Pundits say Obama is on a roll, but in what other year has a US president been rebuked by three of his defense secretaries?

The new narrative among the punditry caste is that US President Barack Obama finished 2014 on an unexpected high note that will carry over into the new year. In this telling, his executive action on immigration policy, climate change pact with China and surprise normalization of relations with Cuba — along with an improving economy and dramatically falling energy prices — have allowed the president to shake off the disastrous political rebuke he suffered in the mid-term elections in November.

This perspective has already generated some fulsome commentary, such as a New York Times columnist opining that “President Obama is acting like a man who’s been given the political equivalent of a testosterone boost.” Of course, the immigration and Cuba actions took place in the vacuum of a lame-duck Congress. Things will look very different once newly-installed Republican majorities begin work on Capitol Hill. Already a senior Democratic lawmaker is warning of Senate difficulties in appointing a US ambassador to Havana, and plenty of budget battles loom in the months ahead.

Moreover, the new wisdom overlooks the leadership dysfunctions and management problems that have long plagued the Obama administration and which will surely trip it up going forward. The president has done little to suggest he will fix the policymaking machinery inside the White House that has been widely criticized as chaotic and excessively centralized. As one long-time Washington observer put it just four months ago: “Obama seems steadfast in his resistance both to learning from his past errors and to managing his team so that future errors are prevented. It is hard to think of a recent president who has grown so little in office.”

The White House Hole

All three men who have served as Obama’s defense secretaries punctuated this criticism in 2014. Robert Gates, the much-respected national security professional who served as the president’s first Pentagon chief, kicked things off a year ago with the publication of his long-anticipated memoir. The book was harshly critical of the White House’s management style, calling it “by far the most centralized and controlling in national security of any I had seen since Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger ruled the roost.” He also complained that Obama’s national security inner team was drawn from the ranks of campaign aides who “took micromanagement and operational meddling to a new level.”

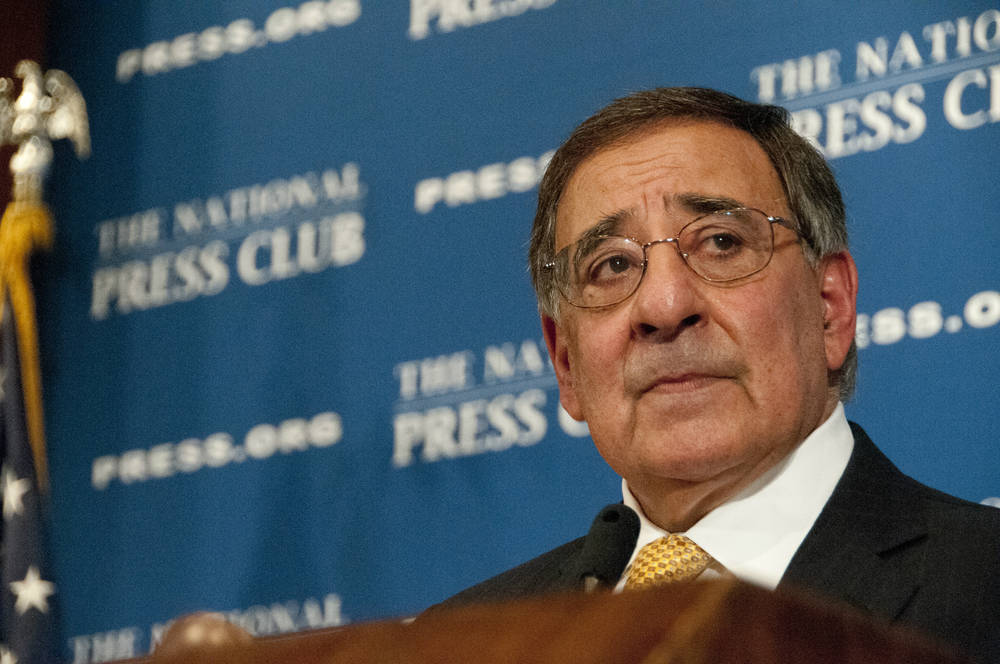

These themes were then repeated later in the year when Leon Panetta, Gates’ successor, published his own memoir. A Democratic Party elder statesman who earlier served as White House chief of staff for President Bill Clinton, Panetta wrote: “Far more than in previous administrations that I’d witnessed — certainly more than in Clinton’s when I’d been near the center of the action — President Obama’s decision-making apparatus was centralized in the White House.” He noted that Obama’s reliance on senior White House staffers was so heavy that Cabinet members were largely frozen out of the policy formulation and implementation process.

A Reuters report appearing just as Panetta’s book was published corroborated these points. It quoted a former senior US official as saying that meetings involving even Cabinet members were little more than “formal formalities,” with the real decisions made by the president and a handful of White House aides. Soon afterward, a New York Times article noted that with Obama leaning more than ever on a small circle of White House staffers, Cabinet secretaries were “struggling to penetrate the tightly knit circle around the president and carve out a place in the administration.” It claimed Secretary of State John Kerry is so disconnected from the White House that staffers “joke that he is like the astronaut played by Sandra Bullock in the movie Gravity, somersaulting through space, untethered from the White House.”

Gates and Panetta renewed their criticisms in a joint appearance at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in November. The former said, “It was micromanagement that drove me crazy” and related how the White House staff went so far as to install a direct telephone line with the Afghanistan headquarters of the Joint Special Operations Command. (Gates says he insisted that the line be torn out but, according to The Washington Post, staffers’ calls to field commanders have since resumed.)Panetta joined in, noting: “Because of that centralization of authority at the White House, there are too few voices that are being heard … You go there, and by the time you get to the White House, the staff has already decided, or tried to influence, what the direction should be.”

Hagel’s Turn

By the time the two had spoken, Obama had just ousted Chuck Hagel, his third defense chief. The move was interpreted by a New York Times report as representing “the final triumph of a White House-centric approach to national security.” It added that shortly after the announcement of Hagel’s departure, the president “walked over to a meeting of his entire National Security Council staff, where he told the embattled group that they were critical to an ambitious foreign policy agenda.”

While Obama staffers quickly put out that Hagel’s dismissal was due to his laconic leadership style, his own circle countered that the real problem was the White House’s chaotic management of national security policy. As this author has noted elsewhere, this is a long-running criticism of the Obama policy set-up, and just a few weeks before Hagel renewed it, Politico quoted a recently departed senior administration official as saying: “[T]here is a sense that the [National Security Council] is run a little like beehive ball soccer, where everyone storms to wherever the ball is moving around the field. They are managing by crisis rather than strategy … It’s Syria one day, Iraq the next, North Korea the next, and so on. The NSC is finding multitasking very hard these days.”

The Washington Post recently reported on how vastly inefficient this process is. As the White House pondered the military’s request to keep 10,500 American troops in Afghanistan following the end of the NATO combat mission, it convened “14 meetings of NSC deputies, four gatherings involving Cabinet secretaries and other NSC ‘principals,’ and two NSC sessions with the president.” The result of this activity: The request was pared back by just 700 troops — to 9,800.

The Daily Beast relates that a similar process is hindering the US effort against the Islamic State. It notes that White House decision-making has:

“… been manic and obsessed with the tiniest of details. Officials talk of sudden and frequent meetings of the National Security Council and the so-called Principals Committee of top defense, intelligence, and foreign policy officials (an NSC and three PCs in one week [in October 2014]); a barrage of questions from the NSC to the agencies that create mountains of paperwork for overworked staffers; and NSC insistence on deciding minor issues even at the operational level.”

The publication also quoted a senior defense official as saying: “We are getting a lot of micromanagement from the White House. Basic decisions that should take hours are taking days sometimes.”

This dysfunction has placed unnecessary strain on the national security bureaucracy, with one analyst noting: “[T]he National Intelligence Council, a place supposed to be doing high-level analysis and providing much-needed foresight to the U.S. government, ended up devoting much of its bandwidth to providing an estimated 500 background briefing papers for the absurdly frequent NSC principals and deputies meetings that took place in the past year.”

Politico relates that Obama now feels liberated to be “the president he always wanted to be.” But the problem with unleashing the “inner Obama” is he is only as good as the people and the process he has installed in the White House.

Fair Observer is a nonprofit organization dedicated to informing and educating global citizens about the critical issues of our time. Please donate to keep us going.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Mykhaylo Palinchak / Imagemaker / Albert H. Teich / Shutterstock.com

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment