With frequent mass shootings in America, what leads people like Chris Harper-Mercer to pick up a gun and murder others?

Guns don’t kill. People with guns don’t kill (most of the time), even when there are a lot of them, as in the United States today. Cultures that worship guns do kill. And cultures that conceive of killing as the ultimate form of justice kill repeatedly and on a grand scale.

With the recent mass killing in Oregon on October 1, the liberal commentators, starting with President Barack Obama, are repeating with increased exasperation their traditional message: guns are too readily available. Amid the weeping, voices cry out telling us that laws must be changed to prevent such acts. These voices are supported by facts and statistics derived from mountains of research from the US itself and the rest of the world. Because most Americans have deep respect for the Constitution and the rule of law, they believe specific laws are effective means of regulating behavior. For liberals, things will be better when we devise the proper laws to respond to new problems. By the same reasoning, those on the conservative side who oppose “big government” are particularly hostile to anything that smacks of “regulation.” For them, behavior must not be constrained by new laws or anything that restricts what they believe are the basic constitutional freedoms.

The vocal faction that defends what they call “gun rights” are probably right when they affirm that changing the laws and imposing gun control wouldn’t have a serious impact on human behavior, especially in cases like this latest mass killing in Oregon. Before exterminating nine victims, the killer himself, referring in his blog to the former television reporter in Virginia who recently assassinated two people on air, offered this analysis: “People like him have nothing left to live for, and the only thing left to do is lash out at a society that has abandoned them.” Laws are only effective with people who have something to live for. Furthermore, laws designed to prevent lashing out are hard to imagine and, if passed, are unlikely to have a direct effect on actual behavior.

The media have already begun focusing on these two perennially newsworthy questions: Who was Chris Harper-Mercer, and how did he procure the weapons that allowed him to kill nine people on a quiet campus in Oregon?

Calling it a problem of mental illness—“stuff happens” in the words of one presidential candidate—comforts the notion at the heart of the neo-liberal economy that we are a society of autonomous self-interested decision-makers, some of whom are tainted. The tainted will inevitably act unpredictably, so maybe Jeb Bush is right. Insisting that with better laws such incidents will be statistically less likely to occur may prove marginally true, but it doesn’t mean that what happens in Australia will automatically produce the same effects in the US.

To seriously address this issue and even begin to hope for long-term solutions, we would do better to go beyond the now traditional alternative of focusing on laws (the Democrats) or mental illness (the Republicans), and instead look a bit more deeply into the multiple layers of the culture that regularly coughs up these murderers in our schools, malls and churches. It’s considerably more complex than the usual analysis offered by politicians, whether from the right or left or the pundits in the media.

Guns: The flower on the tree

There is no doubt that US gun culture lies at the heart of the problem. The fact that Laurel Harper-Mercer, the murderer’s mother, happens to be a gun loony (not just a gun nut) bears out that conclusion in this particular case. But contrary to standard liberal orthodoxy, the obsession with owning and even displaying guns in public is less the cause than the symptom of something else—something more deeply embedded in US culture as a whole.

A culture is defined not by its superficial habits and actions, but by its core values. Values may be experienced and manifested actively or passively. All members of a culture are affected by those values, even when they consciously reject them. Those values that are most deeply established and transformed into abstract ideas are the hardest to change.

Gun culture was born from converging mythologies having to do with various factors: political independence, manifest destiny, the conquest of the west, the belief in “selfless” foreign wars and the myth of the self-reliant pioneer who must defend himself against both nature’s wildest forces and evil groups of people, ranging from Indian tribes to bandits. These associations have contributed to forging widely shared values that enable a good proportion of the population to see the gun as both a pragmatic tool for safety and security and a symbol of the individual as a force for virtue in a hostile world. But beyond these often cartoonish associations, there are other cultural layers that converge to produce a terrain favorable to the actions of a typical mass killer.

Every culture elaborates a set of assumptions about how challenges are met and problems dealt with. US culture has consistently elevated and rewarded action over thought as a general principle. This may help to explain the appeal of Donald Trump as a presidential candidate. (Again, it’s worth noting that Laurel Harper was not only a gun looney, but also a Trump fan, long before the real estate mogul began dabbling in politics; she boasted of reading passages of Trump’s Art of the Deal to her son prior to his birth twenty-six years ago).

