The future of Turkey hangs in the balance, and society is more polarized than it has ever been under the AKP.

Since the general election of June 2015, which led to a hung parliament, Turkey has found itself embroiled in three instances of terrorism. In each case, the disproportionate victims have been Kurdish in origin. The Diyarbakir bombing in early June killed four people. The Suruc bombing in July took 33 lives. The Ankara bombing on October 10, in the nation’s capital city, killed at least 128 mostly young people. The last tragedy happened just three weeks before another general election on November 1, where the outcome is likely to remain the same as it was in June.

It is still unclear who is behind these terrorist attacks or what it all means for the immediate future of Turkey, although considerable focus has pointed toward the Islamic State (IS).

Many observers and critics have blamed IS for the Ankara bombings which, for some others, implicates the current Turkish government. There is a certain body of Turks who regard the Justice and Development Party (AKP) as wholly sympathetic to IS. Many believe that any IS action could not have happened without state approval. It is a speculative notion, but nevertheless a popular one among a significant section of the population.

For this particular group, the current government represents totalitarianism, corruption and myopia. There is certainly a great deal of plausibility behind such a theoretical perspective. On the other hand, it begs the question of whether a government is prepared to annihilate its own citizens for the purposes of remaining in power, however unpopular governments might be.

All the same, the idea of a “deep state” is not new to Turkey. During the Cold War, the power of the military and its ideological position, shaped by Kemalism, were the driving forces behind three significant coups. Periodically, the Turkish military apparatus has taken authority of the country into its own hands. Undeniably, as we have witnessed elsewhere, the idea of a “deep state” working in the interests of the military is not so unpalatable for others in the Middle East.

Conversely, there are others who suggest that while there may or may not have been collusion between the AKP and the Islamic State in the past, Turkey’s recent entry into the theater of war in Syria and Iraq may well have generated a deep fissure between these two forces of will and might. It leads to the popular view that IS was behind the recent attacks in Ankara.

Another viewpoint focuses on the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Kurds. The argument here is that the stance of the PKK, while generally supporting the notion of a peace process and a long-term ceasefire to permit a resolution to evolve, may not entirely chime with the wider discourse of the group. It is suggested that elements of the PKK want to stir up the basis for perpetual conflict. They do not believe there can ever be a solution unless there is complete recognition, status and final acceptance of an independent Turkish Kurdistan.

A final outlook focuses on external actors whose aim to further destabilize Turkey, creating conditions for the nation to react without due care for long-term implications. The motivations of these actors result in buttressing their own claims to authority in the region. Fingers have been pointed at Israel and Iran. While popular among a certain urban class of Turks, these theories seemingly legitimize the idea that Turkey must stand up to external aggressors whose wish is to manufacture the seeds for the destruction of their great nation, thereby retaining post-Kemalist notions of national security.

Polarized Society

While speculations abound, many people have lost their lives in these few months and considerable periods before. Political violence, terrorism and social unrest are not new to Turkey, as the recent Gezi Park events of 2013 demonstrated. The fact of the matter is that Turkey remains a deeply polarized society, with stark differences between secular and conservative political and ideological orientations, as well as deep religious and cultural schisms between liberals and those of a more religious orientation.

These relations are further compounded by the center-periphery dynamic that has historically produced class, race and religious differences associated directly with the means of ownership of production, distribution and exchange, and the accumulation of physical, social and cultural capital in the hands of elite urbanites. While historically these elites were secular and Kemalist in origin, there has been a shift to the conservative and religious groups dominating not just aspects of the economy, but also media and politics in general.

As the race continues for economic, political and cultural stability, there is one group, representing approximately one-fifth of the population, which continues to suffer disproportionately. The Kurds have the most to gain and most to lose from the peace process and the current opening up of Turkish society that occurred since the end of the Cold War and the emergence of Turkey from a financial crisis at the end of the 20th century to the present.

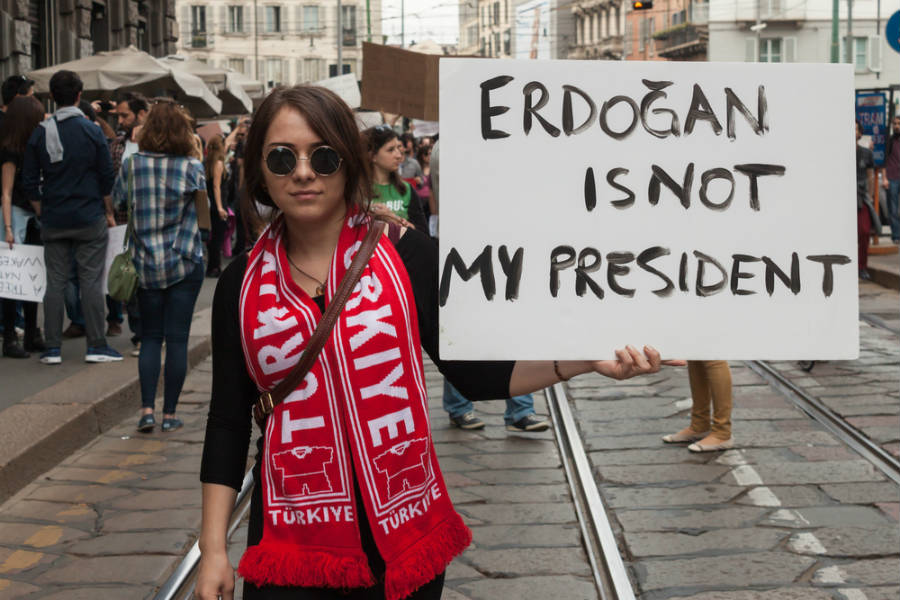

As to the wider Turkey, there is every reason to believe that the outcome of the November elections is unlikely to change significantly. All eyes will then return to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Since 2013, it has seemed that the authoritarian and neoliberal economic policies of the AKP have begun to foment discord among the population.

During this time, Erdogan has been viewed as the main villain of the piece. But now, everything depends on what he does next after the election. The whole of Turkey and the Middle East will be watching with bated breath amid an air of foreboding.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Thomas Koch / Stefano Tinti / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.