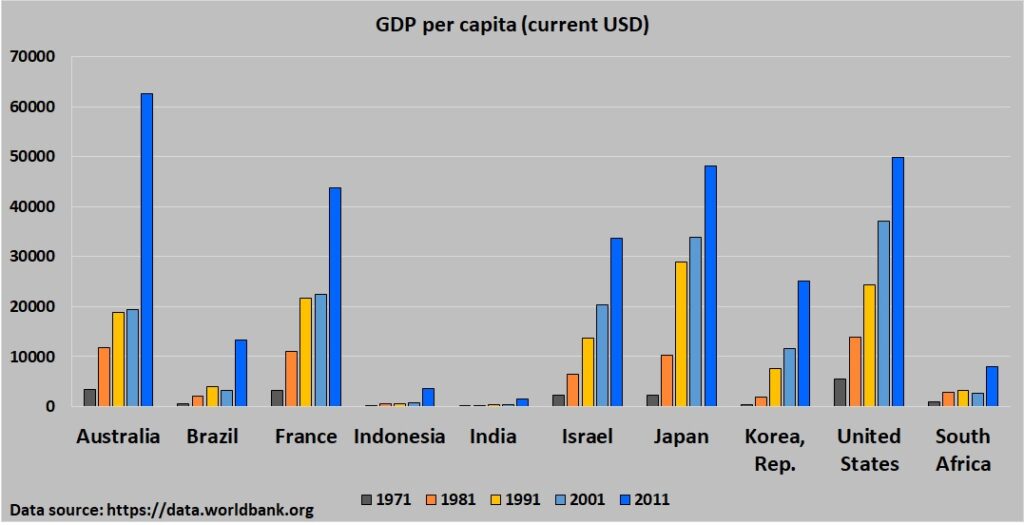

Over the 18th and 19th centuries electric power fueled industrial revolutions in the UK, US and several European countries. In the last century countries like Japan and the Republic of Korea too leveraged it to develop economically. More recently, it has aided tremendous economic growth in China. Investment in power generation and distribution helped uplift these countries both economically and socially.