Trump is perceived by his fans as an entrepreneur who gets things done. The capacity for “getting things done” should be recognized as one of the layers of cultural value at play in all these killings. Its simplest expression can be found in the Nike slogan, “Just Do It.” In the 1993 Arnold Schwarzenegger film Last Action Hero, a young boy is in a cinema watching the scene where Laurence Olivier as Hamlet hesitates to kill his guilty uncle Claudius. As Hamlet reflects, the boy cries out “don’t talk, just do it!” He then fantasizes a trailer for a modern version of Hamlet featuring Schwarzenegger’s heroic takedown of Claudius and all of Hamlet’s other enemies, accompanied by a voiceover intoning, “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark … and Hamlet is taking out the trash.”

One thing that appears to be common to almost all mass killings is the perpetrators’ conviction that something is rotten in their life, a feeling of isolation and marginalization. They are sure that they have been treated like trash. They then identify a category of people they in turn may deem to be trash, which may or may not include actual people who have offended them, but usually becomes an anonymous group—such as Christians or other believers for Harper-Mercer, African Americans for Dylann Roof and young women for Elliot Rodger. When they begin their attack, this category of trash to be eliminated then expands to include anyone who happens to be in their sights. It appears that Mercer-Harper wrote in his manifesto: “Many will ask how can they have prevented this? You can’t. You could never give me what I wanted. Nothing could have stopped it.” Action was required, just as it was for the updated Hamlet played by Schwarzenegger.

That this action-first attitude has become a prominent feature of US culture is borne out in the political sphere. A nation founded by a group of reflecting, debating and deliberating intellectuals—the founding fathers—has now turned into a public stage given over to simplistic, formulaic opposition, increasingly intolerant of the “cost” of thinking, reflection and analysis, as well as to the idea of adapting to a reality that cannot be reduced to a few glib slogans. George W. Bush’s precipitation to cut short debate and invade Iraq in 2003 is an obvious example of action before thought.

This process can be seen to be at work with regard to other phenomena, such as systematically contesting the authority of science and the refusal of one side of the political spectrum to take climate change seriously. In the mind of many Americans, science represents thought and study; economic activity represents action.

That is why it literally becomes urgent to do nothing about climate change. It would be a sin to interrupt or postpone positive action (industrial activity) for the sake of speculative science. On the other hand, when science produces new possibilities of action—for example, 70 years ago with the atomic bomb or more recently with drones—there is no hesitation to embrace scientific progress. Science to achieve a purpose is good; science to understand and adapt to the world in which we live is a waste of time, energy and especially money, a luxury we can’t afford.

So let us put science to work, engage it in action, especially focused on military technology. After all, that’s what gave us the Internet and GPS as well as new generations of deadly weapons. Afterward, even if the results appear to be appalling from a moral point of view, there are no regrets because getting the job done is more important than worrying about the consequences.

Paradoxically, studies and polls show that a majority of Americans actually do believe the science and are not opposed to reflection, even if they consistently fail to produce a legislative majority. This points to an essential political paradox: What people think and what cultural inertia imposes when decisions are to be made may well be two different things in any culture.

The current cultural logic of the US, promoted by Republicans but to a large extent shared by Democrats, tells us that there are two kinds of people: actors (the doers or makers) and passive receivers (the beneficiaries of what the makers allow to trickle down). It certainly isn’t science, but it’s the kind of “common sense theory,” a trope that spreads through the culture to become a widely accepted belief transmitted by multiple cultural vectors, including the media, the popular arts and education.

The sacred virtue of self-reliance tells us that those who act—the doers—will succeed. And of course those who haven’t succeeded have necessarily failed to act, possibly because like Hamlet, they have spent too much time thinking about justifying their eventual actions. That is how cultural values work even in the face of scientific reasoning. This is true even of those members of society who know how to put their inherited background values in perspective. Those culturally determined values somehow retain the ability to overcome explicit forms of reasoning. We end up accepting them unwittingly and reluctantly for some or enthusiastically for others as an inevitable feature of our reality.

