Landon Shroder provides a round-up of where 2015 finished and what 2016 might look like in the Middle East.

There have not been many epochs in recent memory that come close to the confusion, complexity and chaos that have defined the modern Middle East in 2015.

In the past year alone, we have seen an acceleration of the conflict with the Islamic State (IS) on multiple fronts in Iraq, Syria, France, Tunisia, Turkey and Lebanon, among others; the largest refugee migration since World War II; Russian military intervention in Syria; more US boots on the ground inside Iraq; a brutal war in Yemen being led by Saudi Arabia; a potential unity government in Libya; and, of course, there was the signing of a landmark nuclear deal with Iran.

Did I forget something?

Almost assuredly so, however, it is time to have a look at what 2016 might have in store for the Middle East. Are we expecting more of the same? Or will 2016 be the pinnacle year by which the endemic cycle of violence is finally broken in favor of pragmatic political solutions that might accommodate the complex challenges of a region in crisis?

That might be a tad bit optimistic, but let’s evaluate where the Middle East is taking us from the view of some key players in the region, and what might happen from a national and international perspective.

This is all deliciously complex, so please bear with me.

The Islamic State of Hysteria

The Islamic State has suffered some serious upsets in 2015, which have included an aerial campaign gratis of France, the US, Jordan, Britain, Russia, Canada, Turkey and even the United Arab Emirates. There have also been some battlefield successes in Iraq that have chipped away at the territorial integrity of the group’s so-called caliphate in places like Tikrit, Baiji and now Ramadi.

Nevertheless, IS must be defeated on four military fronts for any victory to be sustainable: as a conventional combat force; as a terrorist network; as an insurgent movement; and, most importantly, as a political and religious ideology. And so far, we have only managed to succeed in targeting the organization as a conventional combat force, which means we are no closer to defeating IS now than we were in July 2014, when the group broke out of Mosul.

The entire IS equation, however, is by no means balanced by military intervention alone. We often overlook the fact that the Islamic State’s successes are not just attributable to military prowess or religious fanaticism—although they play a part—but are also the result of political failures that gave agency to its cause in the first place, especially in Iraq and Syria. Therefore, political solutions must run congruent to any military operation for there to be long-term success in defeating IS. Unfortunately, at the end of 2015, these political solutions remain in short supply by the regional and international powers.

The good news is that in 2015, the IS caliphate finally hit the limit of its territorial expansion. And the group will continue to lose ground next year given the overwhelming international response aligning against it. The recently released audio message of IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, rallying his troops and supporters, underscores the fact that the Islamic State is feeling the pressure.

But as IS suffers more battlefield losses in Iraq and Syria, it will inevitably look to make up that deficit by engaging in acts of global terrorism. We have already seen the direct result of this in France, Turkey, Egypt, Lebanon and Tunisia, and in 2016, we should expect to see more terrorist attacks that can be attributed to IS.

Iraq’s Forever War

We certainly cannot talk about the Middle East without talking about Iraq, since the Islamic State was born in the chaos of US occupation and because former Iraqi army officers populate the upper echelon of the group’s military leadership.

In any case, Iraq is not faring well and 2016 will prove just as challenging. The precipitous drop in the price of oil has ravaged Iraq’s hydrocarbon-based economy, which will go into deficit only to be saved by loans from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank—contingent on governmental reforms that might not necessarily be deliverable. Coupled against ongoing military expenditure that has not been balanced in the war against IS, and Iraq has a pending economic crisis that could undermine the entire war effort.

While there has been some progress made in reclaiming territory from IS, what has become clear over the past year is that seizing territory in Iraq is not the same as holding territory in Iraq. The preeminent anti-IS fighting force has now become the Popular Mobilization Units (PMU), also known as the Hashed al-Shabi, and it comprises the various Shia militias with names such as the Badr Organization, League of the Righteous and Kitab Hezbollah.

For a lot of Sunnis, the fear of these militias and their history of sectarian violence far outweighs their fear of IS, making long-term political reconciliation in Iraq extremely difficult. This provides a strategic and tactical disadvantage for the Iraqi government, since the militias cannot hold or be garrisoned on Sunni land (long-term) due to the potential for sectarian reprisals. And without a process to reabsorb former IS territories back into the political orbit of the Iraqi government or national legislation to govern how the PMU operate, these areas will remain susceptible to terrorism and other forms of insurgency. Regardless of what happens on the battlefield, this will give IS an open corridor to maintain influence in Iraq for 2016.

