Political infighting and violence have plagued Yemen since the Arab Spring began in December 2010.

The hopes and aspirations of Yemen’s youth have dissipated into a near permanent state of war. Five years on from the electrifying momentum toward change sweeping through the Arab world’s poorest nation, an entrenched stalemate has completely derailed the political transition process. The year-long civil war, now sponsored by an Arab coalition, feeds a regional war by proxy and serves as breeding grounds for the Islamic State (IS) and al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). The current situation has truly vaporized any sense of an Arab Spring, and instead has magnified a cycle of revenge among elite political actors.

The United Nations (UN), increasingly critical of the Saudi-led military coalition, has raised alarms over the devastating impact of the ongoing war. While armed clashes continue between Zaydi-Shia Houthi rebels, allied with military forces loyal to deposed President Ali Abdullah Saleh, and resistance militias, allied with military loyalists of President Abdo Rabbo Mansour Hadi, reports indicate that up to 93% of casualties and injuries from aerial bombardments have been civilians. The war has caused a collapse of the country’s health system throughout rebel- and resistance-held areas. Aid agencies have also reported that, as of August 2015, nearly 1.5 million people have been displaced by the current civil war. Prior to the conflict, there were 300,000 internally displaced persons. The Arab coalition also enforces an air and sea blockade, which is exacerbating the humanitarian crisis affecting over 80% of the population.

One year into the war, Houthi rebels and forces loyal to Saleh remain unaffected and committed to multiple fronts, some of which include clashes with militants affiliated with AQAP and affiliates of IS. Local media estimate that more than 160,000 airstrikes have taken place since March 2015 in Yemen by the Saudi-led coalition. Targets include military bases in northern Yemen, Houthi positions in multiple provinces, and houses of pro-Houthi leaders or associates, as well as the residence of former President Saleh and his relatives. Yet forces aligned with President Hadi have been unable to repel Houthis and Saleh’s forces from areas other than the coastal province of Aden. Fighting in Ibb, al-Jawf, Mareb and Taiz provinces remains intense and in constant flux. A number of ceasefires negotiated by UN Special Envoy Ismail Ould Cheikh have failed to deliver any relief since mid-2015.

Hope for opportunities to reengage peace talks among Yemeni actors, and the Arab coalition, remain faint as the option for total war appears to sustain the stubbornness on both sides. The recent appointment of General Ali Muhsin al-Ahmar as the new deputy chief of staff implies that Hadi and the Arab coalition are committed to a military victory. But Ali Muhsin’s resurrection since September 2014 may backfire and strengthen the Houthi-Saleh alliance rather than weaken their tribal pillars.

War crimes have undoubtedly been committed throughout the war, and reaching a lasting ceasefire long enough to engage peace talks remains a top priority amid growing fragmenting alliances. Reconstruction is simply beyond priorities held by warring parties at present.

Elite Bargaining

Debate over the nature of the political conflict that erupted in December 2010 has clearly eliminated the illusion of any populist movement, and provided overwhelming evidence of an intra-regime conflict responsible for today’s devastating war. The Arab Spring-inspired protests of 2011 across the Middle East and North Africa were all unique events, yet most observers fail to understand the origins and unique trajectory of Yemen’s own political infighting. It remains that an unresolved elite conflict perpetuates instability and is a principle reason for the breakdown of the transition process that was initiated in November 2011.

When Saleh stepped down after 33 years—the first phase of the transition plan—economically marginalized youth were neither empowered nor responsible for the autocrat’s downfall. The first indication of such marginalization was the fact that signatories to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) transition agreement only included the ruling party, the General People’s Congress (GPC), and the official opposition members of the Joint Meeting Parties (JMP).

In theory, the GCC-sponsored agreement negotiated by then-UN Special Envoy Jamal Benomar simply inked a temporary solution to a political crisis, which erupted in December 2010 when the GPC moved to unilaterally amend the constitution. Protests organized by would-be 2011 Nobel Laureate Tawakkol Karman and independent Member of Parliament (MP) Ahmed Saif Hashid coincided with the Tunisian uprising in December 2010. The situation escalated in Sanaa, the Yemeni capital, when the National Solidarity Council (NSC), led by Hussain Abdullah al-Ahmar, joined protests against Saleh’s move to reform the electoral commission and extend his term in office to make way for his oldest son, Ahmed Ali. Karman and Ahmar were seen as proxies for the Sunni Islamist party, al-Islah, which is the senior partner in the JMP.

The crisis leading to the Day of Rage, scheduled for February 3, 2011, was meant as political positioning rather than Saleh’s outright overthrow. The Islah party aimed at negotiating the parliamentary elections of April 2011, gaining further concessions from Saleh through a restructuring of economic resources and political posts, even if it meant marginalizing Sheikh Hamid Abdullah al-Ahmar’s ambitions to prevent Ahmed Ali’s ascent to the presidency in 2013.

Instead, the tsunami spreading from President Hosni Mubarak’s overthrow in Egypt emboldened Saleh’s principle rival, Sheikh Hamid, an MP for the Islah party. For Sheikh Hamid, there would be no negotiations on Ahmed Ali’s grasp on power. His support for the mass gatherings at Change Square undoubtedly represented a continuation of his fiery public criticism of Saleh since 2006. The stage was set for an escalation and the perfect storm gathered against Saleh—youth outside patronage networks, Sunni Islamists, Nasserists, socialists, Baathists, Houthis, GCC monarchies and even a US administration that believed time had come for democracy in the Arab world.

Failed reconciliation and backroom deals

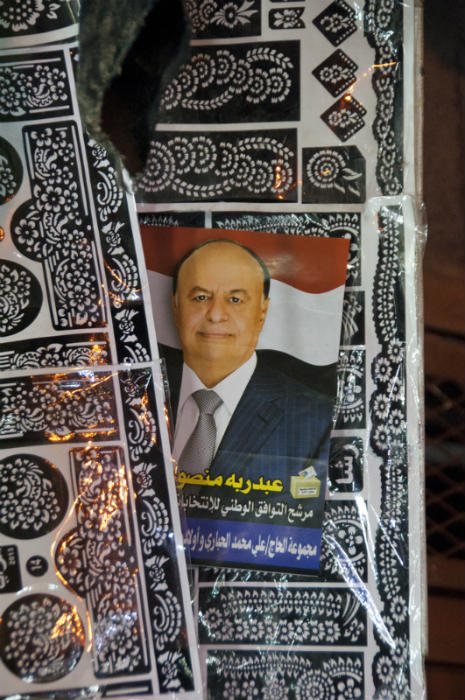

The second phase of the agreed-upon transition from Saleh’s rule involved the electoral ritual to elect Hadi as president. In a one-man election, under the mantra of consensus, Hadi was elected in February 2012. The process was mandated under the GCC agreement, which was meant to contain the crisis and avert a civil war rather than initiate an era of change.

Hadi served as Saleh’s vice president from 1994 to 2011, and while of southern origin, people saw him as a continuation of the regime. Another source of contention for independent protesters was the power sharing equation produced by the GCC deal, where half the cabinet posts were given to the GPC, half to the JMP with Islah taking the largest share, and the appointment of Mohammed Salem Basindwa as prime minister. Each faction picked the ministry appointees, while President Hadi was allowed to appoint the minister of defense; Basindwa was chosen as a nonpartisan candidate. No posts were reserved for independents or for representatives of marginalized youth protesting against the regime.

The hopes and aspirations of Yemen’s youth have dissipated into a near permanent state of war. Five years on from the electrifying momentum toward change sweeping through the Arab world’s poorest nation, an entrenched stalemate has completely derailed the political transition process.

This 35-member cabinet was to oversee the two-year transition period scheduled by the GCC. The first order of business was to restructure the national armed forces and security organizations, meant to gradually remove Saleh’s grip on vital national resources, but also targeted influence wielded by General Ali Muhsin, Saleh’s former close ally who defected in March 2011 and pledged to protect the “revolution.” The ultimate goal was to reform the armed forces in order to expand Hadi’s authority as commander in chief. The process not only bred further conflict among the elite, but eventually fragmented the military along patronage networks and further eroded President Hadi’s own power, rendering him nearly incapable of mobilizing sufficient resources to address the expanding security vacuum.

Breakdown of Dialogue

The third phase of the transition plan was the launching of a National Dialogue Conference (NDC). Delayed by a year, the NDC was finally established in March 2013. Again, ordinary Yemenis expressed their dissatisfaction with the equation used to select delegates, and later complained of further marginalization within negotiations by President Hadi, Jamal Benomar and the political elite, who bargained away aspirations of independents behind closed doors in order to produce a final agreement. Youth voices, in particular, were merely relegated to the occasional photo-op with the UN envoy and other diplomats.

The dialogue process began to disintegrate soon after Ramadan 2013, when war broke out in Amran province between Houthi rebels and tribes loyal to Sheikh Hamid al-Ahmar, and it quickly spread into Damaj, Sadah. This has been presented as the start of the transition’s failure. The war in Amran also led to a boycott by NDC southern delegates aligned with Mohammed Ali Ahmed, who was initially allied with President Hadi to represent the southern contingent along with Yassin Makawi and then-NDC Secretary-General Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak, who is now the Yemeni ambassador to the United States.

While a number of observers have fixated their analysis on the January 2015 Houthi-led coup, a trajectory of events identifies the Amran conflict as the start of both a historic realignment of the structure of power in northern Yemen, and the chaos that would ensue from August 2014. When the NDC concluded in January 2014, it further exacerbated the conflict as protests erupted from the GPC, Houthis and independents. Although it had been discussed in committees, the newly announced plan to establish a six-region federal state in Yemen intensified tensions among political parties, as it had not been part of the official NDC outcomes, but rather a plan forged behind closed doors and sponsored by President Hadi.

The Cause

Based on this author’s conversations with people inside the country, Yemeni analysts see the failure of Hadi’s government to contain the lingering elite conflict as being responsible for events that followed the NDC conclusion up until the Houthi takeover of Amran province. Houthi militia managed to capture Amran province from the 310th Brigade under General Hamid al-Qushaybi, a staunch ally of General Ali Muhsin and the Islah party. Islah officials were enraged at Hadi’s second failure to aid their cohorts—the war in Damaj was the first instance. Ali Muhsin, who also attempted to safeguard his position vis-à-vis Hadi, was attacked publicly by the party for his failure to deploy forces to Amran.

As events were mismanaged and the Hadi government overwhelmed, the government itself may have sealed its own fate and directly paved the way for a Houthi ascendency.

In July 2014, Prime Minister Basindwa’s cabinet agreed to lift fuel subsidies, handing Houthi rebels the opportunity to revive their revolutionary narrative on behalf of the masses. Houthis undoubtedly capitalized on the anger among Yemenis and reclaimed the banner of revolution from 2011. Thousands across the political spectrum answered the call to demonstrate, including GPC loyalists, who organized social media campaigns and neighborhood protests often blocking streets around Sanaa. It was an opportunity to capitalize on renewed popular discontent that neither Houthis nor Saleh could waste. A new alliance between former enemies was forged in the oddest revolutionary narratives.

Bleak prospects beyond the stalemate

The stage was set for a final blow on the “model transition” and a downward spin into chaos. Hadi’s position was in peril, as early reports indicated that Houthis and Saleh forged their alliance of convenience outside Yemen with help from regional powers.

Events leading to a Houthi takeover of the Yemeni capital in September 2014 were a product of overconfidence on the part of President Hadi, and Houthi collusion with Saleh’s military and tribal loyalists. Hadi is said to have opened the gates of Sanaa for Houthis in efforts to shift the balance of power away from General Ali Muhsin and the Islah party. But President Hadi, Benomar and bin Mubarak were unaware of the Houthi-Saleh alliance that ensured a military defeat of Ali Muhsin and the political downfall of Islah.

Hadi was forced to accept Houthi interpretation of the Peace and National Partnership Agreement (PNPA) signed on September 22, 2014, including a new power sharing equation abrogating the entire text of the GCC initiative, especially since the president had originally been granted only a two-year term. Houthis were not signatories to the GCC agreement, therefore, the PNAP gave the rebels a seat at the table otherwise not granted by the NDC.

The period between Houthi calls to protest against the lifting of fuel subsidies and the coup d’état of January 2015 undoubtedly took President Hadi by surprise, along with the international community. It is clear the transition was mismanaged, and that regional and international powers underestimated a number of political actors, such as the Islah party, Ali Muhsin, Saleh and Houthis.

This view is indeed Sanaa-centric, and does neglect the role of southern secessionists, but this group remained on the sidelines of the northern power struggle until President Hadi fled house arrest and landed in Aden in February 2015. The relevance of southern actors has surged as Yemen faces a historic possibility of fragmentation. At this time, underestimating political actors, especially Saleh’s survival, left the international community unable to deal with strong challenges to Hadi’s legitimacy, leaving only the use of force as an option against Houthis and Saleh over the past year.

Today, the situation in Yemen is far beyond a “crossroads.” It is beyond “the brink.” The conflict faces a dangerous impasse as low intensity clashes expand, exacerbating the humanitarian crisis and widening the security vacuum across the country. It is no longer a conflict between traditional elite actors, as southern and northern Salafists have joined the fight against Houthis and Saleh’s loyalists. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula no longer holds a monopoly on Yemen as Islamic State-affiliates have established a presence in various provinces. This makes it even more difficult to coordinate peace talks.

Furthermore, President Hadi has been unable to sustain support from various resistance groups fighting Houthis, as tension rises over financial and material resources provided by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The Saudis hope that General Ali Muhsin can serve as a uniting figure among northern tribes in order to overcome current obstacles along the military front.

After one year of airstrikes on the capital Sanaa, Amran, Hajja and Sadah provinces, observers see a deepening quagmire for Saudi Arabia, at times using the Vietnam analogy. It is clear that no actor is in a position to make concessions. There is no confidence among warring parties due to weak, fragmented alliances, and UN efforts are hindered by a lack of resources.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Claudiovidri / Peter Sobolev / Dinosmichail / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.