On January 28, the Islamic Resistance in Iraq, an Iranian-backed group, launched a successful and lethal drone attack on Tower 22, an American military outpost in northeast Jordan. Three US service members were killed and 47 more wounded. While Iran-backed groups have been attacking US positions across the Middle East since the outbreak of the Israel–Hamas war last October, this was the first strike to kill US soldiers.

The attack has prompted strong demands in Washington and elsewhere for a powerful US response. Instead of targeting the various groups in Iraq sponsored to one degree or another by the regime in Tehran, advocates call for striking at Iran directly. Such a response might involve disrupting Iran’s petroleum industry by bombarding the relevant facilities.

The demands for a strong kinetic response are countered by warnings about the US being drawn into a wider regional war in the Middle East. The unsuccessful American military effort to stop the Taliban’s control of Afghanistan and a less ambitious but equally unsuccessful intervention in the Lebanese civil war in the mid-1980s provide reasons for caution.

So, the alternatives — at least those discussed in public — are either continued tit-for-tat responses to attacks by Iranian-sponsored bands in Syria and Iraq or direct measures against Tehran with the accompanying danger of an escalatory spiral leading to a large-scale regional war. The latter would lead to a growing number of American military casualties, which would have to be absorbed in a presidential election year.

There is a third way, one well worth consideration by policy-makers and members of the American public.

How the US can exploit Iran’s weaknesses and avoid bloodshed

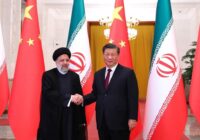

The Islamic Republic is a formidable adversary. Its political and military leaders, from Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, to President Ebrahim Raisi, Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) head Hossein Salami and Quds Force commander Esmail Ghaani, have shown themselves to be quite ruthless and adept in maintaining their grip on power. To this end, they are aided by the IRGC, an organization of some 150,000–190,000 fighters or potential fighters. The IRGC is, in turn, divided into the Quods Force, whose tasks include foreign terrorist operations in the Middle East and beyond, and the Basij an organization devoted to the maintenance of internal security — by all means necessary, including torture.

Despite a political culture of religious repression and the weapons available to a modern police state, the Islamic Republic is not invulnerable. By many accounts, the regime is highly unpopular, especially among the educated middle classes of Tehran and the other major cities. Also, whether deserved or not, the regime has acquired a reputation for corruption, particularly among leaders of the IRGC.

Iran’s population is close to 88 million, a significant proportion of whom are young people under the age of 20. At last count, the country’s unemployment rate was around 10% of the workforce. These figures suggest a less than contented population.

Public protests against the Islamic Republic are hardly out of the question. The most spectacular of these manifestations so far was the sustained protests by Iranian women following the death in custody of a young woman, Masha Amini, arrested for not wearing her hijab appropriately. Beginning in September 2022 and continuing into 2023, the forces of repression had to be employed throughout much of the country.

Furthermore, the Iranian population is less than homogenous; aside from the majority Persian ethnicity, there are Azeris, Kurds, Balochis and Arabs. In past decades, leaders of these communities have sought to achieve greater autonomy from Tehran, sometimes by the use of violence, albeit short-lived.

This combination of demographic and political characteristics point to some of the Islamic Republic’s vulnerabilities, ones that might be exploited by the United States, at least in the long-run. Subversion appears to be a sensible means of weakening the regime of the ayatollahs. The Central Intelligence Agency has extensive experience in weakening various hostile regimes in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, not to mention the successful 1953 coup it promoted against the nationalist regime of Muhammad Mosaddegh that brought the Shah back to power.

[Anton Schauble edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment