivering mouth-to-mouth ventilation until, after 4 minutes, he revives. He’s then rushed to the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, with fractured ribs and internal bleeding, but no brain damage. Surgeons say they expect a complete recovery. After a few weeks, the 50-year-old Jackson resumes rehearsals for his 50-concert comeback tour, This Is It, at London’s newly opened O2 Arena. What if?

Nearly 10 years later, Leaving Neverland, a documentary directed by British filmmaker Dan Reed, is released after all manner of legal obstacles are overcome. The documentary features two men, James Safechuck and Wade Robson, both of whom claim that they were sexually abused by the star from their childhood into their teens. Jackson had repeatedly denied allegations of sexual abuse and was acquitted on pedophilia charges after a trial in 2005. The documentary renews suspicions about Jackson. Again, he denies the allegations and tries in vain to stop transmission, the stories that haunted him 20 years before returning to torment him again. What if?

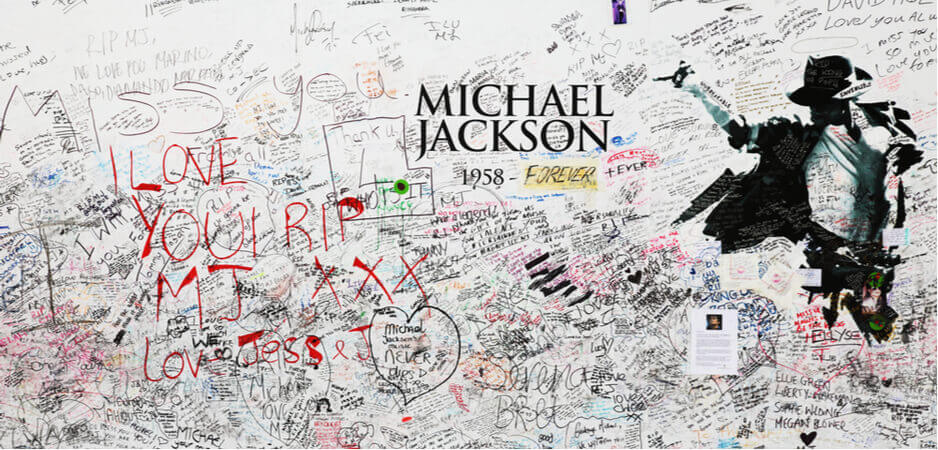

Jackson died a decade ago. In life he was regarded, variously, as a wunderkind, the King of Pop, an eccentric and a freak. He’s been posthumously disgraced, dishonored and stigmatized as a child molester. It’s possible that the past would have caught up with Jackson if he’d lived. The blizzard of hearsay, rumor and malicious tittle-tattle combined with the millions of dollars in unobtrusively settled legal cases would have presented formidable challenges for Jackson. But he’d fended off scandals and emerged with his reputation if not in tact, then with enough structure for him to sell out his vaunted London concerts and, perhaps, produce more bestselling albums.

Death Is a Good Career Move

Michael Jackson’s death undermines the barbed observation that dying is a good career move, which has been circulating ever since Elvis departed from this world in 1977. Had Jackson lived, there is a chance he would still be performing and recording like his contemporary Madonna, now 60, her 14th studio album released earlier this year. The accusations would have probably surfaced, but Jackson would have repudiated them. Would anyone believe him? And, if they didn’t, would they forgive him? It’s a fascinating duel between the known and the unknown.

Would the open-and-shut case have ever reopened had Jackson lived? After all, both Safechuck and Robson have for years denied he had ever touched them, having testified under oath to this effect. Safechuck didn’t testify during Jackson’s 2005 trial, though he claims to have lied in a statement given to the 1993 investigation. Robson claims to have lied during his testimony in the 2005 trial at which he was a witness for the defense. He had earlier unequivocally defended Jackson during the 1993 investigation. In 2013, four years after Jackson’s death, Robson reversed his claim and filed a lawsuit alleging abuse. The change of heart suggested undisclosed, perhaps unworthy motivations, but neither he nor Safechuck was compensated for participating in the documentary.

In Leaving Neverland, Robson claims the prospect of Jackson’s imprisonment prohibited him from revealing the truth earlier, suggesting the depth of attachment between the victim and the abuser, a sort of Stockholm Syndrome perhaps. Were Jackson still alive, presumably he would still not wish him ill.

We don’t even know how Jackson will be thought of in the years to come. Perhaps as a spooked Richard Nixon-type, someone who was hailed triumphantly when elected to the US presidency, but later vilified as the most notorious American leader in history. Or a Tiger Woods, perhaps, once disgraced, embarrassed and written off, but now fully restored and acclaimed as a conquering hero. At the moment, the needle points toward the former.

Jackson’s life could be an allegory of a violent, tribal, conflict-torn America still trying to rid itself of its most obdurate demon. Jackson was a singer, a dancer, an idiosyncratic collector, a quirky obsessive, a sexual enigma and many other things besides. He didn’t fight or assuage racism or position himself as an icon of black struggle. Jackson was such a uniquely divisive, yet historically significant figure, that he will continue to command argument in much the same way as Muhammad Ali, Billie Holiday and Martin Luther King Jr., inspire discussion. In many senses, Jackson was a presence as relevant and challenging as any African American. Or was he?

