Turkey has a long path ahead before all of its citizens can enjoy the full benefits of citizenship.

On August 10, Turkey directly elected its president for the first time since the republic was founded in 1923. Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the former prime minister, won the election, which called 55 million citizens to the ballot boxes. Gaining 51.79% of the vote, he prevailed over his opponents: Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, former secretary-general of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and joint candidate of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) among others; and Selahattin Demirtaş, co-chair of the People’s Democratic Party (HDP).

On August 28, Erdogan took over the presidency from his predecessor, Abdullah Gul, in an official ceremony held at the Cankaya presidential palace in Ankara. Political tensions surrounded the oath ceremony, due to the delayed publication of the election results — although the Supreme Board of Elections (YSK) declared the end of the counting procedure on August 15. Usually, any regulation or amendment made to the law is expected to be published the same day or the day after; in case of official elections, the results should be distributed as soon as the final counting is formally announced by the YSK. The delay has been repeatedly denounced by the opposition as an open violation of the Turkish constitution. The main points of criticism were based on the acts and meetings held by then President-elect Erdogan during the 13-day delay, during which he also served as prime minister and chairman of his party. During this transition period, Erdogan also announced the designation of Ahmet Davutoglu, former foreign minister, as the new chairman of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and new prime minister.

President Erdogan has consistently been a key player in Turkish politics and the wider Middle East since the general elections of 2002. The 12th president of the republic is a charismatic figure influenced by and promoting political Sunni Islam. In December 2013, his leadership and the AKP’s reputation were blemished by a corruption scandal that involved several people very close to the government, the Gezi Park protests in summer 2013 and Erdogan’s harsh political rhetoric toward his opponents, especially the Hizmet movement and its leader, the Muslim scholar Fethullah Gülen.

Admittedly, under Erdogan’s premiership, the country has achieved several goals, including consolidating its role as a regional power and global actor, as well as an economic powerhouse.

Partially thanks to Turkey’s candidacy for European Union (EU) membership, civil liberties and human rights have improved and it could easily be asserted that the last ten years represent the golden age of modern Turkey. But at the same time, it is crucial to emphasize Erdogan’s negative impact on the country’s human rights situation. Of particular note are the 2011 general elections, in which the AKP won 327 seats out of 550 in the Grand National Assembly (TBMM), gaining the right to lead a single-party government for another term, and the Gezi Park protests.

Turkey has been ruled by a single-party authoritarian government, creating tension among its citizens and threatening basic human rights.

Gezi Park has been and still is seen as the turning point of the current administration’s behavior and reputation at the domestic and international level. After the Occupy Gezi clashes erupted in all major Turkish cities and were suppressed by security forces with an indiscriminate use of tear gas and water cannons — a practice condemned by all the national nongovernmental organizations (NGO), as well the EU, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International — the governance style of Turkey’s leading party completely changed.

Gezi Protests: A Turning Point for Human Rights in Turkey

Since the protests, Turkey has been ruled by a single-party authoritarian government, creating tension among its citizens and threatening basic human rights. Moreover, the situation has worsened in the wake of the 2013 bribery case. Over a 12-month period, Turkey witnessed restrictions on media and Internet freedom, with a temporary ban of Twitter and YouTube and an increase of attacks and legal complaints against journalists, as extensively documented by Index on Censorships and BIANET, a Turkish independent news site.

Furthermore, an interim report by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) openly denounced the lack of nonpartisan journalism covering the recent ballots. Censorship has not only affected the coverage of the presidential election. After the prime minister called on the media to not report any news about the abduction of Turkish diplomats and soldiers by the Islamic State in Mosul, an Ankara court issued a prohibitive order on airing or publishing any news related to the situation of the hostages. On June 17, the ban was imposed with immediate effect on all media executives by Turkey’s Supreme Board of Radio and Television (RTUK).

Freedom of expression is just one of the civil society’s concerns right now. On August 1, the Istanbul Convention, a legal milestone on preventing and combating gender-based and domestic violence, came into force. Turkey was the treaty’s first signatory in 2011, but the situation of women in the country is still under threat.

Moreover, during the holidays marking the end of Ramadan, Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç expressed his concerns about the conduct that women should observe in the public sphere, including calling on them to not laugh in public. This could be misinterpreted as perpetuating an anachronistic patriarchal order. The vision seems to be shared by Erdogan as well. In one of his electoral rallies, he used violent words indirectly targeting a prominent journalist, defining her as a “shameless and militant woman” who must know her place. Amberin Zaman, a columnist for Taraf and The Economist, and her colleague, Ceyda Karan from the Cumhuriyet Daily, have been the targets of a libelous campaign on social media only for their professional observations on the status of Turkish politics.

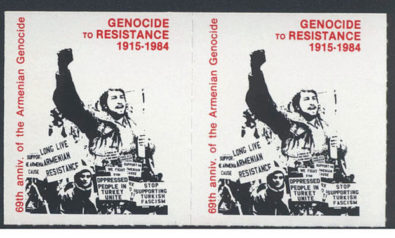

The 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide is on April 24, 2015. The mass deportations and deaths suffered by the non-Muslim population under the Ottoman Empire in 1915 will be commemorated worldwide.

Another very important topic that will affect the post-electoral period and the upcoming political agenda are minority rights. Only three minorities are recognized in Turkey: Armenians, Greeks and Jews. According to Articles 37-44 of the Treaty of Lausanne, these minorities enjoy rights from freedom of expression and religion to education. Even nowadays, almost a century after the foundation of the Turkish republic, there is no legal provision for other communities or for non-Sunni Muslim groups. There has been a rise in the use of discriminatory language to target opponents, which negatively affects the daily life of the many Turks not considered members of official minority groups. This racism, perpetuated by university textbooks and election rallies, leaves an uncertain future for Turkey’s non-protected minorities.

The Armenian Genocide and the Alevi Controversy

The 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide is on April 24, 2015. The mass deportations and deaths suffered by the non-Muslim population under the Ottoman Empire in 1915 will be commemorated worldwide. The centenary will be the occasion to better understand Turkey’s treatment of its citizens belonging to different ethnic groups. The remembrance presents the threat of confrontation among Turks and citizens of different ethnicities.

Unfortunately, since the assassination of Hrant Dink in 2007 — a famous Turkish-Armenian journalist and editor-in-chief of Agos, a bilingual Turkish-Armenian weekly — one can observe an escalation of incendiary rhetoric toward the Armenian community. The fight over the recognition of events in 1915 as a genocide even extends beyond Turkey’s borders. For instance, it has evoked nationalism in Turkish communities living abroad that are trying to counter the commemorations in countries such as the United States, Australia and Canada. Other minority communities will honor their dead as well and openly confront Turkish denialism; for instance, there will be commemorations of the Seyfo Genocide suffered by the Assyrian minority under Ottoman rule.

Furthermore, according to a 2013 Agos report and later on confirmed by the interior ministry, the “officially recognized” minorities are subjected to a race code classification by the education ministry as a legacy of the Ottoman educational system. According to the report, the code for Armenians is two, the Greek minority is classified with code one and the Jewish minority is number three. This practice could amount to illegal ethnicity-based data collection and profiling of current and future generations.

Those who support a confrontation with Turkey’s past are being subjected to discrimination and hate speech. For instance, movie director Fatih Akın — after an interview published with Agos about his new movie The Cut, which alludes to the Armenian genocide — has been officially threatened alongside with Agos by the Turkic Pan-Turanist Association’s Ötüken Journal. The association has openly declared its intentions to fight any attempt to recognize the events of 1915 as genocide.

From a political perspective, despite the words pronounced by then-Prime Minister Erdogan on the eve of the 99th anniversary, in which he offered his condolences toward Turkish citizens of Armenian origin, attitudes to this minority have not changed. Labeling someone as Armenian is still considered an insult by many conservative Turks. Recently, Erdogan was invited by the Armenian president, Serzh Sargsyan, to attend the Genocide commemoration ceremony next April in Yerevan. At the time of writing, there was still no official reply from the Turkish president or the government.

Muslim minorities, particularly the Alevis, are experiencing significant discrimination as well. The Alevis, an heterogeneous and heterodox Muslim community, represent the largest religious minority in Turkey. They cannot freely practice their faith and their houses of prayer, the Cemevis, are not officially recognized as places of worship by the Directorate of Religious Affairs. The community has suffered several massacres (Dersim, Maraş, Çorum and Sivaş), and is still one of the preferred targets of discrimination from a political point of view.

The fight against ultranationalism and discrimination, alongside the creation of a pluralistic environment supportive of human rights, is the final task of the democratization process under Erdogan. Despite several achievements of the AKP’s era — from the ending of the headscarf ban to the unofficial recognition of Alevis’ worship houses — there is still a long path ahead for equal rights for all peoples in Turkey.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment