Only the United Nations has the ability to rescue Syria from what it has quickly become – a staging ground for a regional power struggle between respective Sunni and Shi’a backed forces.

Syria’s unique position on the map – it lies on the Mediterranean Sea and shares borders with Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, Israel, and Lebanon – is like a keystone that holds the surrounding elements in place. The outbreak of civil war in Syria has weakened the central government’s control over vast areas of the country, opening up space for new actors to operate in the pursuit of their own strategic interests. The struggle of Syria’s Sunni-based opposition against the ruling minority Alawis (an offshoot sect of Shi’a Islam) has become a proxy confrontation between two opposing factions: Iran and Russia on the one side, and Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United States on the other. Who can bring all of these parties together and implement a political solution?

Riding the Shi’a Express: Tehran to Beirut, via Baghdad and Damascus

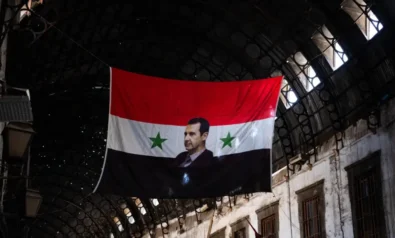

As a vocal opponent of Western hegemony and the self-anointed voice of the Shi’a faithful, Iran has been a strong supporter of the Bashar al-Assad regime. Until now, Syria’s strategic orientation has provided Iran with an ability to interfere in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through local paramilitary groups. The fall of Assad would most likely limit Iran’s regional ambitions while pushing its proxies to look elsewhere for support. Uncertainty surrounding Syria already prompted senior Hamas officials to flee the country and agree to a reconciliation agreement with domestic rivals Fatah. Similarly, the loss of Syrian sponsorship could isolate Hezbollah, weakening its leverage in Lebanese politics. It is for these reasons that Iran has reportedly sent money, surveillance equipment, and even members of its elite Quds Force in a desperate bid to keep the Iran-friendly dictator in power, despite having publicly called on Assad to listen to the demands of his people.

The victory of a predominantly Sunni opposition over an unpopular Alawi dictator in Syria would embolden Iraq’s own Sunni population and contribute to instability in the country. Tensions between Iraq’s Sunni, Shi’a, and Kurdish politicians remains heated, with the Shi'a Iraqi Prime Minister, Nouri al-Maliki, recently accusing Turkey of meddling in the country’s internal affairs. At the same time, the Foreign Ministry has warned that Sunni jihadist fighters are crossing the border into Syria to launch attacks against Assad.

Russia has used its place on the UN Security Council to vocally oppose Western intervention in Syria. Assad’s security services are an important client for the Russian arms industry, whose sales to Syria doubled in recent years. Syria also hosts Russia’s only Mediterranean naval base in the coastal city of Tartus in an agreement dating from Soviet times. In the wider picture, Russia is looking to retain its relevance in a region where its two closest allies, Syria and Iran, are losing international support and domestic legitimacy.

A Sunni Coalition for the Containment of Iran

Similarly, there are widespread reports that Saudi Arabia and Qatar are the main financial and military backers of the mainly Sunni Syrian opposition. King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia has long been angered by Assad’s willingness to carry out Iranian intentions in Lebanon and Palestine, where the countries have often backed rival factions. At the same time, there are concerns that independent Saudis are joining and/or funding jihadist movements in Syria, radicalizing elements of the resistance.

A more moderate Sunni power is Turkey, which after years of pursuing a ‘zero problems’ policy with its neighbors, has taken a bold stance against Assad. The country currently hosts at least 30,000 Syrian refugees, including prominent members of the opposition Syrian National Council (SNC) and Free Syrian Army (FSA). Previously, Turkey and Syria enjoyed strong economic relations and a visa-free agreement. However, relations soured when Turkey’s calls for political reform went unheeded by the Syrian authorities. Turkey was quick to criticize Assad after the Arab uprisings bolstered Turkey’s soft power in the region. Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development (AKP) party has emerged as a model for moderate Sunni parties (such as the Muslim Brotherhood's Freedom and Justice Party in Egypt) that have recently won elections throughout the region. Turkey is now reaching out to similar groups in Syria, effectively betting that a future Syrian government will be composed of moderates from the country’s Sunni majority.

Western allies have publicly backed Turkish Prime Minister Reçep Tayyip Erdogan in his confrontation with Assad, particularly after a Turkish reconnaissance jet was shot down after briefly entering Syrian airspace. While the United States does not have direct interests in Syria, it is keen to avoid any potential spill over into Iraq, Jordan, and to a greater extent Lebanon. After the withdrawal of Syrian troops in 2005 from Lebanon and the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah, the US has been an important contributor of economic assistance to Beirut’s frail unity government, providing hundreds of millions of dollars towards building the capacities of national institutions and bolstering the non-sectarian security forces. Though the defeat of the Syrian army could weaken Hezbollah in the long-term, heightened insecurity surrounding the country’s vast chemical weapons stockpiles poses an immediate threat to Israel.

