For the Aboriginal people of North America, sex was not associated with guilt.

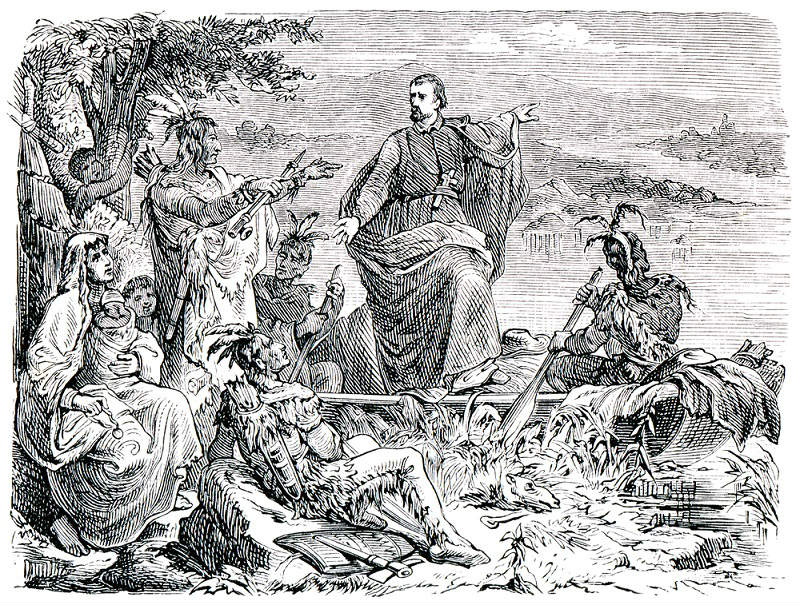

The Wendat (Huron) are an Aboriginal people whose descendants live in four communities across North America – in Quebec, Michigan, Kansas and Oklahoma – and separately across the continent. Their ancestors of the 17th century became well-known in Europe because of the writings of Jesuit missionaries who lived with them.

Obviously, a Catholic order of men sworn to celibacy might not seem the best source for talking about the sex life of an entire people, but the Jesuit drive for encyclopedic knowledge about their mission charges has made them a good source on this topic, nonetheless.

The Wendat formed a loose confederacy of four smaller nations or tribes: the Bear, Cord, Rock and Deer. They were a horticultural people, growing corn, beans and squash, which probably made up over two-thirds of their diet, the rest comprising fish, fruit and meat, fundamentally in that order. Most of the work of their horticulture — the planting, weeding, harvesting and grinding — was done by women. The most important social unit was the clan, a unit determined matrilineally. You belonged to the clan of your mother, not your father.

People who belonged to your clan were considered related to you. People of your own generation you would address as “brother” or “sister.” That meant it was considered incest to have sex with or marry them. In a detailed study of the 18th century Wyandot, one of the descendent groups of the Wendat and their linguistically and culturally closely related cousins, the Etionnontateronnon (people of where there is a mountain) – or Petun, as the French called them – there were no marriages between people of the same clan, despite the fact that they typically numbered between 500-600 people during the 18th century. To use a technical term, the people were still exogamous (i.e. marrying outside the clan).

A Woman’s Choice

Adultery happened (there was a Wendat term for it), but the person would have to be of a different clan. It must have been difficult to find the right place, as each house belonged to a particular clan, and could have between eight to 70 people sleeping there. The Wendat were a trading people, the men often canoeing a long distance to visit long established trading partners of other nations. They might have had marital partners there as well, as that would strengthen the social bonds between trading partners and nations. Early European recorders speak of such relationships in terms of a male perspective, not even considering that young women might have had decision-making authority in these matters. At the time, Aboriginal women generally had more say in mate-choosing — and disposing — than did their European sisters.

Wendat attitudes toward sex were certainly much more open and free than were the attitudes to which the French coming over to Canada (then called New France) were accustomed. Nothing recorded in writing illustrates this better than a sexual ceremony of the Wendat.

