Germany and Mexico must remain vigilant to prevent public perceptions from negatively impacting their asylum, refugee and migration policies.

Germany is facing the most important immigration crisis in its history since World War II. The recent attacks that took place on three consecutive days in Munich, Reutlingen and Ansbach broke the fragile peace that reigned in the country after the Islamic State-linked attacks in Würzburg and Hanover earlier this year. These unfortunate events, which are all regarded as part of the latest wave of terrorist attacks to hit Europe, have renewed criticism toward the open-door asylum policy that German Chancellor Angela Merkel has vehemently pursued and defended.

The fact that the state of Bavaria was the main point of entry for many refugees and the target of the recent attacks by asylum seekers has left a bitter feeling among Germans. Just months ago, German citizens had warmly welcomed refugees arriving on board the trains from Hungary following their treacherous journey from Syria and other areas of the Middle East and across eastern Europe.

In 2015, many homes and buildings in Munich, Berlin and other German cities displayed signs of “Welcome, Refugees.” Now, the so-called immigration crisis has politically polarized German society. Today, popular demands and proposals to swiftly combat the terrorist threat have taken the place of such welcoming attitudes.

Increasing Security or Infringing Rights?

Increasingly, some sectors of German civil society are openly calling to review and retract the freedom of movement and political liberties that the country granted to and upheld for its citizens and inhabitants until just recently. So far, some of the demands that seem to be gaining ground in the political discourse in Germany include: setting stricter border controls within the Schengen area and German borders themselves; expanding personal data holding programs on German and foreign citizens; increasing the number of police officers on the streets of Bavaria and the rest of Germany; and even using the army to safeguard public places.

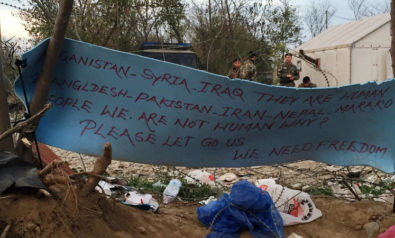

Worryingly, many of such demands and the resulting policy proposals are aimed specifically at two particularly vulnerable groups: new immigrants and refugees. They include, for instance, the decision to process the deportations of irregular immigrants more expeditiously (regardless of human rights concerns of doing so), and monitoring refugee camps more closely (therefore, blurring the line between sanctuary and ghetto).

Bringing the issue of immigration to the realm of national security has created a dilemma between the German government’s priorities and societal preferences. Until recently, Merkel and her cabinet had directed the government’s attention and efforts at promoting and sustaining the image of Germany as a country willing and eager to become a haven for persecuted and displaced people from around the world—especially from the Middle East.

After the recent attacks, however, some sectors of society appear to believe that Germany’s borders, police and military forces cannot adequately protect them from global terrorism and organized crime. Increasingly, immigrants and refugees in Germany are seen as a danger that must be addressed and controlled. Hence, the government’s priority has rapidly shifted toward regulating immigration flows and managing and enforcing its borders more strictly.

Perceptions and Policy in Historical Perspective

As with any other government, the kind of immigration policy that the German government pursues and sustains is also based on the perceptions that its people have about borders and immigrants. Should the immigration phenomenon be perceived as an opportunity, the government’s priority will then move away from security and enforcement and on to the effective integration of immigrants into society for its benefit. Achieving this latter objective is not only possible, but has already been done in previous decades.

During the 1950s, the German Federal Republic welcomed the Gastarbeiter (guest workers) in response to the labor shortages that followed World War II. In need of rebuilding itself but facing a shortage of low-skilled labor, the government recruited mostly male workers from Italy, Spain, Yugoslavia, Greece, Portugal, Tunisia, Morocco, South Korea and Turkey through bilateral agreements with these countries set up in collaboration with West German employment offices.

The programs were generally considered successful. By the end of the boom years of foreign recruitment in 1973, the level of qualification of these workers remained relatively low, and most of them were employed and remained in low-skilled jobs. This issue had not been of concern to the government or the public. It was thought that the program responded only to the temporary demand for labor and that, by the end of it, foreign workers would simply leave. Nonetheless, when the workers did not leave and instead permanently settled in the country, German society gradually integrated them—albeit not without problems.

New Immigrants, New Challenges

The experiences of today’s immigrants to Germany, however, have been very different from those of their counterparts in the early 1960s. First, their arrival is not the outcome of a search for better job opportunities, but a forced departure from their homes in Syria, Afghanistan, Serbia, Kosovo, Iraq, Albania, Eritrea, Pakistan, Somalia and Ukraine due to wars and domestic conflicts. Such conflicts have caused a wave of asylum applications that has been steadily rising since 2011.

This phenomenon, along with an increase in the number of immigrants from the European Union, has brought the total number of foreigners in Germany to 10.9 million—a figure with which not all sectors of the German population feel comfortable.

On the one hand, some sectors, including the German left and the Social Democrats (CDU), as well as a large number of intellectuals, look favorably on the open-door policy of Germany and the arrival of refugees. On the other hand, there are groups like PEGIDA, or Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West, and the radical right. These groups argue that “uncontrolled” immigration from the Middle East has exacerbated the prevailing social and economic disparities existing in the country and has disrupted and threatened their lives and German society as a whole.

The perception of foreigners as a threat to Germany has become a headache for the country’s government and institutions. Initially, Merkel had sought to show a “friendly face” to refugees, which she upheld with more conviction than most of her fellow party members in the Christian Democratic Party. Now, she is being pressed into choosing between helping refugees, or responding to the demands of the public and her party to take a tougher stance on the fight against immigration.

Germany and Mexico compared

Surprisingly, the political debate and infighting that Germany is currently undergoing to ensure the civil liberties of its people while protecting the security of the country has parallels with Mexico. While Mexico has historically been a source country for migrants, from the 1940s onward, it also started to become a host country. Therefore, it has experienced similar problems to Germany.

In those years, Mexico witnessed the arrival of tens of thousands of refugees from the Spanish Civil War, as well as others escaping from European countries that had been invaded by Nazi Germany. Similarly, three decades later, a large number of Lebanese, Argentines and Chileans left for Mexico, fleeing civil wars and political persecution in their countries. Likewise, in the 1980s, Mexico welcomed and became a transit country for millions of refugees from the civil wars in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala.

Subscribe to Fair Observer for $10 a month and we will gift you our e-publications and invite you to inspiring events.

Subscribe to Fair Observer for $10 a month and we will gift you our e-publications and invite you to inspiring events.

Immigrants, especially refugees, were perceived in a positive light in Mexico, and their status in the country benefited from such a view. At that time, for instance, Mexico’s policy of open arms toward Central American refugees sharply contrasted with the unwavering refusal of the United States to provide asylum. Such perceptions and policies resulted in one of the largest increases in the number of immigrants to the country. By 2000, the number of Central American immigrants in Mexico had reached about 40,000 people. In 2015, that figure had surpassed the 60,000 mark.

With the rapid increase of immigrants, including those en route to the US via Mexico, perceptions about migrants soon changed and their circumstances in Mexico quickly degraded. Law enforcement agents as well as criminal groups began profiting from human trafficking across Mexico’s borders, while Mexicans in general began developing a negative view of immigration, especially from Central America. Consequently, immigration policies toward the region began hardening.

Paradoxically, the discrimination and xenophobia that many Mexican migrants still endure in the US were reproduced by Mexico’s government and citizens against Central American immigrants. For instance, in 2015, Mexico deported more Central American immigrants than the US. In Mexico, just as in Germany, borders began to be thought of as “floodgates” against the immigration upsurge.

The Impact of Popular Perceptions on Immigration Policy

It is worth noting that in Mexico, just as in Germany, the government does not regard immigrants as a national security threat. On the contrary, Mexico has traditionally been a refugee receiving country and, over the last decades of the 20th century, it also became a transit country. However, at the dawn of the 21st century, the country started receiving more and more immigrants. Increasingly, it has become a reluctant host to many Central American migrants who have escaped the wave of violence that has hit their countries and have failed to enter the US.

Such a rapid increase in the number of immigrants is an issue of concern to the Mexican government. Without adequate attention and support from the government, it is thought that such groups could become an economic burden to society or even a potential risk to public safety. One of such concerns, for example, is that if they are not provided with employment alternatives, they could be recruited by organized crime groups.

Views such as these have led individuals in both countries to speak of immigrants and refugees in the 21st century as “qualitatively different” to those who arrived in the 20th century. While the immigrants and refugees of the 20th century are usually considered as integrated socially, economically and culturally, their counterparts of the 21st are regarded as a collective threat to the security and wellbeing of Germany and Mexico.

Such a view of immigrants as a “danger” has alienated both local populations and newcomers. This hinders the effective communication, adequate integration, collaboration and mutual support that are the pillars of any society.

By toughening their immigration policies, Mexico and Germany are not only closing the doors to a social phenomenon that inevitably accompanies economic, political and social globalization. They are also breeding a critical mass of tension and mistrust within their countries which, as seen in Germany, could lead to harmful and deplorable attacks against civilians.

To meet these challenges, Germany and Mexico must seek progressive and sustained integration of newcomers. In the search for solutions, immigration should be understood as a complex and heterogeneous phenomenon, produced by economic differences between countries; historically-rooted patterns in bilateral relations; family and community ties; and political or humanitarian crises, such as those that have created the current flows between the Middle East and Germany, and Central America and Mexico. Unfortunately, many of these issues appear to be increasingly disregarded in the current immigration policies of both countries.

Restoring tolerance, restoring security

A large number of civil society groups in Mexico and Germany seem to have radicalized their attitudes and perceptions toward immigrants and refugees. For conservative groups and politicians in both countries (although more evidently in Germany), immigrants have become a “danger” to be contained. In domestic and international contexts marked by insecurity, terrorism and organized crime, the radicalization of such a discourse has led to the exclusion (and, in extreme cases, persecution) of immigrants and refugees, making these groups even more vulnerable.

The radicalization of anti-immigrant discourse makes both societies more likely to witness hate crimes within their borders—making them, in turn, more insecure for everyone. Germany and Mexico must remain vigilant to prevent public perceptions from negatively impacting their asylum, refugee and migration policies.

In previous decades, immigration to these countries had been a source of prosperity and well-being to both immigrants and host societies. By all means, Germany and Mexico could still see such a tolerant and mutually beneficial relationship restored early in the 21st century.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Dinosmichail

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.