Together with their American counterparts, European intelligence agents have been present on the Turkey-Syria border, assisting in the defection of Syrian military officers and regulating the disbursement of financial and material support to the opposition. The Western-backed ‘Friends of Syria Group’ has been important in rallying international pressure against the Assad regime and boosting the legitimacy of the Syrian opposition. The early move by the EU and others to implement economic sanctions had a heavy effect on the Syrian economy; the EU is by far Syria’s largest trading partner and consumes 95 percent of the country’s oil and gas exports.

International Problems Require International Solutions

While international powers are scrambling to secure political real estate in post-Assad Syria, the dissipation of the central government has left over 20mn Syrians wondering who can now best defend their interests. Currently, Syria is in a critical stage of the crisis, when fear and mutual distrust have the potential to irretrievably unravel the social fabric holding the country together. While nation-states will pursue their own short-term interests as defined by regional tensions between Sunnis and Shi’as, the UN is the only credible mediator who can advance the long-term interests of the Syrian people for peace and coexistence.

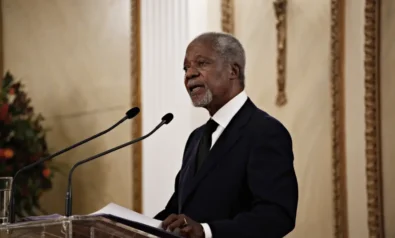

Firstly, as a forum for multilateral discussion, the UN can develop a regional consensus for a common solution and call out member states if they become uncooperative. Secondly, the UN Secretariat’s thousands of international civil servants provide it with the neutrality and diversity that make it the ideal mediator in situations such as these. With this in mind, it is telling that the five permanent members of the Security Council unanimously agreed on the establishment of a UN Supervision Mission in Syria (UNSMIS) and the appointment of former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan as the Joint Special Envoy on the Syrian Crisis.

Annan has admitted that his six-point plan for peace is failing, but as a former Secretary-General he understands that the UN is only as strong as the political will of its member states, particularly those in the Security Council. Likewise, the suspension of UNSMIS before the end of its 90-day mandate demonstrates how the UN must ultimately rely on the Syrian government for guaranteeing its security on the ground. But Annan’s role, above all else, is to build a sense of confidence among all parties. For an agreement to be reached, everyone must trust that each party will stick to the plan and not undertake destructive actions in the pursuit of short-term gains over one another.

Domestic actors must also be confident that, when they turn against the Assad regime, they will enjoy the support of the international community. The high profile defections of Brigadier General Manaf Tlass and Nawaf Fares, give hope that the barrier of fear has broken. The number of defections has not yet reached a tipping point, but the transfer of respected military and political leaders to the opposition does weaken Assad’s legitimacy and hastens the chances of a more inclusive political settlement.

The Syrian Endgame

We already know what a political solution could look like. In the ‘Principles and Guidelines on a Syrian-led Transition’, the members of the UN-backed Action Group on Syria laid out plans for the creation of a ‘transitional governing body’ established with the mutual consent of both the Assad regime and opposition groups. The transitional body would be entrusted with establishing an inclusive national dialogue, a new constitutional order, and multi-party elections. The Geneva agreement also calls for the existing make-up of public institutions (including the police and army forces) to remain intact, avoiding the sort of de'Ba'athification that led to a deadly political and security vacuum in post-Saddam Iraq.

Members of the Syrian opposition were angered by the agreement, which they say leaves the door open for regime insiders in a future Syria. However, if there is to be any hope for a political settlement, Assad must be provided with a way to exit with dignity and Syria’s minorities must be confident of a place in a pluralistic society. As one commentator put it, only Annan understands the fact “that any lasting political settlement must not be a triumph of one side or the other.” In Yemen, where former president Ali Abdullah Saleh maintained the loyalty of significant portions of the army, international mediators convinced him to handover power to his deputy in exchange for legal immunity. The UN is now doing all that it can to persuade Assad to do the same, thereby avoiding the violent fate of Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi.

Though a military solution in unlikely, as the Syrian army loses their grip over entire areas of the country, more regime insiders will realize it is high time to jump off the sinking ship. The UN has laid the foundations so that, when this critical mass is reached, Syria’s divided opposition members and diverse population groups can coalesce around a clear transition plan that guarantees their fundamental rights and enjoys the backing of the international community. When a transfer of power is eventually achieved, it will be the result of keeping communication channels open with all sides of the conflict and refraining from alienating those parties that are hesitant – for now, at least – to see Assad step down. Damage to the country’s economy and infrastructure has already set Syria back years in terms of development, but a prolonged militarization will sow the seeds for decades of sectarian turmoil. For these reasons at least, and in the absence of any other credible plans, a UN-backed political solution is still worth believing in.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment