Reza J takes a closer look at some of the unknown aspects of the upcoming Iranian presidential election and examines Facebook as an instrument of dissent.

Forget all you have heard so far about Iran’s presidential election. Analysts are discussing the disqualification of Hashemi Rafsanjani and Esfandiar Mashaei, the most prestigious candidates from the reformist and Ahmadinejad camps. Others are arguing about the role of the Iranian supreme leader and the pre-selection of candidates by the Guardian Council. What is always forgotten about Iran’s presidential elections, however, are the vast numbers of unknown people who register for the race but never participate in the vote.

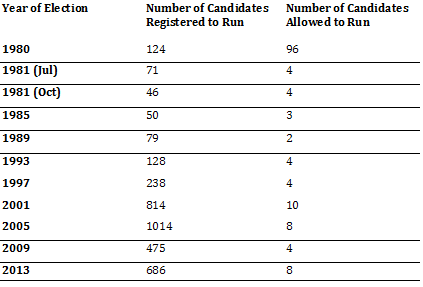

During the registration period, which recently ended, 686 candidates registered for Iran’s eleventh presidential election. The youngest person who registered was 19-years-old and the oldest was 87-years-old; 116 of them only had a high school diploma; 60 had not even finished high school; and 55 were students or unemployed.

Bizarre Candidates

This is not a new story in Iran. Almost the same play goes on before every presidential election in the country. Eight years ago, those who were in the Interior Ministry’s building during the registration period can remember the day that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad appeared to register as a candidate. After registering, he decided to talk to journalists but the microphone was too high for him, thus creating a humiliating situation for the person who later became the president of Iran.

These episodes are not the only humorous occasions of the five-day registration period. Many Iranian journalists and photo journalists go to the Interior Ministry to interview and take photos of bizarre and unknown registrants entering the highly secured building.

Among this year’s candidates were a football cheerleader; a candidate who went to the Interior Ministry in slippers; a candidate with a Panama hat and sunglasses; a young boy who was singing rap lyrics as his campaign slogan; 30 women (based on election law women cannot become president); an unknown candidate who said one night he dreamt that he must join the race; a candidate with his handwritten plan for the country; and an old man in shroud, holding an Iranian flag in one hand and a Qur'an in the other. Some candidates appeared in ties: after the revolution, the wearing of ties has always been seen as a symbol of the monarchy and Western culture.

The third day of registration started with a 32-year-old, Mohammad-Ali Farsi, who said that he was the ultimate savior of humankind and the final of the Twelve Imams. Another candidate arrived riding in a phaeton, an open horse carriage. Among all of them, the cheerleader grasped the most media attention and his interview was uploaded on YouTube — a website that is filtered inside Iran. In that interview, he said: “The president must be handsome, the president must be good-looking, the president must be well-shaped.”

What happened to all these people? Nothing special, the Guardian Council disqualified 678 of them. Based on Iran’s Presidential Election Law, six qualifications are required for presidential candidates. These are “being…religious and political Rijal (men),” “being of Iranian origin,” “being an Iranian subject,” “having the ability of management and leadership,” “having a good reputation, trustworthiness and piety”, and “being faithful and a believer in the foundations of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the official religion of the country.”

These six qualifications are ambiguous. The first one that says the candidate must be a religious and political “Rijal” is a good example. In Arabic, Rijal is the plural form for “Rajol” which means “man.” However, in Farsi, the word does not have the exact same meaning and it is possible to interpret it as a “well known person.” Because of this ambiguity, in 1997, for the first time a woman registered her name for candidacy. Nevertheless, this year a member of the Guardian Council clearly insisted that women could not be presidential candidates.

Moreover, one has to question how the Guardian Council can decide if a candidate has management ability or not. For instance, on May 21, the council decided that Hashemi Rafsanjani, who served as president of Iran from 1989 to 1997, does not possess management skills because he is 78-years-old. The presidential election law does, however, not prescribe any age limitation for presidential candidates.

Some people in the government assess the easy process of registering for candidacy as a notion of democracy. Despite this extremely easy way, the Guardian Council makes it almost impossible for most registrants to be an actual candidate. For example, in 2005, there were 1,014 people who thought they had these qualifications but the Guardian Council only allowed eight of them to enter the campaign.

Changes Over Time

The first presidential election in Iran in 1980 had the highest number of people who were allowed to join the contest. This can be explained by the initial freedom after the revolution when political parties were still allowed and political organization was free. After June 1981, when Ayatollah Khomeini dismissed Iran’s first president, political parties became illegal and the government imprisoned political activists, while the number of candidates who registered for candidacy dropped. In 2001, another major rise in the number of candidates occurred. The main reason for this increase was the strong presence of reformists in the political scene.

The year 2001 marked the start of reformist President Mohammad Khatami’s second term in office. Some analysts believe in that year conservatives tried to show the insignificance of the president’s position. To reach this goal, Iranian state TV covered the unknown and strange candidates in the Interior Ministry’s building. The unknown candidates have come into the spotlight again since 2001 in order to underline the president’s inferior position to the supreme leader.

According to Iran’s Presidential Election Law, everyone can register for the election. Most of the registrants know they do not have any chance to pass the vetting process, but go to the Interior Ministry just for the journalists’ cameras and microphones. They just want a closer seat for watching the show and to also tell their neighbors, colleagues, family and friends that they registered for the contest. In Farsi, important incidents like an election are called “the masters’ game.” These unknown people can enter the masters’ game by registering for the election; though their presence in the game only lasts until the result of the vetting process is released by the Guardian Council.

Facebook as an Instrument of Dissent

This anarchy in the registration process for the presidential election has also led to satirical Facebook pages. Even before the disputed presidential election in 2009, many Iranians believed that elections in the country were not free. This belief was due to the Guardian Council’s power to exclude any person from the race who was not aligned with their ideas.

However, for those who are trusted by the government, different campaigns start even before they register for the election. During the last two months, that exact phenomenon occurred, as many different organizations and political institutions began campaigns to invite famous political figures to enter the contest. Because of these early campaigns and the presence of more than 600 registrants for the election, many Facebook pages satirize the election. One of these pages is named: “The Campaign to Invite the Supreme Leader to Register for the Presidential Election.” The page’s wall photo shows three former presidents of Iran sitting close to the supreme leader, while a red-colored title reads: “Whom better than he, himself?” The page was launched on May 9, 2013 and one of its first posts states: “After 24 years of disobedience from clear orders of the supreme leader, it is the time for this liable great person to have both titles together.”

The supreme leader is not the only person who has a page mocking him. One of the most popular puppet characters from a TV series for children has a similar one. On the webpage, fake photos are uploaded that show Lionel Messi wearing a t-shirt with the character’s picture, the puppet meeting Khatami, Iran’s former president, and a picture of the puppet on the front page of international newspapers and on TV news channels.

Making fun of politicians is an old tradition in Iran and some great poets and writers like Ubayd Zakani wrote ironic pieces about them. The satire magazines with political content are one of the bestsellers in Iran, both before and after the revolution. But they have always been limited due to very strict censorship rules. They could never write about the shah or the supreme leader and they could not question the accuracy of election results.

Increased Polarization

After Iran’s last presidential election in 2009 and the subsequent uprising, the government’s popularity further decreased, even among those who still had some faith in the country’s Islamic leaders. Even many religious people started to question the fairness of the election. Consequently, Iranian society became polarized: one can only be with or against the government, there is no other intermediary position.

In February 2011, when the regime put two leaders of the Green Movement under house arrest, a new era of increased polarization began in the country. This was owed to the fact that the Green Movement’s leaders were among those who have shaped the Islamic Republic of Iran; they were not from outside the government circle. As a result, openly criticizing the supreme leader and other high-ranking politicians became more frequent.

However, the increased criticism against the regime in light of the 2009 elections is not the only reason for such satirical Facebook pages, because inside Iranian society, the Islamic leaders have always faced a crisis of legitimacy. Even during the first few years after the revolution, when the Islamists were still enjoying the majority support of the population, they faced a hard time cracking down on the extensive leftist movement. Shortly after the revolution, controlling the media was easier. After banning newspapers and taking control of the state TV channels, no other way was left for people to publicly voice their objections.

Today, however, with the expansion of social networks, recognizing this deep crisis inside Iran is clearer. The Internet and satellite TV channels are making political dissent more and more visible.

[Note: The author of this article wishes to remain anonymous and has used a pseudonym.]

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment