Syrian refugees in Yemen must be protected from exploitation.

Perhaps one of the most efficient ways to comprehend the political and economic situation in Yemen is to see who the beggars in the streets are. The common scene would involve Africans or Yemeni marginalized communities begging at every traffic light in the local bazaars.

In 2010, the streets were filled with Internally Displaced People from the northern city of Saada and the southern city of Abyan — a war-zone between Houthi rebels and government forces, and an al-Qaeda stronghold respectively. At the time, popular discourse was dominated by desperation due to the country’s situation, since Yemeni citizens themselves were forced to come onto the streets after all their possessions were ruined by internal political wars.

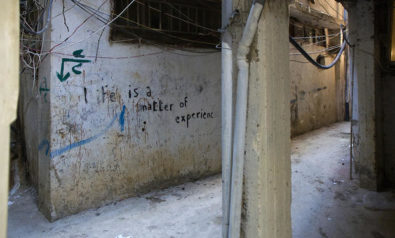

This summer, however, new scenes of beggary in Yemeni streets were shocking. The white-skinned, blue- or green-eyed Syrians are today standing at traffic lights or local markets and asking for money to somehow turn the wheel of life.

This scene has raised so many questions in my head, a fact that pushed me to do what another Yemeni girl would think a thousand times before doing.

Because “Yemen is a Good Country for Refugees”

The first group of Syrian refugees I met were all from Dara’a, in southern Syria. They arrived in Yemen from Jordan, where they lived in the al-Zaatari refugee camp, to which they fled “after their houses were bombed and some family members were shot dead.” The refugees complained about the poor conditions in the camp which is located in a desert. Described by some Syrians, the camp was “where they would sleep on the sand with scorpions” — adding that the sanitary conditions were very bad, since “the washing rooms had no water for days.” They described the al-Zaatari camp as a “prison in the middle of a desert,” as they were not allowed to leave the area.

According to these refugees, an informal association — or how the Syrians described it, “a group of people who wanted to help” — came to the camp and offered to pay for their tickets to Yemen, because “Yemen is a good country for refugees.”

Such a statement has left me bewildered, as Yemen is the poorest country in the Arab world, not to mention that Yemenis themselves are in need of help. But the reply from these Syrian refugees was even more shocking: They said that Jordan didn’t want them, and Yemen was the last resort.

The refugees entered Yemen legally and were granted a three-month stay, after which they are required to obtain a residence permit. Therefore, they are treated as tourists rather than refugees. Obtaining the residence permit is a complicated procedure, which varies from one city to another, and from one person to another. In fact, Yemeni officials have announced that residence permits will only be issued to Syrian refugees if they have a Yemeni guarantor.

However, for example, when these Syrian refugees who are based in Aden went to the immigration department of the city, they were asked to pay for the residence permit. For them, the cost of the permit varied from $50 to $100. However, when I went to the Immigration Department in Aden, I was told that every Syrian should pay $100 (21,000 Yemeni Riyals), while any other foreigner who is not a refugee is required to pay $18 (3800 Yemeni Riyals).

Moreover, it is also noteworthy to mention that these Syrian refugees were not received at Yemeni airports — whether in Sana’a or Aden International Airport — by officials who explained legal measurements, nor was there anyone to give them any type of guiding support.

The organization these Syrian refugees have sought help from is the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

So far, I have personally dealt with almost 140 Syrian refugees in Aden (25 families), and only a few of them have registered with the UNHCR. Some refugees stated that they haven’t received any aid from the UN agency, despite being in Yemen for almost six months. Others stated that the UN-issued document is costly — the document allows the Syrians to move freely in Yemen, but not work or study.

Upon hearing such statements, I decided to contact the UNHCR, and was told that “the priority is given to the Horn of Africa refugees,” while the process of Refugee Status Determination wasn’t even conducted for Syrians.

After running a quick online search for UNHCR statistics on refugees in Yemen, I noticed that separate accounts for Syrian refugees are not made — they might be counted under the “Various” category, if anything. Notably, in some Yemeni newspapers, it has been stated that the UN agency has registered 144 Syrian families, which is a significant underestimate.

For these Syrian refugees, the residence permit is needed so they can obtain rental housing — and so they can work. Since the Syrians do not have these permits, they are obliged to stay in hotels, the only alternative to staying on the street. The hotel costs $14, which is not a small amount by Yemeni standards. To afford the cost of the hotel, the Syrians are forced to beg on the streets, an act they have never done before.

The money they receive from begging is used to pay for hotel costs, leaving them without food, clothes and medicine. This situation cannot last for much longer. When the compassion of people stops, Syrians will be forced to live on the streets.

Indeed, Yemen’s own citizens are lost in the spiral of corruption, lawlessness and marginalization. But as Yemenis, we have acquired the culture of corruption and found our way through the labyrinth of bureaucracy. The Syrians are still freshmen in this science. Therefore, they are left to their own fate and the international organizations.

Aiding Syrian Refugees in Yemen

It is clear that the constant inflow of refugees from the Horn of Africa, as well as the Internally Displaced People in Yemen, are overshadowing the issues of Syrian refugees. However, the situation of the Syrians is additionally complicated by the legal obstacles they are facing.

The solutions provided by several campaigns founded by young Yemenis offer short-term solutions. The campaigns try to offer basic needs, such as food, clothes, medicines and some money — the quantity of which depends on the amount of donations and charity obtained. However, such donations in the long-term are not feasible, since Yemenis are not in a stable financial position themselves.

The problems which Syrian refugees face should not be neglected, however, especially in such a country like Yemen, where the soil for terrorism is ready to absorb poor people and push them into extremist groups. Therefore, it is in both the national and international interests to protect Syrian refugees from such potential exploitation.

If there is a feasible, long-term solution, then it should be conducted by the Yemeni government and international organizations, by providing refugees with housing, basic needs, livelihood, and legal documents allowing them to work in the country. Syrian refugees should have a special status and treatment in Yemen, and should not be treated as tourists.

The international community and human rights organizations need to pay more attention to the dire situation of Syrians in Yemen, as they deserve to be admitted as refugees of war, and not left to their own fate.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment