The first celebrities of the 20th century were men of courage and heroic endeavor.

What is the definition of celebrity? It’s probably something along the lines of people being famous for nothing other than the fact that they are themselves. Has celebrity always meant the same thing across the ages? What did it mean at the turn of the 20th century, before the cataclysmic wars that changed the world forever? It meant something more heroic — people with more to offer than just themselves.

In Edwardian Britain, with gnawing self-doubt and imperial glory beginning to fade, Britain needed its famous to be of a heroic kind, either by deed or by irrefutable genius. The public hero needed to embody qualities that the British had long championed as part of its national identity: brave, dignified, modest and resolute in the face of adversity. This had become particularly important with Britain caught in an arms race with Germany and mounting tension between European nations. What sort of men — and they were exclusively men, of course — matched this heroic model of fame? Step forward the Antarctic explorers of the early 20th century.

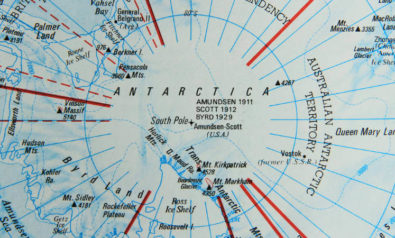

Antarctica is the coldest, driest, highest and windiest continent on Earth. Its surface area is slightly larger than Europe and doubles in size in winter when half the Southern Ocean freezes. The lowest recorded temperature on Earth was taken at -89.2°C on Antarctica’s high interior. At these temperatures a steel bar will probably shatter if dropped.

As the most inhospitable place on the planet it is remarkable to contemplate that a little over a hundred years ago this dangerous place became an obsession for explorers. As the last unexplored continent, developed nations began to compete in its discovery in the quest to gain knowledge but also to claim new land. The race for the South Pole had begun, and the men who risked everything exploring the terrifying icy wilderness became some of the most fêted heroes across the world. These intrepid Antarctic explorers were the 20th century’s first celebrities.

First Into the Unknown

The British were the first to organize major Antarctic expeditions under the auspices of the imperious president of the Royal Geographical Society, Sir Clements Markham. He had developed a life-long passion for polar exploration since his naval service in the search for Sir John Franklin, who had perished with all his men when looking for the fabled North-West Passage in the Arctic in the 1840s. This epic tale of suffering was a tragic episode of exploration that was sensationally reported across the globe. The tenacious Markham successfully promoted his great cause with an initially disinterested public and national media. He was set on appointing a Royal Navy officer to lead the last big adventure for humankind on Earth. He chose a protégé, Robert Falcon Scott, a man with no polar experience.

Scott commanded the Discovery expedition (1901-04) with an official purpose to carry out scientific work but Scott, Ernest Shackleton and Dr. Edward Wilson also marched south to within 410 miles of the Pole, setting a new record. The media across the globe eagerly awaited information from these pioneers who had trudged some 850 miles, been forced to kill their weakening dogs to feed the living and suffered scurvy, exhaustion and malnutrition.

Popular newspapers were eager for news of untainted heroes: They wanted triumphant tales of men bravely pitting themselves against nature and claiming seemingly unconquerable lands. This was especially true of British newspapers that had recently been reporting on the Boer War, a messy conflict with Dutch settlers in South Africa that had revealed Britain was not invincible.

When Scott arrived safely back in Britain, despite some criticism about the public cost and the extent of the expedition’s achievements, he became a celebrity overnight. This intense, thoughtful and reflective man was appalled at his new status. For Scott it was all for king and country, even if personal ambition to advance his position in life had played its role in propelling him forward.

In interviews and public speeches, Scott played down the dangers he and his men faced, endearing him even more to the public. He became the darling of London society, receiving royal invitations and securing his place as the leading explorer of Antarctica. A gifted writer, Scott’s lyrical book on the expedition sold out quickly. It was a blockbuster that gave the public what it expected from a hero. Meanwhile, his personal anxieties and worrying bouts of self-doubt were concealed. The private Scott — who was very much a product of the Victorian “stiff upper lip” — was never reconciled with the celebrity Scott.

Courting Publicity

Watching from the sidelines was the ever-restless Ernest Shackleton, whose larger-than-life exploits might well be fiction rather than fact. The Anglo-Irish merchant seaman had succumbed to a blinding passion for Antarctica; in his own words he wrote that he felt the “call of the South.” His early grueling attempt to reach the South Pole under what he perceived to be the rigid command of Scott proved that he needed to be the leader of his own expedition.

Shackleton was a more gregarious and volatile character than the reserved Scott, and he was much more comfortable when it came to courting publicity and giving the public what they wanted. The two men became intense rivals—although it was still a British insular kind of rivalry without it being played out in the press or tempered by the arrival of Antarctic explorers from countries with superior knowledge of ice and snow. Financed largely by his own fundraising efforts rather than with the official backing enjoyed by Scott, the charismatic outsider was mounted his own expedition on the Nimrod (1907-09).

Shackleton’s expedition reached just 97 miles from the Pole: an extraordinary achievement that nearly killed his team. When he returned, he was greeted ecstatically by a fervent public, and the newly-knighted charmer then set about creating a cult of celebrity. Shackleton was a master of the art of public relations, giving many entertaining interviews, filling lecture halls across Britain and even making a gramophone record with his stirring account of the southern journey.

Shackleton’s first solo Antarctic expedition had all the right ingredients to make him a national hero: a triumph against all odds plus a heroic near miss. Although his presentation skills were superior, he was less of a writer than Scott, yet his book too sold out. As conflict with Germany loomed Britain needed a gallant hero and Shackleton was more than willing to be one.

The Final Race to the Pole

The final race to the Pole played out between Scott’s last expedition on the Terra Nova (1910-13) and the Norwegian Fram expedition (1910-12), under the much more experienced polar explorer Roald Amundsen. The Norwegian’s expedition started out as an attempt on the North Pole but, on hearing of American claims to have reached it, he decided to go for the South Pole. Amundsen kept his plans secret from most of his crew and backers, fearing he would be stopped.

This was typical of Amundsen, a meticulous professional explorer who did not court the distractions of fame despite his own fascination for the dramatic tales of polar exploration. Two months into his voyage, Amundsen announced to the world his plans to head south, sending a clipped cable message to Scott, whose ship was in Australia en route to the Antarctic: “Beg leave to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctic. Amundsen.” The race was on.

Compared to the British, Amundsen’s party had superior knowledge of cold-climate travel and their use of dogs and skis proved far more suitable to the terrain than Scott’s reliance on ponies and man-hauling. Amundsen claimed the South Pole for the relatively new nation of Norway on December 14, 1911. Scott arrived 33 days later only to find evidence of Amundsen’s victory. Scott’s demoralized party of five, suffering from gradual starvation, hypothermia and almost certainly scurvy, died on the grim march home. The ice-covered malnourished bodies were discovered seven months later.

Before the news of Scott’s tragic death reached the world, Amundsen was the center of global media interest when his ship sailed into Tasmania. Australia’s reporters quickly learned that their newspapers were clearly not the communication medium that Amundsen would use to distribute his epic news. Amundsen had sold the publication rights to newspaper in London reinforcing Britain as the hub of information about Antarctic exploration.

The canny Norwegian understood that how he disseminated news of his victory needed as much planning as reaching the Pole itself. Yet within a year, Amundsen’s immense achievement was eclipsed by the tragic news that the British polar party had perished. Despite the rivalry, Amundsen was devastated by the news and distressed to find that he had somehow found himself cast in the role of villain by a chauvinistic British press. Lacking the personality for embracing the limelight like Shackleton, the cool and calculating Amundsen was characterized as the underhand foreigner, who had somehow cheated by using dogs to haul sledges.

During 1912, British newspapers were waiting for Scott to check Amundsen’s story about reaching the South Pole first. The Times of London, on March 9, 1912, nearly a year before the news broke around the world that Scott had died, quipped passive-aggressively: “… whatever we think of the way in which he [Amundsen] set about it, we congratulate his success.” At a public dinner hosted by the Royal Geographic Society in London where Amundsen was a guest, its president, Lord Curzon, raised a toast: “… and three cheers for the dogs!” The Norwegian felt suitably insulted, prompting him to quantify the British in his memoir as “a race of very bad losers.”

The race to the South Pole was over. Amundsen had been the victor but he had not played the game by British rules. He had become infamous, something the Norwegian never recovered from.

For Britain, which was about to be torn apart by the First World War, there was an overwhelming need for wholesome selfless heroes. Scott was the epitome of the amateur Victorian gentleman on a quest for scientific knowledge and a grand adventure that was as much a psychological test of national character as it was of the individual. The media played an essential role in Scott’s metamorphosis into an immortal noble icon. The discovery of his diary — found under his frozen body — mesmerized the public. His dying words, including the self-sacrificing account of Captain Oates walking out of the tent to his death, stirred hearts. As he wrote, “Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell … which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman.” Scott’s fame grew after his death into a heroic cult as his public image of un-self-pitying bravery in the face of adversity became embedded in national consciousness.

The Stuff of Fiction

Despite the conquest of the South Pole and the vast national outpouring of grief over Scott’s death, Shackleton planned to return to Antarctica. His new daring plan was to cross the Antarctic continent via the South Pole — an idea that had been proposed by other explorers and was now the last clear Antarctic challenge. He was restless at home away from the action and this was his last chance to fulfill his ambitions. Shackleton tirelessly sought official backing and eventually managed to raise support and money for his grand scheme on the eve of war

His Endurance expedition (1914-17) set off to cross Antarctica but the ship became trapped in pack ice, drifting 700 miles north before sinking. Shackleton and his men camped on the ice, still moving north, until he could launch his three ship’s boats in open water and reach the relative safety on Elephant Island, 100 miles away. Shackleton and his crew were castaways on an uninhabited island. No one would look for them there and they did not have enough food to last the winter. He quickly decided to take five others and sail the 22-ft James Caird to seek help from South Georgia. The expedition’s photographer captured the agonizing wait for Shackleton on Elephant Island — pictures that would later convey the essence of the immense test of human endurance.

The epic 800-mile winter boat voyage took 17 days and remains one of the most remarkable ever undertaken. The boat was cramped, constantly wet, and bailing was non-stop, making rest impossible. Their clothes were tattered and drenched by salt water. Navigation was particularly difficult, with only a few sightings of the sun and missing South Georgia altogether would have meant certain death.

Shackleton was then forced to cross the island to reach the Norwegian whaling stations on the north coast, over unmapped, icy mountains up to 3,000 feet high. Exhausted and ill-equipped, he set off with the two fittest men and provisions for three days only. They had to climb steep mountains, backtracking on several occasions. Not daring to sleep, they covered about 40 miles in 36 hours only stopping to eat a hot meal every four hours. They eventually reached the whalers in May 1916, seven months after the Endurance was abandoned. The station manager knew Shackleton but did not recognize the “terrible trio of scarecrows” at first.

Shackleton asked: “Tell me when was the war over?”

The Norwegian whaler replied: “The war is not over, millions are being killed. Europe is mad. The world is mad.”

With the First World War raging in Europe, the British government was slow responding to the half-forgotten Shackleton. It took a fourth relief attempt to pick up the men on August 30, 1916. Miraculously, all had survived.

Pray for Shackleton

As the decades have passed, the public reputations of Scott, Amundsen and Shackleton have been re-evaluated as perceptions of what deserves admiration and hero status have shifted. Initially, Scott’s poetical writing and tragic death doing his duty for king and country ensured he remained the quintessential British imperial hero for generations whose face could be seen on everything from cigarette cards to history books for children across the globe.

Come the 1960s and revisionist history, Scott’s heroic status — along with other heroes of Britain’s empire — was dismantled as part of the rebellion against the establishment. Since the 1990s, Shackleton has emerged from the shadows to a newly-found celebrity status on both sides of the Atlantic- that of the modern leader — the man to lead you out of a crisis. The outsider in the race to the Pole suddenly felt very in tune with the turn of the 21st century.

The same can be said of the highly proficient Amundsen, who was marginalized in Britain during his lifetime for his well-executed plan for reaching the South Pole first. A contemporary once wrote about the men’s differences: “Scott for scientific method, Amundsen for speed and efficiency but when disaster strikes and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.”

With today’s technological advances, the Antarctic explorers’ particular kind of heroic celebrity cannot be replicated. Living in the age of the internet and limitless connectivity, it’s incredible to think that the first men on the moon had more contact with civilization than the early 20th century explorers. Whatever the meaning of celebrity, fame and heroism today, these men did capture the public imagination in their lifetimes and their remarkable stories of human endeavor, courage and bravery will always lift the human spirit.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Mlenny

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.