What the heck is going on in Russia?

Yevgeny Prigozhin, leader of the private military force called Wagner Group, riveted global attention last month. Prigozhin took elements of his 25,000-strong private army away from the Ukrainian front and led them on an abortive drive to Moscow. The open rebellion even included capturing the major Russian city of Rostov, where generals overseeing the Russian war effort are based. His claimed goal was to secure the firing of Sergei Shoigu, Vladimir Putin’s bungling defense minister whom Prigozhin accuses of sabotaging Wagner’s efforts in Ukraine.

When all was said and done a short 24 hours later, however, Prigozhin had given up, ostensibly accepting a sort of exile in Belarus while allowing the regular army to absorb his troops, leaving international observers bewildered. Putin had labeled Prigozhin a traitor and vowed to bring him to justice just hours before. Why would Prigozhin give up without a fight?

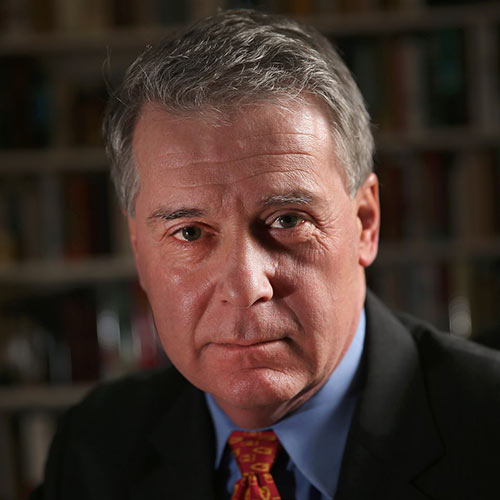

Glenn Carle, a retired CIA man and no stranger to the psychology of power, adds context to the story. The glory from Wagner Group’s capture of the Ukrainian city of Bakhmut was fading. The regular army was taking legal steps to sideline Prigozhin, remove his influence and co-opt his troops. Prigozhin seems to have taken the last possible chance, while he still had a position, to make a bid for influence. He may have been afraid for his life, thinking that his rivals would seek revenge after he lost influence. It is also likely that alcohol abuse was affecting his mental state.

Glenn reminds listeners that Yevgeny Prigozhin is no military genius. He is driven and brutal, but he is essentially still a street thug that got lucky. There may have been no grand strategy behind his surrender; plausibly, he simply gave up after the support he was hoping to see from segments of the military failed to materialize. After all, a force of 25,000 men is not all that much in a nation of over 140 million.

Western onlookers were no doubt excited by the prospect of Putin’s regime collapsing due to a rebellion, and when the rebellion failed they comforted themselves with the narrative that the Putin regime was at least now weakened, the dictator appearing vulnerable. Glenn dismisses this analysis. Sure, Putin’s dictatorship is brittle, but all dictatorships are. Something brittle is strong until it breaks. As long as he is in power, Putin retains the ability to assert his control and to punish anyone who opposes him, as he is certainly willing to do. Scores of former Putin opponents met their ends drinking a teacup doped with poison; why should Prigozhin expect anything different?

Ukraine is in trouble. Western resolve is more fragile than Russian resolve, and Putin knows it. This Prigozhin kerfuffle is unlikely to have any substantial impact on the war. If it is to survive in its present form, Ukraine must defeat the Russians on the battlefield, overcoming their formidable defenses and pushing them out of the country tactically, not attritionally.

The country’s economy was already crippled before the Kakhovka dam disaster left half a million hectares of cropland without a source of irrigation. In a country that supplies a significant chunk of global cereal supplies and over half of its sunflower oil, the downstream effects can be enormous.

At the end of the segment, Glenn fields some viewer questions. Glenn compares Wagner Group with the American private military company Blackwater and discusses the likelihood that American or Ukrainian intelligence services were involved in the debacle.

[Anton Schauble wrote the first draft of this piece.]

The views expressed in this article/video are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Comment