What are the pros and cons of de-extinction?

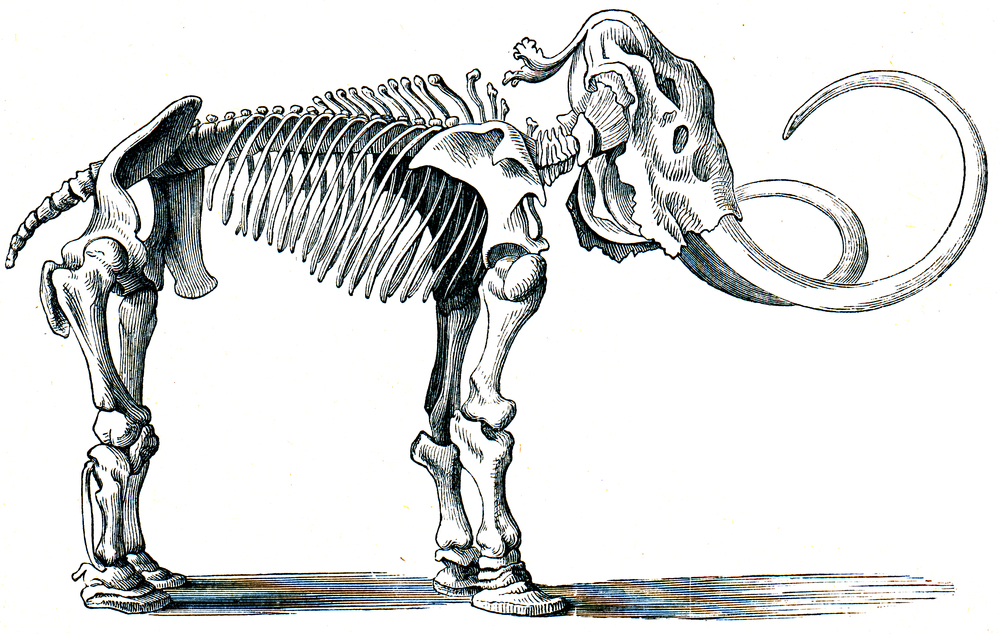

For many years, the icy tundra of northern Siberia has been hiding mysteries of glorious creatures that once walked the Earth. As you travel back in time to the Late Pleistocene age, visualize a magnificent mammal with 15-foot long tusks that intimidate those saber-tooth tigers and plough snow for food. This royal beast was covered in a coat of shaggy hair that grew up to a meter in length and helped it stay warm in one of the harshest places on the planet. Under this mass of hair and skin was a layer of fat as thick as ten centimeters to provide insulation against the unforgiving cold. A woolly mammoth was a walking fortress against the bitter Arctic winter.

In temperatures that hovered around minus 40 degrees Celsius for months on end, this majestic beast impeccably adapted to the extremes of the Arctic, and then, strangely plunged to extinction at the end of the last ice age. The woolly mammoth, or Mammuthus primigenius, was wiped off the surface of the earth not more than 4,000 years ago. These mammoths are among the most studied extinct species with well-preserved remains discovered in Siberia and Alaska, including tusks, dung, internal organs and depictions found in prehistoric cave paintings.

As global warming melts permafrost faster than ever before, the treasure trove of their remains is finally emerging, revealing a world of mysterious flora and fauna that thrived and evolved in difficult conditions. Science, through DNA mapping and cloning, is now revolutionizing what we understand of an extraordinary animal that roamed one of the most inhospitable and remote places on earth.

What if science can rescue this iconic and enigmatic titan and bring it back to the planet of the present? What if cloning this extraordinary species gave life a second chance? Will paleogenetics make it possible and sustainable? Will science ratiocinate its way around principles and ethics? The questions are many and necessary.

Paleogenetics

When a carcass of a female mammoth, dead for nearly 10,000-15,000 years, was found buried in an icy tomb in Siberia, we inched closer to the Jurassic Park fantasy. Scientists claimed to have discovered blood and muscle tissue in the remarkably preserved remains that may or may not contain a viable complete genome. Since the mammoths have been gone for thousands of years, causing DNA to degrade gradually, the possibility of finding an intact genome is highly rare.

As you travel back in time to the Late Pleistocene age, visualize a magnificent mammal with 15-foot long tusks that intimidate those saber-tooth tigers and plough snow for food. This royal beast was covered in a coat of shaggy hair that grew up to a meter in length and helped it stay warm in one of the harshest places on the planet.

In these circumstances, it is likely that paleogeneticists would extract only bits and pieces of genetic information from the mammoth. This would then be woven into a DNA fabric based on their best estimation of mammoth genome. The genome will be gradually planted into the embryo of a modern Asian elephant bit by bit, until the DNA in the elephant embryo is completely replaced with mammoth DNA. It would possibly be fair to say the mammoth might not be resurrected in its most accurate form, but of what science can churn out and believes it could be.

Pandora’s Box

Let’s face it: De-extinction is time, effort and a fund-intensive process. There are many endangered species that require our attention right here, right now. It seems absurd that instead of channeling resources and funds to tame the existing battle between human habitats and wildlife conservation, we would rather bring back the “favorites.” The resurrected mammoths will also be heavily conservation dependent. So, “Is resurrecting animals in a laboratory more crucial than safeguarding Earth’s prevalent biodiversity and ecological balance?” is a question we need to ask.

The roadblocks range from seemingly simple problems of difference in proteins of the mammoth embryo and the surrogate Asian elephant mother to the more complex ones, such as change in the geological makeup of Earth over the years. The combination of the mammoth and the modern Asian elephant will clearly not produce a pure mammoth. It is nearly impossible to get an exact replica considering we do not have a living mammoth to verify the behaviors and characteristics against. We could mostly hope to glimpse at a modern-day elephant with shaggy brown hair. Besides, the cloning, if successful, will only be the first step. The post-cloning progression on the mammoth’s habitat or diet would be the next major concern. While cloning is a huge undertaking in itself, reviving an entire population is another “mammoth” project in the waiting.

Since some prehistoric creatures were extinct long before they could evolve with time, we are now looking at animals like woolly mammoths that could perhaps adapt to the new world. But will the mammoth thrive or evolve in current conditions? Considering the dry and icy mammoth steppe of the ice age is long gone, the future survival of the revived woolly seems to be in jeopardy, especially since we are headed for a warmer planet. There has been serious debate on factors where artificially reintroducing mammoths into the natural ecosystem has been considered futile or even detrimental to the current ecological balance.

Stanley Temple, a founder of conservation biology, noted at the TEDx DeExtinction event that while we may favor one extinct exotic species over an endangered less fascinating one, we are creating a gap in biodiversity. While mammoths themselves might not pose a threat to other living organisms directly, it could be a vector for diseases, either dormant or new. Moreover, it would be unethical and unfair if an animal that has been extinct for thousands of years is brought back only to be kept in an experimental setting like a zoo.

Yet another argument that is making headway against de-extinction of these proboscideans is the possible nonchalance that would creep in, if we no longer feared extinction of endangered species.

There has been constant debate that by making the factor of extinction extinct itself, we may be indoctrinated to not worry about losing threatened species. After all, why lose sleep over loss of flora and fauna that can just as easily be recreated in a laboratory? We may be looking at further damage to the prevailing insufficient efforts to preservation of our biosphere. Revival projects with fascinating creatures are more than likely to draw attention that would, unfortunately, be unavailable for banal preservation efforts like protecting indigenous pollinators.

Extinction has been a fact of life for billions of years — and for a reason. Reintroducing woolly mammoths in the world of today may be invasive, even though they were around a few thousand years ago. It is easy to understand the thrill behind watching a lost species walk the Earth again. But history bears witness that when we toy with nature, there could be serious consequences that we often overlook.

Look at the cane toad nuisance, which arose after they were artificially deployed in Australia to counter cane beetles. While the beetles remained unthreatened, the poisonous cane toads grew in exponential numbers. It is now regarded as an invasive pest whose toxic skin kills other native animals and predators when ingested.

The issue with playing God in this case is that we may not know whether nature has already filled the gaps with other animals. It is also difficult to comprehend if existing species may be in peril by reappearance of mega-fauna that is long gone. It is for us to gauge whether this affects nature’s complex eco-balance system that could become susceptible to an adverse impact.

Reversing Time

But while the argument against reversing time and pursuing the holy grail of de-extinction is significant, science now brings us a chance to revolutionize our theories of the prehistoric Earth. The quest for de-extinction may now rescue the woolly mammoth that had long been locked away in a frozen grave.

On moral grounds, do we owe it to the animals that we have driven to extinction by indiscriminate hunting? Would you consider it justice for our beautiful fragile planet that we ravage to our own peril? Humans, as we are all aware, have been irresponsibly altering Earth’s biosphere in many ways, including causing extinction of entire populations of flora and fauna.

Although extinction is an essential part of biological evolution, human interference has accelerated the rate of extinction to more than 1,000 times. To offset this rapid collapse in our ecosystems, perhaps we have a responsibility to not only control the damage but possibly also reverse it. While climate change played a huge role in the extinction of the woolly mammoth, scientists believe that hunting by humans tipped the scales further against the mammoth’s battle for survival.

De-extinction of the woolly mammoth may also encourage ecological balance and diversity. Every living being contributes to the vast and complex web of ecosystem interdependence. Bringing back certain species may fix gaping holes in biodiversity. For example, the grazing habits of mammoths might spur an increase in forbs and carbon-fixing grass, which could in turn decelerate the melting rate of the Arctic permafrost. Understanding this is significant: If not controlled, the melting would release more greenhouse gases than burning all of Earth’s forests would.

Meanwhile, we are at the brink of groundbreaking exploration of valuable science. How specific genomes worked in an extinct animal, how different were they from their living relatives, what made them vulnerable, their role in evolution — the questions are many. The answers unearthed will pave new frontiers in conservation of endangered animals.

A near-extinct species with genetic mutation could be saved by altering and silencing bad genes through genetic variation and cloning. Moreover, scientists argue that while de-extinction is an expensive process, it is a useful science that would aid conservation.

For instance, stem cells taken for endangered species could be used for cloning to revive and grow their populations. In addition, since the process is fund-intensive, there would be added pressure to conserve environmental habitats that shelter these animals.

The Woolly Mammoth: Icons of Hope

Whether we agree or not, it is evident that de-extinction technology is here to stay. While the numerous pros and cons can be debated ceaselessly, it is still a case of “ifs and buts” until we witness a walking mammoth.

In the long-run, both arguments are viable and draw non-conclusive deductions. There will be unbounded legal and regulatory implications. There will be repercussions on biodiversity and territorial boundaries. The consequences of reversing time is too futuristic to be gauged.

It is essentially an abstruse and complex idea. In that sense, de-extinction is a stochastic science. However, de-extinction is inevitable. Our innate curiosity has propelled the question on resurrection to the next orbit — from “can we?” to “should we?” While some may view de-extinction as rearranging nature, some call it redemption. For now, it is still a wild vision. But in the near future, we may look at the woolly mammoth as a paladin of life’s hope over something as final as death.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment