It was 1963 when the governor of Alabama, George Wallace, proclaimed, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever … [in] the name of the greatest people that ever trod this earth,” referring to people with Western European ethnic ancestry. This and the ensuing pro-segregation forces in the US were very much a response to the 1954 Brown v. Board declaration that separate can never be equal, at least in public schools.

Amy Cooper, White Privilege and the Murder of Black People

The Supreme Court found this essential penumbra existed in the US Constitution — this soul of the document — and it was antithetical to “separate but equal” because education was the foundation of good citizenship. Obviously, the South had a soul that was different. Southern states famously defied segregation orders up to and following National Guard troop escorts of black students through color barriers throughout Alabama, Georgia and other states.

Years from now, future Americans will look back on the crucial period we are in similarly to the way we view the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s. The current pace of societal change, clashes over ideas that will dictate what societies look like and data left behind will all speak to what it was like to live in our time. Depending on the outcomes, how we emerge from coronavirus pandemic and how our systems react to people saying enough is enough when it comes to police brutality will shade how this period is perceived. Ultimately, now and then, there is an aspect, a connectivity to these two crucial issues (and others) that cannot be ignored.

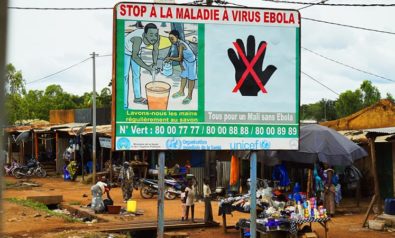

COVID-19

Take COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. For every 100,000 black Americans, 54.6 have died from the disease. That same figure is 24.9 deaths for Latinx Americans, 24.3 for Asian Americans and 22.7 for white Americans. We are talking about a difference of thousands of people. In fact, if people in every racial category died from COVID-19 at the same rate as white Americans, almost 13,000 black Americans and 1,300 Latino Americans would still be alive today, according to APM Research Lab.

We find similar statistics when looking at what happens when Americans interact with the police. White males aged 10 and over account for the largest number of deaths by the hands of police, yet black and Hispanic males are almost three and two times more likely to die from lethal police force, respectively. But surely, for many, this isn’t surprising.

In fact, both these sets of statistics may seem unsurprising, but what is more up for debate are the causes of these disparities. For COVID-19, we know that black Americans are at higher risk of exposure to the disease than white Americans. Predominately, black counties are seeing higher rates of infection (threefold) than predominantly white ones and a sixfold higher death rate largely due to the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease in these communities.

Comorbidities (additional diseases) may be driving deaths and sickness, but it is likely that overcrowding contributed greatly to the increased rate of infection. When the data is available, it is expected to be found that the cramped conditions in segregated communities like certain low-income areas of Chicago or areas with housing authority apartments in New York are to blame for such high COVID-19 rates amongst black populations. Lastly, it is clear that “essential” jobs during this current pandemic are overwhelmingly done by black and Latinx workers, putting them at a much greater risk.

The causal factors for the use of lethal force by police can be similarly laid out. Police encounters, from juvenile arrests to traffic stops and stop and frisk actions, are simply more likely to occur for blacks than whites, and to a lesser degree for Latinx Americans. Hence, this disparity exists whether or not the use of force was justified or not.

This finding matches what we know about the over-policing of communities of color. Commentators and researchers are quick to point out that there are factors like violence and petty crime incidence that likely contribute to this disparity. And while there are many confounding factors, similar to the comorbidities mentioned in regard to COVID-19, how big a role these factors play within and outside the context of race is a crucial question.

Disparity Beyond the “Comorbidities”

There is a video game known as “shoot don’t shoot.” It’s a very simple game that simulates decisions that can involve life-or-death scenarios. In the game, police officers hold a model gun (game controller), and on a screen complex, backgrounds like streets, hallways, campuses and apartments are displayed. A person is shown on the screen and the officer must decide whether or not to shoot based on if that person is armed or not. It’s simple.

Yet researchers have found that participants were more likely to shoot an armed or unarmed target if the person was black, and they were more likely not to shoot an unarmed or armed target quicker if the person was white. Simply put, participants needed less certainty to decide to shoot blacks than whites; this was true for all races of participants (including blacks) but worse for white participants.