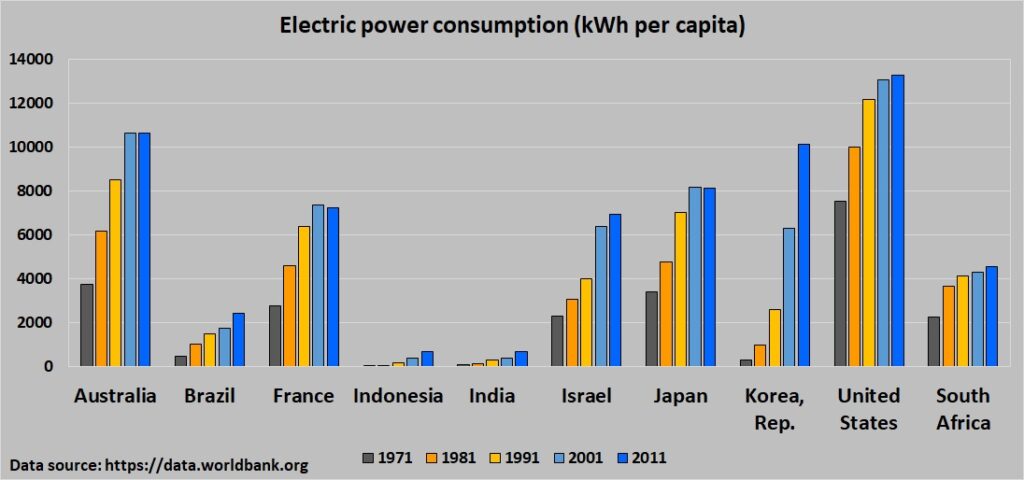

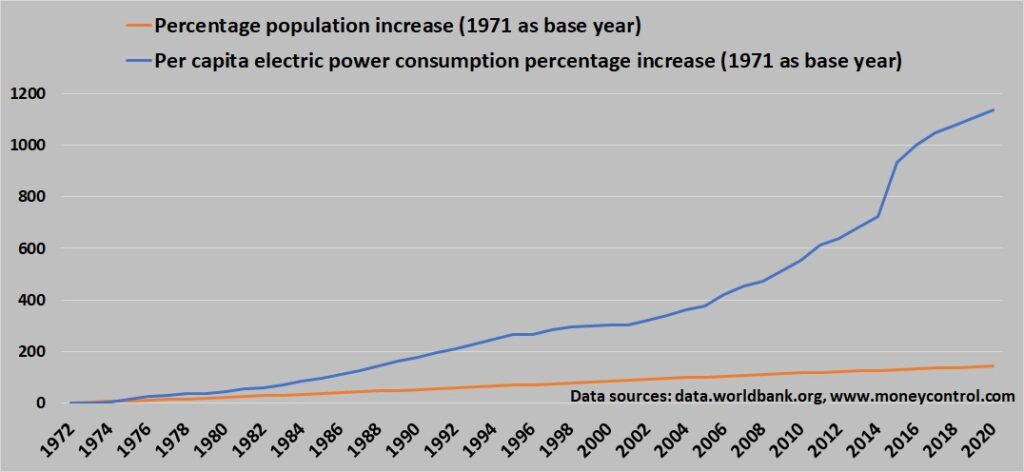

In 1971 India’s and China’s gross domestic products (GDP) stood at par at USD 118. India’s per capita power consumption in that year was 98 kilowatt hours (kWh), China’s was 152 kWh. Forty years on, China’s GDP had risen to USD 5618, nearly fifty times the GDP in 1971. In the same year, India’s GDP stood at USD 1458, a modest twelve-fold increase from the GDP in 1971. China’s power consumption in 2011 had risen to 3296 kWh. India’s was a distant 696 kWh.

About a fifth of India’s population was estimated to be living below the poverty line in 2012. Approximately 50% of India’s population is categorised as middle class. India has over 900 million people in the 15-64 age group. Over 360 million are under 14 years of age. This section of the population is also growing at a much faster rate than that of the overall population. Viewed from the perspective of current prosperity levels or population distribution based on age groups, today more than ever before, India needs to ensure sustained employment for its present and emerging workforce. An increasing GDP lifts people above the poverty line and makes more money available to the middle classes for investment in healthcare, security and education. Improved income and education levels also reduce crime.

While China has leveraged lessons of several countries by investing in economic infrastructure, India has failed to do so for much of its independent history.

The weight of socialism on power sector

When India gained independence in 1947, its per capita power consumption was 16 kWh, far short of what the country needed for socioeconomic growth at pace. At that turning point in its history, India adopted the Soviet socialist model. The state stayed heavily invested in industry for several subsequent decades. On one hand, this prevented human resource capability and private enterprise from developing to their potential. On the other hand, key enablers for socioeconomic development – education, health, highways or power – were starved of sufficient investment.

USSR’s collapse in 1991 served as a trigger for India to embrace economic reforms. Private companies began investing in power generation. But given the huge power shortfall built over decades, along with growing demand subsequently, the investment over 30 years has been far short of what’s needed for sustained economic growth.

Power transmission and distribution continue to be mostly state-controlled. Power distribution companies (discoms) have borne the brunt of this model. Political parties make populist electoral promises – ranging from subsidised electricity to waiver of past dues – and compel discoms to honour those if they form governments. Repeated election after election in many states, this populism leads to discoms charging on average less per unit than they buy electricity for, pushing them to default on payments to generating companies. This situation deters private investment in power generation.

The impact of this deep-rooted problem is not limited to the power sector. When power generators are unwilling to continue supplying power on credit, governments are compelled to bail the discoms out for them to pay generation companies. Bailouts are done at the cost of modernisation and expansion of power infrastructure, as well as investment in key sectors like healthcare and education.