Disclaimer: The United States

I must now offer you a disclaimer, because I have to break up our section on US foreign policy into two distinct parts: What is left of the Obama administration, and what foreign policy plans are being advanced by the various presidential candidates, because these two things are uniquely linked. With regard to the latter, be happy that there are only 11 more months of campaigning left, since we have not even remotely scraped the bottom of the proverbial foreign policy barrel just yet.

President Obama’s Foreign Policy Gambit

US foreign policy in 2015 was of mixed success, and it is unlikely that Washington will augment its current strategy for the Middle East in any significant way in 2016—barring the universe of unforeseen circumstances that might arise from the current instability.

President Barack Obama has engaged in what might be called a “Fabian Strategy” with regard to IS. This strategy precludes a major military engagement in favor of smaller, more nimble operations that revolve around things like airstrikes and Special Forces missions. In theory, this kind of strategy will lead to victory by attrition, having exhausted the resources of IS, while giving local forces space to maneuver and attack. The problem with this strategy is that it is not running congruently with a firmly articulated legislative solution that can course-correct the kinds of political grievances that gave cause to IS in the first place.

In the most simplistic of terms, this leads to a position of intractability that favors the conditions that IS can thrive in.

None of this is likely to change in 2016, given the temerity of election year politics and their ability to adversely influence US foreign policy. What is likely to happen is that the US will continue to work through global partnerships such as the International Syria Support Group and the United Nations (UN) to affect change in Syria, while working bilaterally with countries such as Iraq, Russia and Turkey to deconflict airspace, coordinate operations and develop methods to deny IS access to global financial markets.

These, unfortunately, are baby steps and are not indicative of an overarching foreign policy that can accommodate the many state and non-state actors who will shape the modern Middle East’s future. Until that happens, the US will struggle to maintain credibility in areas where the Islamic State is most entrenched: Iraq and Syria.

US Election Year Politicking

Where does one even begin? Let me first state implicitly that you should always be wary of candidates who claim to have a silver bullet solution to the foreign policy challenges in the Middle East. The situation has grown beyond any one plan that might shape outcomes clearly favorable to the US. And as the presidential elections grow closer, so too will the unsubstantiated rhetoric about what is possible in the war against the Islamic State.

The good news is that in 2015, the IS caliphate finally hit the limit of its territorial expansion. And the group will continue to lose ground next year given the overwhelming international response aligning against it.

This is a dangerous trap for the unsuspecting to fall prey to, and here are some examples why.

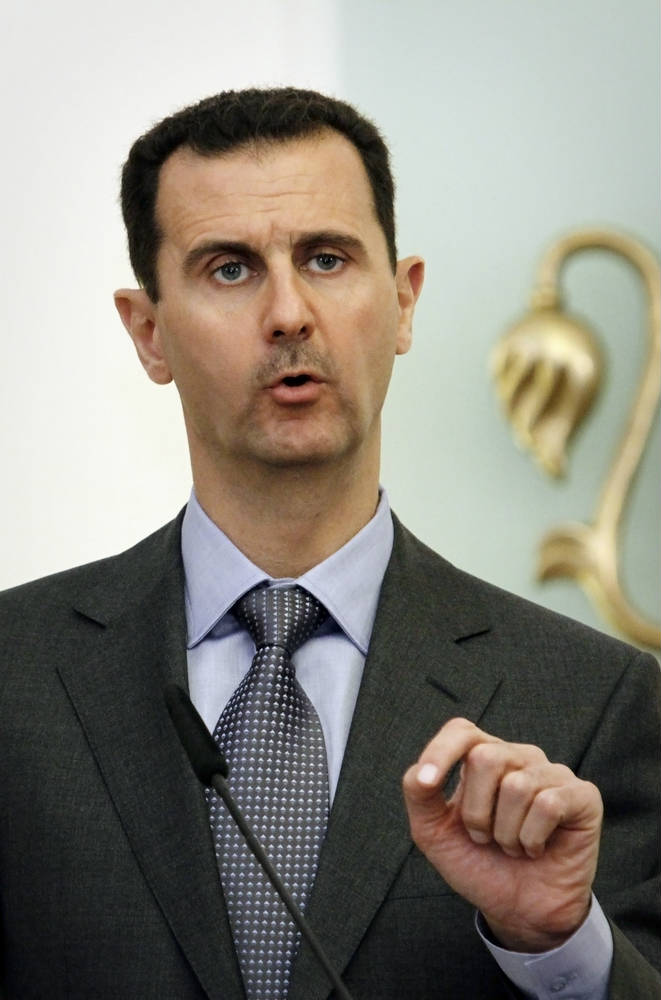

A no-fly zone in Syria is not possible, given Russia’s military support to the regime of President Bashar al-Assad. If implemented, the US and Russia would potentially be in direct military confrontation over airspace, which would not only exacerbate the conflict, but offer zero net result in either the fight against IS or the removal of Assad from power. This policy might have been possible in the early stages of the conflict in 2011, but that time has now definitely passed.

The “boots on the ground” scenario (beyond Special Forces) will not be possible for one simple reason: US troops would have to stage from Iraq, and the Iraqi government along with Iraqi civil society would neither authorize nor accept such a deployment, making this scenario little more than casual blunderbuss.

Then there are calls to arm the Kurds directly. Assuming this is the Peshmerga, it is important to remember that they are also part of Iraq, and to arm them outside of the central government in Baghdad is to undermine the legitimacy of the Iraqi state. This would also set the Iraqi government and the US in opposition to one another, since arming a faction independent of Baghdad could potentially lead to a breakdown in cooperation over fighting IS and provide space for countries like Iran and Russia to further increase their influence.

Moving away from these talking points, what will soon be obvious is that all serious foreign policy proposals from the US presidential candidates in 2016—regardless of which party—will slowly start to resemble one another. This is because most options are quite limited, and most serious foreign policy professionals know this. They might differ in tone or rhetorical presentation, but in practice they will not be wildly different from what is currently taking place.

Syria’s Hard Tomorrow

There has been some good news for Syria at the end of 2015, even if only tentative. After meetings held in Vienna in November by the International Syria Support Group, the UN Security Council has unanimously agreed on a resolution to map a path toward an eventual peace process, starting sometime in January 2016. This resolution, however, deviates along some very serious fault lines that have yet to be predetermined.

For starters, it does not address the issue of Assad personally. This is obviously an attempt to placate Russia, but it also undermines the legitimacy of the resolution for the Syrian rebel groups who will be insistent on his departure. Nor does the resolution address the question of rebel groups like Jabhat al-Nusra, which the US labels a terrorist organization, yet is one of the most powerful factions in Syria.

Then there is the critical issue of how to implement a ceasefire in a country that has, for all intents and purposes, broken down into various statelets and cantons—not to mention whose authority this could possibly be executed under.

Nonetheless, the diplomatic push is a significant development leading into 2016 and should be viewed as a victory for US Secretary of State John Kerry, who managed to bring together countries like Russia, Iran and Saudi Arabia to support this resolution.

The year 2016 will be a capstone moment for Syria, given the burgeoning UN agreement and global alignment on IS, but the prognosis is still unfavorable. Policy positions in Syria seem to be retroactive under the premise that the country can be put back together again, which is highly unlikely for all the reasons mentioned above. On top of this, there is still no regional strategy that accounts for the fact that Iraq and Syria have become one continuous battlefield, and until that happens, the conditions to defeat IS will remain elusive.

Happy New Year

There you have it, a quick and dirty round-up of where 2015 finished and what 2016 might look like from some of the key players in Middle East. Hopefully this overview has provided you a modicum of perspective that might be useful as you move into 2016 (or as conversation starters for any New Year’s Eve cocktail party).

But just to reinforce how complex the situation will remain in 2016, I did not even attempt to touch upon Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Libya, Russia, Israel and Palestine, or how they connect to the foreign policies of Western coalition countries. For that, I would have to write you a much longer missive, but that will have to wait until the new year.

*[Note: This article was updated on December 30, 2015, at 18:00 GMT.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Thomas Koch / Valentina Petrov / Photo Story / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.