Linked to the idea of success for the self-reliant is another typically American value: assertiveness. In most languages, there is no direct equivalent to this quintessentially American virtue. French is at a total loss to translate it; no similar idea in French culture exists, let alone a single word. Reluctantly some people accept, for the purposes of translation, the imported notion of assertivité, but most French people don’t recognize it and cannot comprehend what it might mean. (For fairly obvious reasons, this is not the case in Québec.) Chinese requires a combination of ideas, including the character for “excessive” to express the notion, which is natural for a culture that sets harmony as its highest ideal.

Assertiveness is seen as the key to successful action in US culture. The profile of all mass killers reveals personalities that suffer from their awareness of having failed to be assertive. They consequently conceive an act that will, at one fell swoop, compensate for that failure.

Superior values: executing justice

But the reverence for action alone, even within a gun culture, doesn’t explain the penchant for what is usually called “senseless” killing—the term senseless being required to distinguish it from various forms of socially justified killing. Even in an action culture, killing is too extreme an act to be routinely condoned. Even when violence is enthroned in the name of the masculine value of assertiveness, no culture can justify the act of killing as a virtue in itself.

To enable socially acceptable killing—whether in war, law enforcement or in private—there must be other references, superior values, that justify such extreme behavior. Those values are generally enshrined in mythology and sanctioned by law and/or tradition. In some Middle Eastern societies, for example, these may be primarily focused on tribal or family honor. Western societies consider such ill-defined local traditions and practices as retrograde and highly irrational or “primitive,” signifying the lack of acceptance of the rule of law. In the West, and more particularly in the US, we appeal at the highest level to the idea of human rights, derived not from traditional forms of judgement and punishment, but from an abstract notion of justice, believed to be objective and impartial—and for that reason the foundation of our elaborate national judicial systems with their constitutions, lists of fundamental rights and case law history to enhance and reinforce the notion of objectivity.

That is the theory. The cultural practice is a little different. When we look at how informed citizens interpret the meaning of the abstract idea of justice, we discover that it fluctuates between two extremes: fairness (including mercy) and retribution or appropriate punishment. The term judgement itself is ambiguous, since it can alternatively mean “reasoned evaluation” or “final decision,” which may even be arbitrary. In US culture, compared to the cultures of other developed nations, the balance between fairness and retribution tips more strongly in the direction of punishment, the strict application of the letter of the law. This cultural bias accounts for the astronomic levels of incarceration as well as the trend—unthinkable in most other cultures—of three strikes statutes for sentencing adopted in the past two decades by 26 states and even the federal judicial system.

Thus, law in the US serves the primary purpose of exacting punishment. The actions of the legal system are essentially punitive rather than preventive. This is a notion all potential mass killers will have integrated into their cultural psyche. But something more is needed to transfer this responsibility from the courts to the heroic individual. And this time it is provided not by the official institution, but by popular culture, and more particularly the movies and television—media that revel in removing law from the legislative assembly and the courtroom (dominated by politicians and lawyers) and placing it in the conscience of every individual willing to be a hero for justice.

We may trace it back to Captain Ahab’s quest for resolution through the killing of Moby Dick, a mission that went well beyond the economics of whale hunting and took place outside territorial waters. A whale is, after all, a commercial commodity, at least from the crew’s point of view. But this whale had a name and a history, like a person. Every student of literature knows that Moby Dick is not just a huge white whale, but “stands for something.” In other words, for Ahab, Moby Dick was as much a cultural concept as a living being. Most significantly, the whale defined a personal, irrational mission for Ahab, a mission requiring annihilation through his final heroic act. Ahab was a quintessential American hero whose self-realization could only occur through killing.

Guns don’t kill. People with guns don’t kill (most of the time), even when there are a lot of them, as in the United States today. Cultures that worship guns do kill. And cultures that conceive of killing as the ultimate form of justice kill repeatedly and on a grand scale.

Melville built into his heroic adventure story multiple levels of metaphysical irony that develop a brilliantly subtle commentary on both 19th century American culture and the human condition. That’s what great writers have the leisure to do. It isn’t what the movie industry has time for. Nothing has done more to shape this theme of individual heroism than 20th and now 21st century Hollywood culture. It has made a specialty of glamorizing action heroes as agents of human and implicitly divine justice, to the point of even parodying itself in Last Action Hero.

In the multitude of examples that keep appearing, there is no single model of the hero or his (or her) situation, but all converge with similar logic. Some heroes actually do think and fret before they act, but the message is clear: It’s the action that counts, usually with the modest goal of saving humanity. The range includes every type of action hero—from cartoon superheroes and military snipers to tough cops, brilliant scientists or even, as in the case of True Grit, a 14 year-old girl. They always have a legitimate mission to accomplish, typically not necessarily recognized by the other characters in the film, and they all achieve it against various forms of adversity. At the heart of every story is the notion of a valid mission that only the hero is fully aware, moved by and capable of acting on.

How different this is from the classics of literature. Homer offered us the Trojan War in the form of an absurd cause that produced spectacular scenes of death mixed with admirable heroism, but it was the gods and not the heroes who knew what they were doing. Men were generally clueless and the heroes themselves capable of being ridiculous. Odysseus was a hero in war who was constantly distracted from his final post-victory domestic mission. The delight of reading the Odyssey lies in the richness of the hero’s experiences that have nothing to do with his mission. This may be why Hollywood has never really known what to do with Homer, in spite of his reputation as a talented story-teller.

When Shakespeare highlighted what we the public were expected to see as the folly of Othello, as he was preparing to execute his wife, Desdemona, he put in the Moor’s mouth the speech beginning “it is the cause.”

“It is the cause, it is the cause, my soul,–

Let me not name it to you, you chaste stars!–

It is the cause. It is the cause, it is the cause, my soul,–

Let me not name it to you, you chaste stars!–

It is the cause. Yet I’ll not shed her blood;

Nor scar that whiter skin of hers than snow,

And smooth as monumental alabaster.

Yet she must die, else she’ll betray more men.”

Othello wasn’t a sanguinary killer; he had a precise mission. He believed in the standards of “objective justice” that he identified with his adopted European civilization. He saw himself as a minister of that justice, so committed to its fair application that he was willing to execute his beloved wife. For the discerning audience, Othello’s speech highlights the two contrasted meanings of “cause,” which can be understood as the trigger of an effect (the reason something happens) or a mission to be played out, such as the “cause of justice.”

Earlier this year, Fair Observer published an article I wrote on the paradoxical parallels to be drawn between Othello and the murderous action of Dylann Roof in the black Charleston church. Roof was, in a very explicit way, a man with a cause applying his own criteria of justice in the form of directly administered capital punishment. We know this because he spent time explaining his action to his victims. In the case of Harper-Mercer, the cause may or may not have been militant atheism of the sort encouraged publicly by Bill Maher, Richard Dawkins, the late Christopher Hitchens or Sam Harris. We may never know, but it seems likely that Harper-Mercer entertained some notion of “fulfilling a purpose” he believed in as a justification for his crime.

The belief that there is no problem that can’t be solved through resolute action as a result of personal conviction is encoded in American culture’s DNA. In an action-first culture, what is perceived as a cause (origin of the problem) ends up defining the cause. The cause then becomes the mission of eliminating the identified source of whatever evil haunts us—real or imaginary.

Nothing illustrates this better than US foreign policy, which increasingly tends to focus on a specific human target. In some cases, following the logic of Moby Dick, the cause will target a single individual called Saddam Hussein, Osama Bin Laden, Muammar Gaddafi, Bashar al-Assad, Patrice Lamumba, Fidel Castro or even Vladimir Putin. This creates the cultural illusion that eliminating that person will solve a wider problem. In more problematic cases, where no individual leader emerges, the target will be a group of people defined by their allegiance: the Taliban, the Islamic State or, the former Cold War bugbear, the communists.

The singular focus of the cause (mission)—the elimination of the individual(s) identified as the cause (origin)—involves believing, like Ahab or Othello, that the death of the targeted individual will eliminate the evil we seek to eradicate. For groups, it is best to identify the leader, but failing that, the idea of decimating or even liquidating the group may be entertained. “The only good Taliban is a dead Taliban” updates the traditional dictum attributed (erroneously) to General Sheridan. Killing isn’t always necessary. Deposing the identified tyrant is often considered an adequate solution, but killing is a far more definitive solution. Bin Laden was most probably assassinated in order to avoid the messiness of judicial proceedings. Focusing on an identifiable guilty party to be eliminated in a single gesture is also a convenient way of avoiding thinking about the possibility of multiple contributing causes.

Access to the hall of the gods

But the cultural story isn’t yet quite complete. Guns, yes. Actions over thought, of course. The heroic mission focused on punishing the guilty and eliminating the source of evil: check. There is one more key ingredient provided in abundance by contemporary US culture: the cult of celebrity and fame. As Eric Harris, one of the Columbine killers, stated in his journal: “It’s not about the guns. It’s about the television. The films. The fame. The revolution.” The two accomplices at Columbine were not only, in their eyes, carrying out a heroic mission for the sake of humanity, but were responding to a widely-felt need for the ultimate form of self-realization shared by many young Americans in today’s reality television culture: celebrity.

Oscar Wilde famously said: “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.” Transposed to contemporary American culture, it might be that “there is only one thing worse than being talked about by classmates, and that’s not being talked about on television.” For the two accomplices in the Columbine massacre, knowing their names and their acts would be remembered by future generations was more important than the prospect of living their lives in obscurity, even if they would no longer be there to bask in the sun of their celebrity.

Speaking of television, on Bill Maher’s Real Time the day after the Oregon shootings, Adam Gopnick opined: “Every country, every nation has some core irrationality that it seems unable to escape.” He identified the “irrational fixation with guns,” “the love of guns,” as if that was the only irrational feature of US culture. We would all like to believe that our culture is based on rational principles even when we accept that it occasionally deviates or, as Gopnick asserts, contains one “core irrationality.” Culture, however, is never purely rational. It creates its own framework for rationality, or what the public considers as “rational behavior.”

In the US, the love of guns coexists alongside the worship of money (Gordon Gekko style capitalistic greed) and the craving for celebrity. That already makes three humdingers in the realm of irrationality which, if Gopnick’s claim is true, may help to define American exceptionalism as the right not only to “think different” à la Steve Jobs, but to act different in as many ways as possible.

The media have already begun focusing on these two perennially newsworthy questions: Who was Chris Harper-Mercer, and how did he procure the weapons that allowed him to kill nine people on a quiet campus in Oregon?

In his defense, Gopnick may have been attempting to give some perspective on cultures by pointing out that all cultures possess at least one major foible and so we should be tolerant and understanding when evaluating them. This may have been a reaction to another segment of the same show, a dialogue between Maher and another of his guests, British evolutionary scientist Richard Dawkins, a militant atheist. Not having seen the complete episode of Real Time, I don’t know whether this discussion preceded or followed the Maher-Dawkins conversation where the two men lamented their common fate as unloved and misunderstood liberals unjustly accused of being “Islamophobe, a silly word that means nothing,” according to Maher. To prove how baseless the appellation was, they began mocking their critics who typically (in their eyes, naively) trouble themselves to explain to these two adepts of rational thought that “that’s their culture, you have to respect it.” Having uttered this manifestly misguided quote, Dawkins took a deep breath before following up with, “Well, to hell with their culture.” Maher didn’t miss a beat as he smiled broadly and exclaimed, “Well, there you go.”

And indeed there we go. A heroic mission has been defined. There’s a culture to send “to hell,” which could only be a metaphoric expression for such non-believers, but even so “to hell with” implies first giving up the ghost before reaching the final destination. One gets the sense that the death of all believers wouldn’t be an unwelcome solution for these two self-proclaimed true liberals, “a consummation devoutly to be wished.”