Brother Gabriel Sagard, a member of the Recollect order, not a Jesuit, observed during his stay with the Wendat in 1623-24 a significant healing ceremonial event in the culture:

“In the Huron country there are also assemblies of all the girls in a town at a sick woman’s couch, either at her request according to an imagination [vision] or dream she may have had, or by order of the Oki [shaman] for her health and recovery. When the girls are thus assembled they are all asked, one after another, which of the young men of the town they would like to sleep with them the next night. Each names one, and these are immediately notified by the masters of the ceremony and all come in the evening to sleep with those who have chosen them, in the presence of the sick woman, from one end of the lodge to the other, and they pass the whole night thus, while the two chiefs at the two ends of the house sing and rattle their tortoise-shells from evening till the following morning, when the ceremony is concluded.”

It is important to note that it was the young women that did the choosing, not the young men. This reflects the importance and respect given to women in Wendat culture.

“Be Enveloped in Sex For Me”

But Sagard did not speak of the name of this ceremony. The first one to do so was Jesuit Father Jerome Lalemant, writing in 1639. He wrote of an old man, Taorhenche, who was dying. He wished (through riddles that people had to guess) for a White Dog Ceremony, sufficient cornmeal to feed the people involved in the festivities, other unnamed ceremonies. At the end there was to be:

“The ceremony of the ‘andacwander,’ a mating of men with girls, which is made at the end of the feast. He specified that there should be 12 girls, and a thirteenth for himself.

“The answer being brought to the council, he was furnished immediately with what could be given at once, and this from the liberality and voluntary contributions of individuals who were present there and heard the matter mentioned, – these peoples glorying, on such occasions, in despoiling themselves of the most precious things they have. Afterward, the Captains went through the streets and public places, and through the cabins, announcing in a loud voice the desires of the sick man, and exhorting people to satisfy them promptly.

“They are not content to go on this errand once, – they repeat it three or four times, using such terms and accents that, indeed, one would think that the welfare of the whole country was at stake. Meanwhile, they take care to note the names of the girls and men who present themselves to carry out the principal desire of the sick man; and in the assembly of the feast these are named aloud, after which follow the congratulations of all those present, and the best pieces … then ensue the thanks of the sick man for the health that has been restored to him, professing himself entirely cured by this remedy.”

Unfortunately, the man was not cured in this context, but he died knowing he had the significant social support of his community.

The name of the ceremony was endakwandet, which literally means “they (indefinite) are enveloped in sex.” If you wished for the ceremony, you would say “tayendakwandeten” – be enveloped in sex for me. The Jesuit fought to suppress this custom. By 1649, when the Wendat were on the brink of being driven out of their traditional territory, the most Christian of the communities refused to hold this ceremony.

It speaks of several aspects of traditional Wendat culture. It seems to demonstrate that their publicly-articulated attitude toward sex was one that it was something to celebrate, not constrain. And it suggests that female sexuality was something thought natural, not something to be controlled. The Wendat language had no terms for “innocence” or “guilt,” so did not have those cultural concepts to condemn female sexuality.

This was an Aboriginal society at the time of first contact. This is before white male fur traders sought compliant women among the people; before gallons of alcohol were poured into the fur trade; before the Indian Act gave men power and took it away from women; before colonial oppression and poverty turned the Algonquian (language family) word “squaw” meaning “female” or “woman” took on the negative connotations of “cheap brown whore”; before residential schools taught Aboriginal peoples the meaning of sexual abuse.

More recently, Aboriginal women have been sexual targets for Canadian serial killers John Martin Crawford and Robert Pickton. They are the most likely women in Canada to be sexually assaulted, murdered and to disappear. Fortunately, women such as those who initiated Idle No More are fighting for a return to the respect traditionally received by Aboriginal women, a respect readily seen in the 17th century culture of the Wendat.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Photosani / Bocman1973 / Mark Baldwin / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment