No less than 969 million people out of India’s population of 1.4 billion are voting from April 19 to June 1 in the world’s biggest elections ever. They will decide who will be the next Indian prime minister. Across 28 states and eight union territories, officials who organize the elections may walk 30–50 kilometers (20–30 miles), sometimes at high altitude, to record a single person’s vote, making these elections a herculean logistical feat.

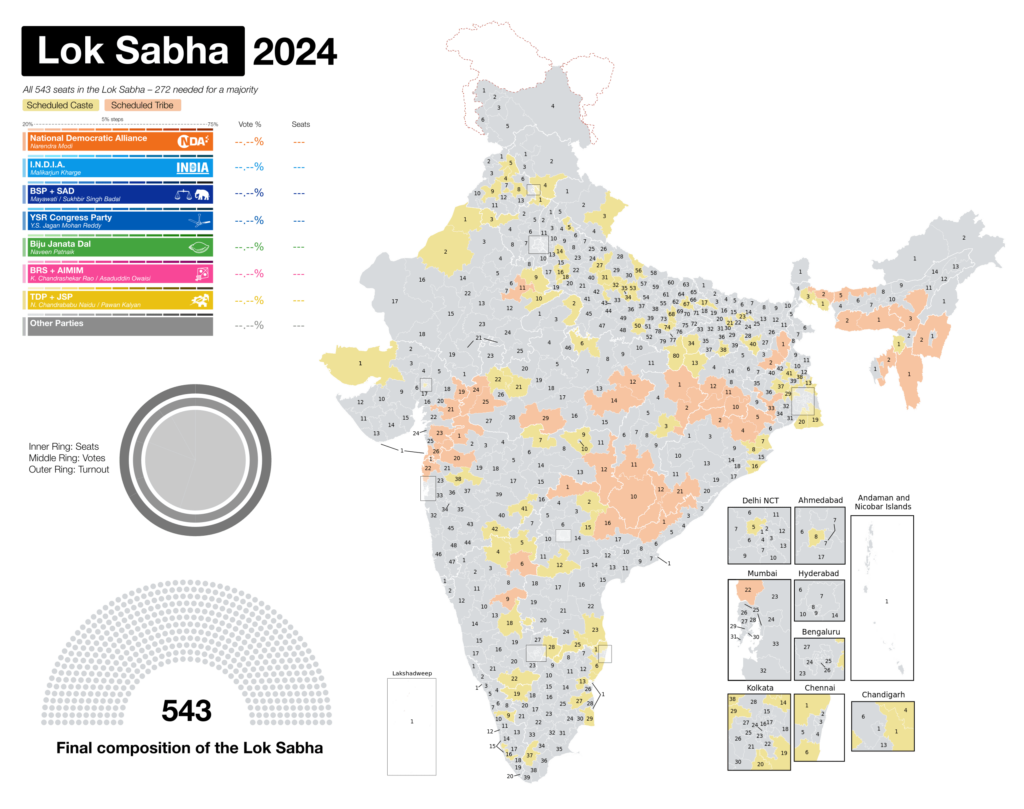

Modeled after Great Britain’s Westminster system, India is a parliamentary democracy. After all, Westminster ruled India for nearly two centuries — indirectly through the East India Company from 1757 to 1858 and then directly from 1858 to 1947 when India achieved its independence. This year, from May to June, citizens will vote for members of parliament (MPs) in the lower house, called the Lok Sabha. Parties are contesting 543 seats, and the leader who commands 272 MPs (a 50% + 1 majority) will become prime minister. The results are set to be announced on June 4.

Electoral map of India. Via ExactlyIndeed on Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Who are the key players in the Indian elections?

Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been in office since 2014 and is likely to win a historic third term. The BJP is a right-leaning nationalist party which opponents call Hindi fascists or Hindu supremacists. These critics allege, often with much exaggeration, how minorities feel threatened in India. In particular, Muslims are said to be under siege. Notably, Modi is India’s first backward-class prime minister — a set of communities deemed to be historically disadvantaged because of India’s inequitable caste system — and is popular both amongst India’s middle class and its poor.

Even opponents praise Modi for targeted welfare programs. He has distributed free food grains to a staggering 813.5 million people. His government gives low-income women a monthly stipend of 1,200.50 rupees (approximately $16) and also provides cheap sanitary napkins for better menstrual health. The Modi government has built sanitation systems, provided piped clean water and delivered cooking gas cylinders throughout India. Naturally, poor women tend to vote for the Modi-led BJP.

Related Reading

Modi’s main contender is the left-leaning Indian National Congress (INC), which once led the freedom struggle. The INC has a rich history and was once democratic but now has become a dynastic fiefdom of the Nehru dynasty. Jawaharlal Nehru was India’s first prime minister and the son of a famous INC leader Motilal Nehru. He was a Fabian socialist who looked up to the Soviet Union but kept his distance from Moscow. Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi (no relation to Mahatma Gandhi) jumped enthusiastically into bed with the Soviets and amended the constitution to declare India a socialist country. Indira’s grandson Rahul now is the leader of the INC, and he is running on a populist leftist platform, promising freebies to the public such as monthly cash transfers, increased subsidies, more government jobs and generous pensions.

There are other opposition parties in addition to the INC. They are often regional parties, but they tend to be more dynamic than the INC. The new Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) rules Punjab and Delhi. In the southern state of Tamil Nadu, which elects 39 MPs to the Lok Sabha, the established Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) is in power led by M.K. Stalin (who is neither a love child nor relative of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin).

The border state of West Bengal elects 42 MPs to the Lok Sabha. This state is the western half of the historical Bengal, which was partitioned between India and Pakistan in 1947. (East Bengal eventually declared independence 1971 and became Bangladesh.) Today, Mamata Banerjee, who left the INC when the Nehru family failed to give this regional satrap her due, rules West Bengal.

What are their records and what lies ahead?

The Modi government has done a great job building infrastructure. They are constructing roads, ports and railway lines day and night. Nitin Gadkari has been an exceptional minister of road transport and highways. Many middle-class Indians want him, instead of Modi, to be prime minister.

The Modi government has also built digital infrastructure. It has reduced the infamous leakage in government welfare programs. Rajiv Gandhi, Rahul’s father, once admitted that only 15% of the disbursed amount reached the intended beneficiaries. By implementing a national identity card scheme, opening bank accounts for hundreds of millions and delivering benefits directly to their accounts, the Modi-led BJP government has reduced theft dramatically. Hence, Modi has a reputation for competence and the BJP has replaced the INC as the dominant party in Indian politics.

Yet Modi has made some wrong calls too. In 2016, he imposed demonetization — withdrawal of high-denomination currency notes — with no notice. This destroyed small businesses around the country and, in part, caused the unemployment crisis that India is suffering today. He practices what one of the two authors has called Modi’s policies Sanatan socialism.

Related Reading

Modi has made business and entrepreneurship a lot easier in this historically socialist economy. However, he still relies heavily on the bureaucracy, particularly the colonial, corrupt and spectacularly incompetent Indian Administrative Service (IAS). Policymaking continues to be haphazard, and the IAS still remains arbitrary. Businesses suffer because of a lack of policy certainty as well excessive regulation.

In fact, even members of the BJP and its parent organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), complain about Modi’s excessive centralization of power. Some BJP and RSS leaders go so far as to say that Modi is Indira Gandhi “true son” because of his absolutist tendencies. They even complain that Modi runs an IAS government with mere outside support from the BJP and the RSS.

Related Reading

For all his faults, Modi is still more free-market than opposition party leaders. The INC is promising Latin American-style populism to voters, which would derail growth and could even bankrupt the government. So, Modi is benefiting from what Indian political analysts call the “there is no alternative” (TINA) factor.

[Gwyneth Campbell wrote the first draft of this piece.]

The views expressed in this article/video are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Comment