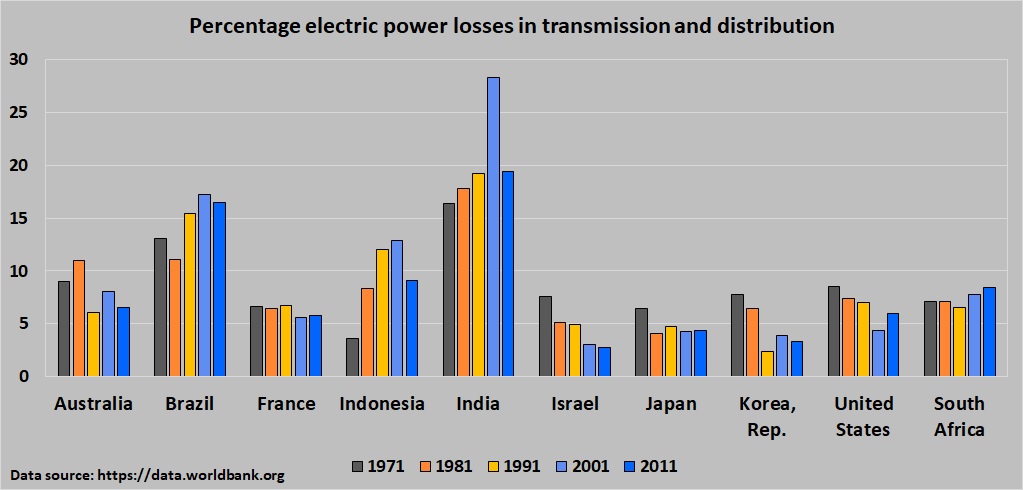

Power loss by theft and technical causes is another systemic problem.

These deep-rooted problems have since long made a compelling case for further reforms in the power sector.

The reforms journey over 30 years

In 1991, India opened power generation to private investment, which led to increased power generation in the country. Despite the sector’s many challenges, consumers in both rural and urban India benefited. By 2018, electricity reached every village.

For several decades after independence, electricity was treated as a scarce commodity. If the post office, health care clinic and key facilities had power supply, then the electrification of the village was deemed done. This narrow definition of electrification was expanded in 1997 and 2004. If 10% of homes in a village have power supply, then it is deemed to be electrified.

Governments have repeatedly attempted further power sector reforms with varying degrees of success.The 1998 Electricity Regulatory Commissions Act of and the 2003 Electricity Act were introduced to establish national and state regulatory bodies for rationalizing tariffs and subsidies as well as streamlining the transmission and the sale of power. These initiatives did not achieve their core objectives. Hence, in 2015 the government launched Ujwal Discom Assurance Yojana, UDAY to revive discoms financially and operationally. Given the depth of discoms’ problems, which were further complicated by COVID lockdowns, UDAY fell short of achieving its objectives after some early successes.

Some successes are noteworthy. Many states have taken steps to control theft. In the prime minister’s constituency, electricity authorities have implemented new technology to detect illegal connections. This has reduced power theft and increased legal power connections. Such initiatives have indeed lowered power losses but these are still over twice the global average.

In 2020, the government announced an economic stimulus package of over $3 billion to revive a pandemic-battered economy. This included an injection of liquidity yet again for discoms. In 2021, the government announced a result-oriented package for discoms, which included introducing smart grids and smart meters across the country. These ambitious initiatives are expected to benefit discoms by reducing operational costs, checking theft and giving consumers detailed data about their electricity usage. India has also set up a national grid, connecting the five regional grids. This will strengthen the transmission network across the country, ensuring more even power distribution.

These reforms are noteworthy. They are a step in the right direction and will increase per capita power consumption. However, the core problem of the power sector — the government control over discoms — still remains unaddressed.

Lighting up the road to development

India’s power minister aspires to increase per capita power consumption threefold — the same level as the global average. The time has come to broaden the definition of electrification yet again. Only when 20-30% of a village has access to electricity should it be considered electrified. Furthermore, the successes in implementing new technologies must be institutionalized and implemented across the country.

Today, private companies are contributing significantly to India’s power needs. Privatisation of discoms is the long overdue big ticket reform. To this end, the government introduced the Electricity Amendment Bill in 2021. This proposes a rationalization of subsidies and introduces other key reforms such as a push towards renewable energy. The bill promises to improve the financially parlous state of most discoms and incentivize private investment in the sector.

In 2020 the government proposed transformative agriculture reforms, which led to a year of protests. Ultimately the government withdrew the legislation. This was a huge setback for economic reforms. The 2021 electricity bill has similarly run into rough weather, forcing the government to climb down.

Hardships caused by over two years of the pandemic and yearlong protests have reduced the government’s appetite for reforms. It is unlikely that significant reforms will be rolled out before the next national elections in 2024. The ruling National Democratic Alliance (NDA) won large majorities in the 2014 and the 2019 elections. In 2024, the NDA faces a tougher challenge.

If the opposition wins, reform is unlikely. The opposition parties are wedded to left-leaning failed policies of the past. However, if the NDA wins decisively, it will have political capital to spend on reforms. Then, it may address the power sector’s core problem that has cost the country tremendously over many decades. In this term, the NDA government sold off the failed nationalized airlines Air India to the Tatas. In the next term, the NDA could finally privatize dysfunctional, loss-making and tax-guzzling discoms, generating more light in the nation.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment