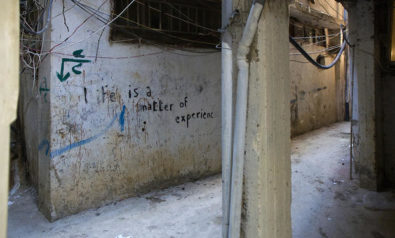

Palestinian, Iraqi, and Syrian refugees in Jordan, share similar experiences of life in exile. This is the last of a two part series. Read part one here.

Employment

Another area demonstrating the standard of living for these refugees results from a lack of citizenship, employment, freedom of movement, and protection. All three refugee populations experience hardships with ascertaining employment, with statistics highlighting that this difficulty is felt in the following order by: Palestinians, Iraqis, and Syrians.

It is apparent that those refugees with a longer residence in Jordan have elevated opportunities of employment. Nevertheless, employment is sporadic, insufficient, and sometimes exploitive. Any refugee caught working is subjected to deportation, yet they need to work in order to survive. The accumulation of one Iraqi refugee’s average salary required several years just to afford a television set. One Syrian refugee reported he works illegally “for 12 hours a day to earn $200 in month.”

In such penury like this, prostitution rates and child labor and trafficking occur, with a higher rate victimizing the Iraqi and consecutively, the Syrian populations more than the Palestinians.

Freedom of Movement

In regards to freedom of movement, all three refugee groups experience psychological torment due to the fact that they are not permitted to obtain a visa to visit their families abroad. The degrees of hardship tend to differ, however. For example, many Syrian refugees in the Zataari camp who wish to return to Syria, some in order to fight with the Syrian rebels, are forcibly deterred by Jordanian authorities. Interviews indicate that some who bribe the security and those who have a financial sponsor, are allowed to leave the Zataari camp.

There are also stories that heavily armed smugglers have conducted illegal para-military operations, helping some Syrian refugees in the camp to escape. This regulation of movement is two-fold as well. Some Syrians report, like Iraqi refugees, that they were arbitrarily turned back by border guards several times when attempting to enter Jordan. Syrians also report a difficult experience at the airport when flying into Jordan.

Although Iraqis are not hurdled into enclaves, they are also in a difficult enigma as they are only allowed to visit another country if they risk their lives by traveling to that respective country’s embassy in Baghdad, where the majority of violence in Iraq occurs. Unregistered Syrian and Iraqi refugees both reported that they do not register with governmental agencies because this limits their mobility within and traveling out of Jordan. It also subjects them to surveillance by Jordanian and foreign intelligence agencies. One Iraqi stated: “They send people with eyes all the time. They find us when we register.”

For Palestinian refugees, the hope of returning to their homeland is non-existent for many of them. Gaza Camp residents are not even given a passport by the Jordanian government. One Palestinian lamented: “I do not have an ID to own [a] car, go to school, travel… What can I do?” Another Palestinian without statehood mourned:

“We have such difficult times being Palestinian from Gaza since we don’t have the nationality-citizenship — whatever you call it. Everything related to the nationality is always so complicated: getting a job; traveling abroad; [a] driving license, which you have to renew every single year; [a] job licensure [is] not easy to obtain. I can’t get any scholarship[s], even if I scored in the top three [of] my classes in school which is very frustrating.”

Furthermore, fresh-off-the-boat Palestinian refugees entering Jordan from Syria are treated worse than Syrian refugees. They are often detained, arrested, or deported back to Syria. Those who are accepted into Jordan are heavily concentrated in camps with stricter regulations, harsher conditions, and segregated from Syrian refugee camps.

Lack of Protection

Although Jordan has done an outstanding job at protecting their “guests” or refugees from external threats, these different refugee populations lack the full and equal protection of the government as Jordanians. This equates into a plethora of incidents where the native population takes advantage of these victims of war. Rents and food prices are purposely raised by natives at the immediate realization that a new refugee population approaches.

The author himself witnessed a venal landlord, without guile, turn off the lights and water to an entire apartment building in order to coerce tenants to leave; so he could welcome higher paying refugees. The brunt of such victimization occurs less with Palestinians, more with Iraqis, and much more with urban Syrian refugees.

Such lack of protection by the government also involves physical abuse and violence by the native population. For example, urban Syrian refugees report incidents with more frequency in comparison to Iraqis and Palestinians, in regards to kidnappings, abusive harassment, and forced prostitution. Sometimes, a disagreement between a Jordanian and a refugee may result in the immediate proscribing and deportation of the latter, rather than reprimanding the culprit of the animosity.

Interviews indicate that unregistered refugees are unable to use the regular instruments of the Jordanian law against their assailants and do not have the right to due process. One Iraqi, when speaking of his own experience with the preceding example, quickly pointed both of his hands downward, suddenly stomped his right foot while twisting his foot left to right — as if to put out a cigarette — and asserted: “we are here!”

In sum, it is clear that the rising levels of refugees have sparked emotions of difficulty, fear, and jealousy among some in the native population’s lives, which translates into discrimination based on weak canards and portended umbrages. There are insufficient or non-existent laws to protect the refugees from those who may choose to employ their discriminatory discretion.

Future Outlook

As the global economy deteriorates, the volatile situation for all these refugees and Jordan grows worse. King Abdullah of Jordan has rightly argued that an increase of international aid is vital. The Jordanians have demonstrated a consistently large heart in accepting many refugees who flee persecution and death by pouring into its borders.

With a 12 percent budget deficit, Jordan is placed in a precarious and dangerous position by international inaction. As one Syrian refugee commented: “Jordan has difficulty helping because it is a small country.” Jordan continuously struggles to avoid the Arab Spring from reaching the confines of its own sovereignty. There have been ignored and marginalized eruptions of mass protests; solicitous journalists being assaulted or harassed; police officers and protestors being shot or physically harmed; police stations being over-run; internet sites being blocked; Molotov cocktail attacks; politically motivated incarcerations; and more.

The level of this activity is much less than in other countries, yet they are warnings of an impending danger within the labile belly of Jordan. The fledging Jordanian economy, in combination with a growing refugee population, has been a catalyst for a possible ignition of this powder keg. Jordan desperately requires a concerted international response to the refugee equation in the country in order to preclude this.

The future outlook for the refugees of Jordan is also abysmal, without a sudden and significant proliferation of international aid. What is needed is more direct accounting of aid distribution supervisors; more omnipresent and unbiased agencies to directly supervise the distribution of aid and offer protection and services for these refugees with puissance; and the granting of more rights by the Jordanian government.

These are only temporary answers, however. Yet, they are exigent, as one Syrian refugee commented about waiting for a political solution: “To the people who wait for the regime to collapse, more people will die.”

The long-term solution is apparent: the armed conflict in the refugees’ countries of origin needs to be squashed and these refugees should be compensated for their losses and protected if repatriated; or they should be given the full rights as other citizens enjoy within their country of refuge, or in another.

Refoulement, the act of forcibly removing the refugee back to his or her country, is absolutely not an option until the former demand of security and compensation is met. To accept anything contrary to these drafted suggestions would be a travesty. Otherwise, the frightening situation for Syrian and Iraqi refugees is that their lengthy stay in exile will become like what most of the registered and unregistered Palestinians — who were interviewed — complained of being: a permanent lost people without a homeland living as an unequal and oppressed minority in another.

As one Syrian refugee stated about her possible resolution during an Al Jazeera interview: “I don’t care if Assad is still there. As long as I can go back to Syria. I hope we don’t have the same destiny as the Palestinians,. who fled their country and never got back again.”

*[Note: The author wishes to thank Miles Shelly and Max Marin for their valuable assistance.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment