by Kevin Kwok and Anna Pivorvarchuk.

As social mobility increases, nationalism and right-wing extremist groups worldwide are gaining popular support.

Background

Populism is defined as a political doctrine that represents the interests of ordinary people, especially in a struggle against a privileged elite. It is a potent political catalyst harnessed by leaders to increase their circles of influence by channeling the broad support of a society’s population, often by blurring people’s perceptions of their own interests with the interests of the nation-state they identify with. This fusion of populism and nationalism is behind the creation of many contemporary far right movements in Europe, in East Asia, and in the United States.

The term fenqing is used in China for the phenomenon of excessively nationalistic youth. They are easily riled up into participating in violent demonstrations, as the latest round of anti-Japan protests over the Diaoyu Islands have shown. Hong Kong nationalism takes on an existentialist bent: confusion over the territory’s identity and relationship with mainland China occasionally erupts into anti-mainland sentiment and colonial nostalgia, as anger over a proposed nationalist education reform in early September demonstrated.

In Japan, nationalism usually manifests itself in far-right activists responding to Chinese goading. However, unlike China and the Korean peninsula, Japanese strains of nationalism and far-right thought do not stem from a sense of national grievance, due to their recent history of being the region’s aggressors.

Europe’s right-wing extremism problem was hauled out of the shadows by Anders Behring Breivik’s shocking attack in July 2011 which killed 77 people. While many government agencies still hide behind the “lone wolves” theory, a 2012 Europol report concludes that the “threat of violent right-wing extremism has reached new levels in Europe and should not be underestimated”. Another report by the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism in the Hague adds that least 249 have been killed in far-right violence in Europe since 1990, compared with 263 victims of jihadist extremism.

In Germany, although the far right only won around 2% of the vote in the 2009 federal election, security services have documented a rise in the number of professed neo-Nazis to 10,000. In Britain, where the British National Party failed to defend any of its six seats and only gained the national average of 1.9%, the English Defense League – a counter-jihadist street movement with possibly as many as 35,000 supporters – remains widely active.

Europe’s far right parties have made significant election gains in the last few years. In France, Marine Le Pen’s National Front won 18% of first round votes in the presidential election this year, Greece’s Golden Dawn party won parliamentary seats for the first time, and Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party was third largest in the Netherlands until this month’s election. These parties exist Europe-wide and spout localised variations of rhetoric that is anti-immigration, eurosceptic and islamophobic.

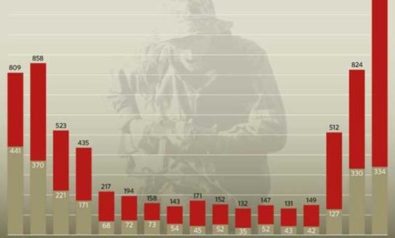

The United States has recently seen the success of the ultra-conservative Tea Party movement, with this year’s Republican presidential candidates catering to its agenda of anti-immigration, religious conservatism and distrust towards federal government. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, this so-called “Patriot” movement grew by 755% during the first three years of the Obama administration, and currently there are over 1,000 hate groups in the United States – a 69% increase from 2000. The 1999 Oklahoma City bombing, which killed 168 people and injured 800, was the biggest terrorist attack on US soil prior to 9/11 and a potent demonstration of American patriotism gone wrong.

Russia, having lost almost 30 million people in World War II, has seen a shocking resurgence of neo-Nazism targeting immigrants from the Caucasus and Central Asia. The US Department of State 2010 report estimated 150 nationalist groups in Russia, with the Russian Ministry of Interior putting the membership of “extremist youth groups” at around 200,000. The Moscow Human Rights Bureau documented 65 racist attacks in the first six months of 2012 alone, which resulted in 16 deaths and 91 wounded.

Why is the Issue Relevant?

Populism and nationalism can lead to inflammatory social consequences even if introduced apart from each other. In tandem, they can cause major disturbances within a country’s political and social sphere. Furthermore, there are suggestions that the global financial crisis has aggravated Europe’s xenophobic tendencies – Greece has seen a surge in hate crimes by Golden Dawn supporters. However, Greece’s 6.9% far right vote, although new, is around the European average, and Geert Wilders’s Freedom Party won 15 seats in the Dutch parliament despite Holland’s triple-A credit rating. The success of France’s National Front and Denmark’s People’s Party indicate a shift away from traditional far right racism towards a patriotic, “moderate” isolationism – a cultural defense of national values against the “otherness” of Islam, and the acceptance of this cultural racism into mainstream politics – a new far right.

The questions that need to be asked are whether widely-accepted government rhetoric about the failure of multiculturalism has created a favorable environment for nationalism and right-wing extremism, and also whether xenophobia is a tragic element of modern global society and a problem more fundamental than the current economic downturn.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All rights reserved.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.