In fact, both men spend a lot of time and energy carrying out that mission, though with much more powerful weapons than the 13 guns Harper-Mercer possessed. They have a permanent platform on a range of richly endowed media. Maher and Dawkins are assertive and successful. They have achieved celebrity and share a well-defined mission accompanied by what they believe is a deep sense of justice. Thanks to their already acquired celebrity, they don’t need to kill their enemies—just incite other people to agree with the mission that ideally will end up snuffing them out. They may even be privately reassured by the fact that their respective governments—in Washington and London—have been doing it on a regular basis for the past 12 years.

2016 beckons

One last word on politics, since this is all taking place in the context of the buildup to the most surreal presidential primary season in US electoral history. The two leading Republican candidates have firmly endorsed protecting the rights of Americans to own and presumably use assault weapons. Here is Donald Trump: “The bad guys are going to have them anyway. What happens when the bad guys have the assault weapons and you don’t in a confrontation?”

Ben Carson, who is second to Trump in most of the polls for the Republican nomination, says that Americans must have access to assault rifles and “armor-penetrating ammunition” to defend themselves from “an overly aggressive government.”

Here are two clearly stated culturally shaped “visions” of society. In the first, good guys and bad guys circulate in the same environment fully armed, playing out a kind of persistent video game. The bad guys are looking to take advantage of the good guys, who have to stay on the qui vive and be ready to fire whenever one threatens. Justice will thus be served instantaneously. In the second, self-reliant citizens safely barricaded within their homes are enlisted by some tacit initiation process into a nationwide armed militia that will be ready to step into action on command to resist the tyranny of the elected government that at some point becomes “overly aggressive.”

Listening to such discourse spoken by these candidates with serious intent, one can only conclude that American politics, at least on the Republican side (and they still hold the legislative majority), has literally gone raving mad. It is nothing less than bonkers, unhinged, round the bend, whacko when it comes to talking about the idea of guns and their role in society.

That’s politics. Will the culture follow?

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

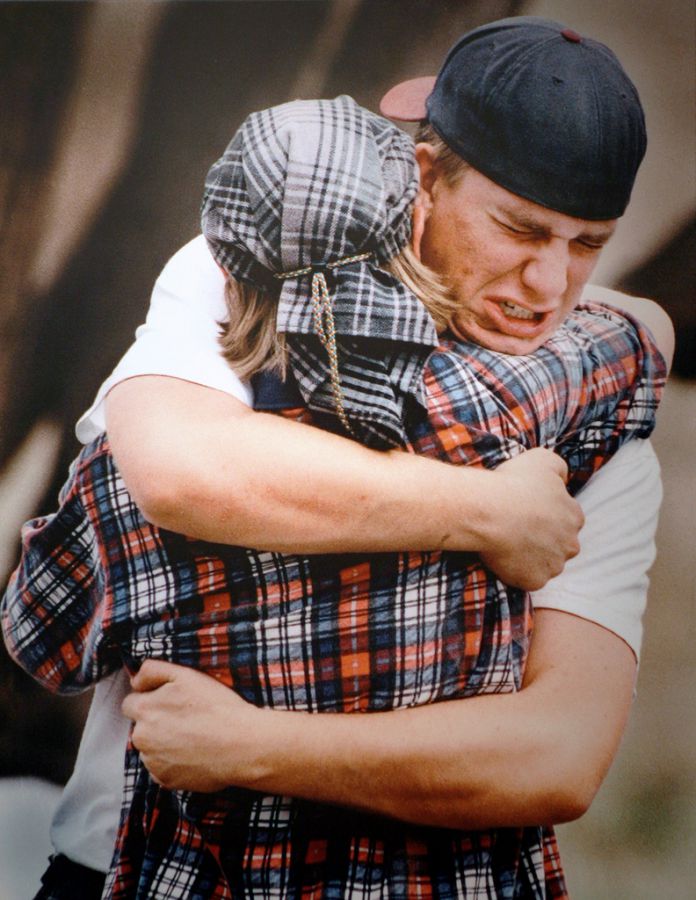

Photo Credit: Oconnelll / Shutterstock.com / Colombine / Cliff

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.