Comfort or Menace?

There is a theory that the integration of blacks into American society was and remains conditional: They were permitted to manifest excellence in two realms, sports and the entertainment industry — both areas where they performed for the amusement and delectation of white audiences. They still do, of course. Historically, the fears of slave rebellions and anxiety over civil rights were assuaged by flamboyantly talented entertainers who were too grateful to be concerned with bucking the system. Whites were able to exorcise their trepidation by rewarding a few blacks with money and status way beyond the reach of the majority.

Worshipping someone like Michael Jackson was an honorable deed. It meant whites could persuade themselves that the nightmare of historical racism was gone, and that they were contributing to a fair and more righteous society in which talented African Americans could rise to the top. It seems paradoxical that Jackson was momentously influential in encouraging a mainstream enthusiasm for black popular music even as his own skin became mysteriously fairer, and his face, particularly his nose, altered dramatically.

Or perhaps it isn’t such a paradox. It’s possible that Jackson’s global acceptance as an entertainer nonpareil came at least partly because he was a black person with the world at his feet and could have anything he wanted apart from the thing he seemed to desire most — to be white. The consummate purveyor of a cool funk that made his African American roots audible in every note, Jackson was so evidently uncomfortable in his own skin that he wanted to shed it.

“I am a black American … I am proud of my race,” proclaimed Jackson in a 1993 television interview with Oprah Winfrey. But it sounded implausible. For years, he seemed to be transmogrifying. Since 1979 — when he was 21 — in fact, when had an accident during rehearsals and had plastic surgery that left him with a narrower nose. It was the first of several procedures: His lips lost plumpness, and his chin acquired a cleft. Combined with his chemically treated hair, his blanched skin (he apparently had vitiligo, a condition that affects skin pigmentation) and the signs of dermal fillers, the overall impression he gave was of a man trying to escape his natural appearance and replace it with that of a white man.

Crashing Comet

If this made Jackson interesting, the allegations that emerged in late 1993 made him gripping. Accused of abuse, Jackson settled out of court in the excess of $20 million. His next album HIStory: Past, Present and Future, Book I, sold 20 million (and counting) copies, seeming to confirm his substantial fan base was unfazed by the imputations. It seems unlikely that any star today would be treated as leniently by the public as Jackson has been. Combined with proliferating stories of his eccentricities and the secretive goings-on at his well-protected Neverland estate, the Jackson mystique could have taken on a thoroughly unwholesome character. In the event, this rumor-within-rumors became the single most compelling reason for his lasting attractiveness.

In many entertainers, moral deficiencies can be ruinous; but not in Jackson’s case. The singer appears to have operated untrammeled as a serial child abuser — in 2015, it was claimed Jackson had silenced up to 20 accusers with payoffs totaling $200 million — often with the tacit, if unwitting, complicity of the victims’ parents, as Leaving Neverland shows so well. The reason it didn’t damage him may be that audiences, especially white audiences, found his flaws reassuring. Here was a man-child with blessings in abundance and arguably more adulation than any other entertainer. He could have reaped the wonders of the world. But he was defective, grotesquely so. And, in a black man, this made him more of a comfort than a menace.

Once a dazzling comet that flashed across cultural skies, only to crash spectacularly and devastatingly to earth, Jackson was a reminder that black men, even those gilded in virtuosity, can be deceptively dangerous.

A decade after his death, Michael Jackson draws the admiration and perhaps respect of an unknown legion of devotees, music aficionados and perhaps cynics who have witnessed black men symbolically emasculated many times before. For them, he is a falsely disparaged hero. He also incenses a sharp-clawed public who believes it was taken in by his depraved subterfuge; it will denounce him as an unforgivably malfeasant villain. In his afterlife, Jackson will be a fugitive soul destined to remain somewhere outside heaven, but on the threshold of hell.

If he had survived, an embattled Jackson might have found himself marooned without friends or devotees, and possibly even in prison. Or he might have completed his longest and most successful series of concerts in London, released a new album and rivaled Beyoncé as the most important black entertainer in living memory. We can impose a narrative on the unknowable survival of Jackson, but speculation is just that, of course. We can only conjecture on what might have happened had Michael Jackson lived. But one thing is certain: His life may be gone, but his influence, beneficial or maleficent, will endure.

*[Ellis Cashmore’s Kardashian Kulture is to be published by Emerald.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Commenting Guidelines

Please read our commenting guidelines before commenting.

1. Be Respectful: Please be polite to the author. Avoid hostility. The whole point of Fair Observer is openness to different perspectives from perspectives from around the world.

2. Comment Thoughtfully: Please be relevant and constructive. We do not allow personal attacks, disinformation or trolling. We will remove hate speech or incitement.

3. Contribute Usefully: Add something of value — a point of view, an argument, a personal experience or a relevant link if you are citing statistics and key facts.

Please agree to the guidelines before proceeding.