Studies like these tell us that while there are various factors that put black men primarily at risk to these use-of-force encounters, there is an underlying bias at play. It is the same with COVID-19 and health care in America. We can talk about the poverty and income disparity all we want, but that does not explain why black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women in the United States. Most of these cases are the result of postpartum hemorrhaging, a completely preventable cause of death.

Data shows that income does not completely explain this disparity either. Infant mortality is more likely to devastate well-educated, middle-class black families more than poor white families with less than a high school education. This terrible outcome is tied to the interactions black patients have with health care staff. Biases cloud the care received, so much so that, controlling for age, insurance status, income and severity of condition, black patients receive fewer diagnostic tests and have fewer surgeries. Like in the cases of blacks encountering police, the comorbidities do not explain much of these disparities. It is bias, and it is important to know that.

A Proper Diagnosis

Why is it so important to pinpoint the causes of these disparities? Because the most basic factor, implicit bias, is far-reaching and much more poisonous than others. The reality is that while the historic and institutional racism that has plagued the United States has had damaging and ever-present effects, we have, can and will watch them heal. In the 1960s, we watched racist laws get repealed, and while it is easy to see that the overt racism of these laws often was transformed into the dog whistle-coded policies of Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and other US presidents, there is no shortage of movement to turn back the tides of theses hideous policies.

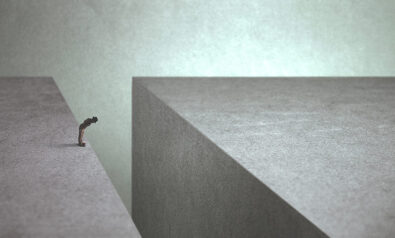

The current progressive movement focusing on the right to health care, housing, education and even a cushioning of the safety-net through the outright provision of income and jobs is astounding. Looking at this current political moment in the context of a longer arc of history, the policy priorities making their way through the body politic have the potential to undo decades of ruthless policymaking that left the average American behind — this includes black, Latinx and other minorities. So, if we are allowed a cautious slither of hope, one can say that that this moment in time may lead us into a future with much less income inequality and racial disparity.

However, if it feels too early to celebrate, it is. For the specter of implicit bias may remain, even in that rosy future. Let’s take a moment to understand how implicit bias really works. There is no better exhibition than that of a 2011 study in the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences journal. The study looked into the question of whether justice is blind and discovered, in fact, that justice was hungry. The authors went into courtrooms and observed judges. They recorded their activities, including their two daily food breaks. The two food breaks created three sets of decisions, those made before, in between and after both breaks. They found that the percentage of favorable rulings dropped from about 65% to almost zero within each period. Then, after each lunch break, favorable rulings abruptly jumped back up to about 65%.

This is how implicit bias works. It doesn’t announce itself. It doesn’t come with dog whistles. It affects everyone, but no one admits to it. Like judges who see themselves as the beacons of impartiality and would never admit that their grumbling stomachs weigh in on their decision, everyone from real estate agents and hiring departments to doctors and the police are often in denial about inherent biases. This is bad when it means unfair treatment of the defendant with unlucky timing, and it is devastating when it indicts entire races.

Solving Implicit Bias

In order to fix implicit bias, we have to face it, which may be more difficult than facing the racism of yesteryear. It is easy in today’s world to paint the American South as the stalwart of racial progress and symbol of racism. Documents like the 1956 Southern Manifesto, which 96 Democratic congressmen signed, perfectly display this. But seldom is it pointed out that the most segregated areas in the US today are in the North and the Midwest and have long surpassed the South in that category. This is due largely to implicit not explicit bias.

Segregation is important in the conversation about implicit bias because it is one of the most crucial steps between implicit bias and police killings, lack of access to health care and concentration of underhoused people. It is important to understand how the racial issues of today and tomorrow will not be that of the archetypal angry Southern racist(while that population may still exist), and its causes are not Ku Klux Klan violence, black codes or issues with incomes and wealth.

It is easier to talk about implicit bias, through a steppingstone like segregation because everyone can see it. In American schools, work places and neighborhoods, you can see it, and the stark realization that despite the fact that you don’t know anyone who is racist but you exist in a largely homogenous community is visceral. Though being able to clearly see the manifestation of implicit bias is only half the battle.

Psychologists know that implicit biases are often not congruent with the possessor’s conscious beliefs. For example, researchers have observed white men having increased levels of activity in parts of the brain needed to process threats when seeing a black face, and this heightened activity highly correlates with implicit bias. Studies have found that African Americans are given longer sentences than white defendants. The United States Sentencing Commission found that blacks received sentences 19.1% longer than similarly situated white male offenders.

The most popular solution rolled-out across the nation is addressing bias by raising awareness. The idea being that once a person knows they are affected by bias, they have control over it. The idea of awareness holds some theoretical veracity, but research has revealed that in some cases, the popular interventions to alter racial opinions can have minimal and sometimes an effect opposite of that which was intended. Simply telling people that biases exist is not enough.

Advances in neuroscience have allowed for the development of novel insights into the way the brain sorts, synthesizes and responds to massive influxes of stimuli. The preeminent theory on how the brain takes on this task is called predictive coding, a unified theory of brain function or the “hidden brain” as it has been referred to. The research is largely in its infancy, but the idea is that incoming data is synthesized via an interplay between the “slow-thinking” part (frontal lobe region) and the “fast-thinking” part (ex. amygdala). The brain has “codes” for patterns from the past that it probabilistically matches to the incoming data. This makes us really good at quickly recognizing things in our world but also subject to problematic conclusions. Implicit bias occurs because of this process functioning efficiently.

Theoretically, it happens because we quickly sort people into groups, based on past experience. We build up an unconscious empathy for some groups over others, using aspects like how much like ourselves a person is or on what society, experience and education have taught us. This empathy is dished out largely due to how we group individuals — that’s bias. Research has confirmed that the strongest of applications of this empathy comes when our brain believes something is similar or related to us, meaning that in high-tension environments, left unchecked, these outgroup biases are activated.

How do we fix what we cannot see or check what we do not even believe about ourselves? Rules, public policy and institutions large and small should be run as if everyone has implicit biases. While regular bias training and diversity initiatives have returned questionable results, there are some glimpses of hope.

Research actually shows that ownership of an outgroup body through the virtual reality (VR) experience can be used to reduce implicit bias. The user is tricked into another’s skin, allowing that unconscious empathy to be shared more equitably. There are already researchers at the nonprofit group EQUALITY LAB applying this technique in the real world, including to police officers themselves. However, this technology is largely limited to how realistic the simulation is, so the best results await the creation of powerful VR tech.

In the meantime, it seems that political diversity does have a positive effect on intermediate steps between implicit bias and racial disparities. One study found that in cities with large black populations, court fees and fines become major sources of revenue, but this relationship is severely reduced by having just one black person on the city council. Bringing up these types of bias-focused approaches does not mean we should not fight for lowering income inequality or holding police accountable for their actions. The point is not to lose sight of how race truly impacts American life.

Dealing With Bias

To be clear, the approaches to dealing with implicit bias may not be the best when confronting overt racism, and the more outward-facing bias still contributes to the disparities facing the United States. But while we do not seem to be suffering from a lack of awareness of racism, we seem to be falling into one of two camps: those ready to forget and ignore racism altogether and those wielding the word “racist” as a catch-all term.

It is important that we avoid falling too deep into the narrative that race-conscious politics can be forgotten in lieu of class-based politics, as Professor Adolph Reed Jr. seems to in his recent article, “Disparity Ideology, Coronavirus, and the Danger of the Return of Racial Medicine.” While it is true that we should not use race “as a proxy for the social conditions of poverty, lack of healthcare, and mass inequality,” it is just as true that giving everyone a health insurance card or $2,000 a month, and ensuring that police officers are punished for unlawful uses of force will not fix racial disparities in the US.

These are important goals, but they are detached from the problem of implicit bias. Similarly, we should be careful not to carelessly conflate institutional racism, implicit bias and overt racism as these are distinct and require different tools to mitigate.

Ultimately, thousands of people have hit the streets with the image of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin leaning his full weight behind a knee that dug into George Floyd’s neck as officers J. Alexander Kueng, Thomas Lane and Tou Thao stood by and watched. Many Americans cannot stop thinking about Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and the memories of the others before them.

The reality is that the same reason many black men fall at the hands of police weapons is the same reason thousands of black patients from cities around the US fall to COVID-19. We must deal with implicit bias and its steppingstone of segregation, or there will always be some degree of racial disparity. Every ounce of racial disparity is too much.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.