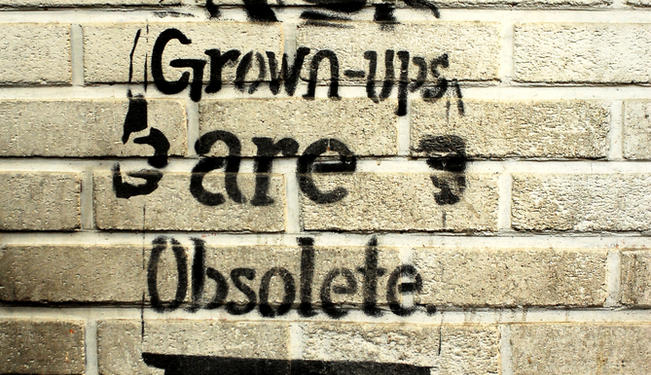

While street art is becoming increasingly more popular in the mainstream, artists still, more often than not, risk arrest and criminal charges, raising important questions about how we define and appreciate art. It is safe to say that all of us, at some point in our lives, have been exposed to street art. Lurking under bridges, spilling over billboards, splashing colour across grey concrete, derelict buildings and subway carts,the work of masked night warriors spans every city on every continent. To some, it brings joy. To others, it is mere vandalism. But with the recent explosion in street art’s popularity and its projection into the realm of critically acclaimed modern art, it is time to question its precarious existence between the gallery and the prison cell. The term graffiti comes from Greek for “writing”, and its Italian variant referred to the inscriptions found on Roman ruins. One could take a step back even further, and talk about cave paintings, tracing contemporary street art’s origins in human kind’s innate need for self-expression. Indeed, street art is often presented as a truly popular art form, in that is accessible to all, without elitist prejudice and price. The credo of the street artist is often that of a guerrilla – a fighter for creative freedom for all, a spray can held up in defiance of an oppressive system. Legally, street art is considered vandalism, because defacing public and private property without permission is a criminal offence. But last year, academics have called for legal protection for the work of the world’s most famous, or rather infamous, artist – Banksy, following a number of incidents of his work being accidentally painted over. A 2006 poll conducted by the University of Bristol found a 93% support to keep Banksy’s work. This new development has put a controversial twist on the question of what is considered art, or vandalism. Although street art, or rather graffiti, has been used throughout history to express political feelings and personal opinions in public, the first man to become famous for it was the Washington Heights resident Demetrius who, in the summer of 1969, was bored. Being a courier, he started leaving his signature TAKI 183 on buildings all over New York City, and in 1971 an article in the New York Times (NYT) made him famous, inspiring numerous copycats. As his website puts it, “The floodgates opened.” The appeal of this seemingly pointless stint is highlighted in the NYT article, in the words of Transit Authority patrolman Floyd Holoway, who said he “had caught teenagers [graffiting] from all parts of the city, all races and religions and all economic classes”. The art revolution was here to stay. Since then, street art has flowered into an elaborate de-centralised movement that incorporates styles such as traditional spray can paintings, stencils, mosaics, stickers, video installations and even flash mobs. From Keith Haring’s first subway drawings in the 1970s, inspired by William Burroughs and Andy Warhol to create a truly public art, Jean-Michel Basquait’s (SAMO) pithy graffiti messages, Mode2’s vivid, vast murals and hundreds more carefully documented by the photographer Martha Cooper, street art started making its way into galleries and legal public spaces. But it was with the appearance of the anonymous Bristol-born Banksy that the hype really went viral. In 2008, the famous London auction house Bonhams held its inaugural street art auction, and Tate Modern - the world’s biggest contemporary art museum - opened a street art show. Banksy’s Bombing Middle England sold for a record £ 102,000 at Sotherby’s in February 2007, only to fetch $1.8 mn at an AIDS charity auction organised by U2’s Bono and artist Damien Hirst the following year. In 2009, Shepard Fairey’s portrait of Barack Obama, which has arguably become one of the most-recognised images in the western world, was purchased by the National Portrait Gallery in Washington. His design consultancy clients include Nike and Birds Eye. The 2011 street art show in LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art attracted 20,000 visitors onits first day and Banksy’s mockumentary “Exit Through the Gift Shop”was nominated for an Oscar. On October 29, 2012, Bonhams opened its first LA auction. It appears that street art is beginning to shed its rebel’s cloak. Or is it? In 1971, New York was spending on average $300,000 a year on removing graffiti. In 2010, NoGraf Network President Randy Campbell estimated the yearly cost of monitoring, detecting and removing graffiti at $15-$18 bn a year. In London, a House of Lords committee estimated the damage at £100mn per year in 2003. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, graffiti is the most common type of vandalism. Shepard Fairey says he has been arrested at least 14 times. Artist Revok told a documentary dedicated to the MOCA show that he had spent around $70,000 combating vandalism charges. He was arrested for six months for failing to pay restitution while the show was still in progress. And whatever skeptics say about Banksy’s anonymity, legal issues might be part of it, still. Boundaries between street art and contemporary art are fast fading. This ephemeral phenomenon, alive mostly on film, refused to dissipate into the fog of oblivion and instead has pushed the boundaries of public acceptability. The distinction between vandalism and art is a subjective one, alas, making many street artists criminals to this day who use the money they make from their work to pay vandalism fines. But, as the artist Saber has put it, “They let us in. That was their biggest mistake.”

Image: Copyright © Neale Cousland (1 & 2), Rob Ahrens (3): Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.