The people who suffer the most at the hands of our monsters are the ones we do not care to see, says Maria Khwaja.

It is 3:50AM in Amman, Jordan. The call to prayer echoes across the city. I have just finished suhoor, the morning Ramadan meal. We are meant to be 30 minutes from the Syrian border today visiting refugees who live outside the camps. In over a decade of working in East Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, the worry that eats at me is always the same.

There are so many children. Children in the streets, children in overcrowded classrooms, children excitedly following us around and shouting muzungu, ajnabee, Amreekan.

There are so many children.

I’ve seen it in Karachi, where bright-eyed Afghan children watched me from behind cement walls. In Jordan, we have already spent time being followed by dusty mobs of Palestinian children in Gaza Camp. One ramshackle playground, under the watchful eye of an elderly headmaster, exists for them to play away from the danger of cars and strangers.

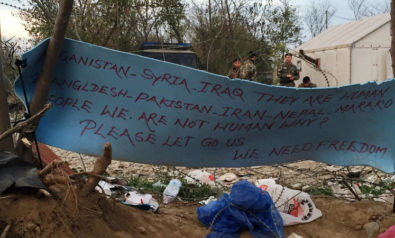

These children are all growing up in conflict and post-conflict zones, victims of the wars we are all involved in and victimized by corrupt systems and corrupt politicians in expensive cars. There is little education—overcrowded classrooms and haggard staff—and little hope for the future. It is a trick of contemporary media that our definition of “refugee” means a quick image of fragile boats in the Mediterranean without consideration for the generational ramifications of what we are allowing to exist.

They are alive, that’s about all we can say. Making sure they have jobs, homes and health care is not our problem, after all. We feed them like we feed street cats and are pleased that they are still alive.

Our Frankensteins

Robert Fisk theorized that it was the asceticism and the stark despair of the refugee camps in Pakistan that molded the views of the Taliban. I know, personally, good people who the Pakistani Taliban blew up or shot in Karachi. I know, and have held, children who sit in their homes traumatized by firecrackers because they sound horrifyingly like a Kalashnikov.

I had tea once in a cement courtyard with a woman from the Northern Areas in Pakistan. She had been bombed out of her home by the Pakistani military trying to force out the Taliban who had crossed the borders. Her mother, a wrinkled old woman wrapped in a traditional chador, came out weeping, carrying a black comb and whispering in Pashto that it was the only thing she had left of her home.

We are meant to be 30 minutes from the Syrian border today visiting refugees who live outside the camps. In over a decade of working in East Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, the worry that eats at me is always the same.

Muslims, refugees embrace or encourage extremism? As they say in Turkey, the political horses dance, but it is the innocents, the grass under their feet, who are trampled. Extremism across the entire world, in hate speech and government posturing, is the great plague of our times. Let’s not pretend there’s only one brand of it when, in America, a classroom full of 6-year-olds doesn’t stir us to action.

Our Frankensteins were not born from nothing.

The people who suffer the most at the hands of our monsters are the ones we do not care to see—the ones who live in an endless round of overcrowded government offices and weep at the end of sanitized photos.

We have a word for it in Urdu that I hear used often: majboori. It is a word that is difficult to translate, but equates roughly to what people must do in a state that academics might call “capability deprivation.” It is the blank faces of the men I have seen sitting on street corners who must work dangerous construction jobs because they have no other option to provide for their children. It is the blatant, startling inflation of rent prices by Turkish landlords that must be paid, the faces of mothers who follow me in the street begging for milk for their children, the Kurdish families in Istanbul who pick through trash instead of going to the camps because of the harassment they would receive as Shias.

Part of me, the same part that taught in an urban American classroom, is jaded. I expect the begging and pleading, the fingers that reach out to grab my shirt and wave UNHCR registration papers. I expect the stories of drug abuse and fatalism. Generational trauma is a documented phenomenon and we don’t even have enough social workers for our own population, much less those abroad, not because we can’t fund it but because we don’t prioritize human dignity.

We cannot feed children guns and expect them to survive. We cannot write entire populations off as collateral damage.

Refuse to Yield

I don’t have feelings anymore toward these things because there is nothing to say except no. No, there is no justification for taking a life or for proxy wars. No, I will not be afraid of pointing out the problems I see in US foreign policy. No, I will not turn on my neighbor. No, I will not stop insisting on reform within Muslim communities. No, I will not apologize for a death cult, much like I will not apologize for the Taliban, because I see the faces of the people they terrorize firsthand and, trust me, I hate them more than you do.

No, I will not forget the faces of the children who made me promise to come back.

We are taught in Islam that there is a great karmic blessing in giving, in lifting the majboori off another. If we have enough for one and another arrives, we are meant to split our food in two. It is no accident that the Middle East is known for hospitality, that in Swahili and Arabic the words heard most often are karibu and marhaba (welcome). If we have even a little, we are meant to give it away joyfully because there is no loss in the sharing.

I have shared in fresh honey in a Nepalese village with Tibetan refugees and witnessed the same practice. There is no loss in providing sweetness, comfort and dignity to another. There is no loss in sharing.

Perhaps this is why I cannot stomach the attitude of “it’s not my problem.” Or perhaps I am wondering what is to become of millions of children without a future.

No, I will not let the comfortable thought of a full belly and a soft couch and hours of Netflix lull me into forgetting. This is why I fast in Ramadan, like all of my community if they choose, because in abstaining I am reminded of what matters in the end: discipline, integrity, compassion, serving others to the best of our ability.

These are lessons I was taught as a Muslim, but they are lessons that are not unique to Islam or to any religious tradition. These are the lessons the world learned from Muhammad Ali and celebrated after his death, forgetting that he was an unapologetic black Muslim man. They are human lessons.

We must refuse to yield, like Ali, in the face of fear and despair and grief. We must remember that there are entire generations that we are choosing to forsake. The war against extremism and corruption and indifference will be lost only when good people are too frightened or apathetic to say anything. In memory of those whose lives should not have been taken on every side, we cannot yield. In constant compassion toward those who suffer daily on all sides, we cannot yield.

We cannot stop standing up for each other, unified, because that is when extremists on all sides win.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Abul-Hasanat Siddique

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.