Religious leaders such as the Aga Khan may be difficult to decipher in Western contexts.

On March 14, the governor of Georgia presented a state proclamation to Prince Shah Karim al-Hussaini, the Aga Khan, the spiritual leader of Shia Imami Ismaili Muslims. The proclamation recognizes the Aga Khan as the 49th hereditary imam, tracing direct lineage to Prophet Muhammad through his daughter Fatima.

There are not many occasions when state entities recognize a religious leader, and a Muslim one at that. It is, therefore, worthwhile to understand the Aga Khan’s work and the interpretation of Islam that he represents.

The proclamation makes reference to the Aga Khan’s “longstanding commitment to improving the human condition” and his work in the global South through the development institution that he founded over 50 years ago, the Aga Khan Development Network. The network operates in more than 30 countries and has a broad scope, which includes education, health care, financial services and cultural and environmental preservation.

At first glance, the Aga Khan appears to be like any other rich philanthropist — another Bill Gates or George Soros perhaps, using his private wealth to venture into previously colonized worlds to rescue its people through service delivery. That, in fact, is one of the ways in which the Aga Khan is popularly viewed in Western contexts: a philanthropist, a social entrepreneur, a do-gooder.

The reduction of the Aga Khan’s work to these trendy idioms, though well-meaning, is misguided. It significantly narrows the scope of his efforts, which he grounds in the faith of Islam. Philanthropy, in the American context, has developed over the course of the 20th century as a way for individuals to deploy their private wealth for the good of the people. Such individuals have also often been able to mold public policy to align with their visions.

However, it is precisely this ability of private actors to influence public policies that makes scholars suspicious of “big” philanthropy. Run by private boards with broad agendas, philanthropies yield extensive political power without public accountability, while relying on public funds and tax breaks for their operation.

Additionally, while some philanthropic endeavors have religious affiliations, increasingly many more are distinctly secular. The emergence of the latter in the West has taken place in a context where religion is presented as a conservative force leading toward intolerance, while notions of tolerance and justice are often linked with secularism — even as scholars have delineated the religious roots of secularism. Religion and religious people, thus, are popularly viewed as being out-of-place in the contemporary moment. Such sentiments make religious leaders such as the Aga Khan difficult to decipher in Western contexts.

The Aga Khan has previously explained:

I am fascinated and somewhat frustrated when representatives of the western world — especially the western media — try to describe the work of our Aga Khan Development Network in fields like education, health, the economy, media, and the building of social infrastructure. Reflecting a certain historical tendency of the West to separate the secular from the religious, they often describe it either as philanthropy or entrepreneurship. What is not understood is that this work is for us a part of our institutional responsibility — it flows from the mandate of the office of Imam to improve the quality of worldly life for the concerned communities.

This mandate calls on him to safeguard the individual’s right to personal spiritual search and to give practical expression to the ethical vision of society that the Islamic message inspires. In this worldview, faith and the world become intricately linked. The imam must therefore advance the welfare of his followers across both domains and help them to understand the interconnections.

For instance, the Aga Khan’s articulation of the purpose of education is significantly broader than the reduction of education to a means for accumulating wealth, which we find prevalent in society today. Instead, the Aga Khan notes that the acquisition, production and transmission of knowledge should be guided by a desire to understand and appreciate Allah’s creation. It should also enable one to make a positive contribution to one’s communities and societies. This does not mean that education cannot be deployed to advance material well-being; rather, it posits that accumulation of wealth must be in keeping with the ethics of Islam.

These ethics include generosity, kindness and public welfare. Education, then, should teach us about our interdependencies and the responsibilities that we have to each other. Per the Aga Khan, it should guide us to share our knowledge and competencies to pull up those around us. Such an approach to education would perhaps rein in the unbridled greed and individualism that is so pervasive today.

If there is one key message to take away from the Aga Khan’s visit, it is to make space for Muslim ethical framings of care for the self, community and others. It is crucial to reject the reduction of Islam to only interpretations that breed intolerance. Islam has, is, and will remain an enormous force of good and social justice in the world. And the Aga Khan powerfully represents that aspect of Islam.

*[Note: This piece has been updated to give the date of the proclamation as March 14 instead of March 12.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

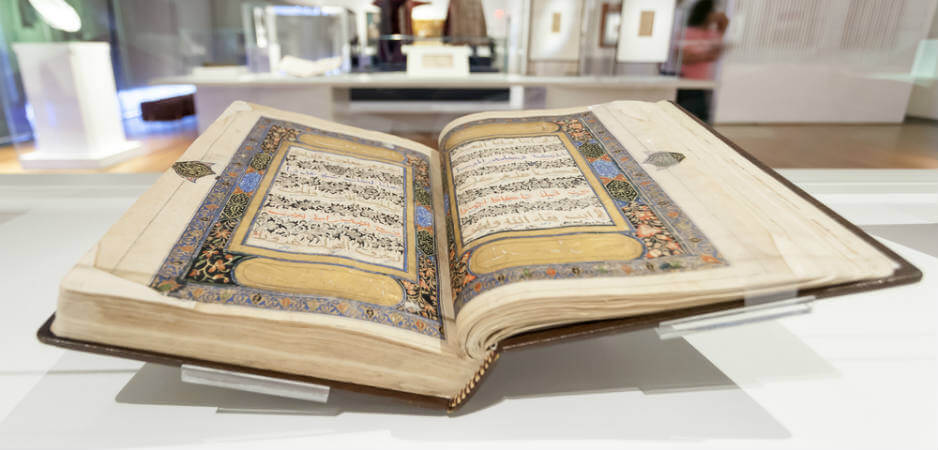

Photo Credit: Philip Lange / Shutterstock.com

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.