A historical overview of the relationship between Italy and Libya and its legacy for Libya’s current situation in the ‘Arab Spring’.

On March 17th, the United Nations Security Council approved Resolution 1973 establishing a no-fly zone over Libya. Almost instantly, Italy volunteered the use of a Sicilian air force base and other logistical support. That same day, Italians marked the 150th anniversary of their unified state. But another approaching anniversary is unlikely to be commemorated: on November 1st, 1911, Italian planes attacking Tripolitania’s Ottoman forces dropped four bombs on the outskirts of Tripoli. This was the first aerial bombardment in world history.

News analyses of what is happening in Libya today have rarely mentioned Italy’s role in the country’s creation. Similarly, too little has been said about the depth of Italy’s political and economic involvement with Libya, at present and over the last 100 years – especially by Italian authorities, who appear to hold their breath on the subject of Italy’s colonial past.

Libya’s Colonial Origins

The 1911 assault on Tripoli was followed by a somewhat premature declaration of victory in 1912: it took some years before Italian forces controlled most of the province. Italy’s efforts to dominate the neighboring, also Ottoman, province of Cyrenaica and its principal city, Benghazi, were troubled from the beginning by sustained political and military resistance, largely coordinated by the Sanusi brotherhood. Initially, the colonial government attempted a mixture of force and compromise, agreeing to the formation of a Cyrenaican Parliament in 1920. However, Mussolini’s seizure of power in 1922 soon translated into a war for total control in the colonial territories.

This war entailed concentration camps, public executions, the clogging of vital water sources, and a barbed-wire barrier preventing crucial supplies from flowing in via Egypt. It is commonly referred to by scholars, politicians and Libyans alike as genocide: the numbers killed in the process can never be certain, but there is no debate as to the fascist government’s attempt to exterminate the population, or its partial success in doing so. A furthereffect of this war was large-scale emigration that exacerbated the future country’s demographic losses.

In 1931, Italian forces captured senior resistance leader ‘Umar al-Mukhtar, and hanged him; by 1932, the colonizers had achieved what they cheerily described as a modern-day Pax Romana. This victory enabled Italy in 1934 to form a unifiedLibya comprised of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and the inland desert of the Fazzan. Finally, in 1939, the two coastal provinces were annexed to Italy, just as France had annexed parts of Algeria in the 19th century. For a few years, much of what we know as Libya today was Italy.

In short order, the Libyan desert became one of the theatres for World War II – not just Tobruk, but the entire region, where abandoned landmines have maimed Libyans for decades and fueled ferocious, never-ending anti-colonial sentiment up until today, 60 years after Libya’s independence in 1951.

Frenemies in High Places: Why Berlusconi Has Needed Qadhafi

One irony of the current events is that while Qadhafi someday may face the International Criminal Court for attempting what his opponents on the ground and international powers are calling attempted genocide, no Italians were ever tried for the atrocities and abuses they perpetrated in colonial or World War II Libya.

This omission (minor perhaps in the global rearrangements, including the prosecutions of Nazis, after war’s end) is part of what allowed Italian Foreign Minister Franco Frattini to warn in February that the Libyan uprising could cause an “exodus of biblical proportions,” without acknowledging that his own country had prompted the former colony’s first “exodus” of people fleeing subjugation and possible death.

Italy and Libya have certainly had their political differences during Qadhafi’s rule, but Italy has also long been Libya’s major economic trade partner: for financial reasons alone, it has had an implicit interest in Qadhafi staying in power. Hence, until very recently, its resounding silence regarding current events, which it broke only to emphasize the topic of migration.

Even now that the Italian government has sided with the revolutionaries’ Libyan National Transitional Council, its Prime Minister is silent. Unlike the many other national leaders who have spoken up about the extraordinary battle for Libya, in which the Arab League and Libyan citizens support NATO intervention, Berlusconi has disassociated himself, and left it to Frattini to serve as the face and voice of his government.

Why? Beyond the Italian state’s financial ties to Libya, Berlusconi has long depended on the mercurial, sometimes threatening figure of Qadhafi for some of his own political capital. He and Qadhafi have syncopated their threats of unbridled migration beautifully over the course of recent years. One of the Libyan dictator’s first responses to foreign intervention on March 19 was to warn that he would no longer respect agreements to prevent migrants from crossing to Europe – giving substance to Frattini’s warning, but also returning to familiar rhetorical territory. This oft-reiterated menace has put Berlusconi repeatedly in a position to shore up his image as the sole obstacle protecting nervous Italians from hordes of Africans invading – colonizing – Italy.

Berlusconi has found other uses for Qadhafi, as he will reach for anything to distract the Italian electorate from his notorious problems as their leader. It’s not just that, as Vanity Fair put it in 2009, Qadhafi makes the Italian Prime Minister “look positively somber and statesman-like”; Berlusconi also tried to deflect attention from his dalliances with under-age women, for which he now faces trial, by blaming the Libyan leader for initiating him into “bunga bunga parties”with them.

This is a two-way street, with advantages for both sides.

Why Qadhafi Needed Berlusconi

Since the revolution he led in 1969, Qadhafi has unceasingly invoked the horrors of the colonial past to legitimize his authority. Still now, he continues to accuse the opposition of inviting outsiders to colonize Libya, positioning himself as the only imaginable bulwark against inevitable foreign occupation. This stance paid off in 2008 when he mustered both financial and political capital from the accords he signed with Berlusconi, who promised Libya long-demanded reparations for damages caused by Italian colonization.

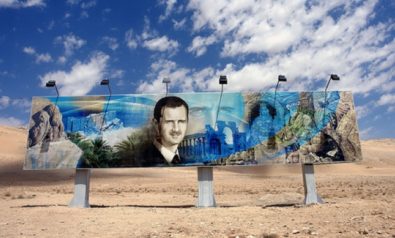

As a symbolic gesture to mark the event, the Italian Prime Minister returned the Venus of Cyrene, an ancient piece of statuary taken in the colonial era. Qadhafi portrayed himself on this occasion as finally defeating the former colonial foe, and forcing it to return what had been wrongly taken. The transaction can be seen in a display at the National Museum, in urban murals across Tripoli, and even in postcards that show the two leaders gazing appreciatively at the sculpture’s headless, armless, and nude female form. The phrase “bunga bunga”comes to mind.

Qadhafi’s exploitation of the colonial past has also been blatant in his long-standing appropriation of the memory of ‘Umar al-Mukhtar, the very emblem of Cyrenaica’s resistance to Italian forces. Qadhafi has consistently suppressed Sanusi political authority — the king he deposed in 1969 was Idris al-Sanusi — while hijacking both its image and the history of its resistance, making his use and abuse of the rebel leader’s memory all the more egregious. The timeworn photograph of al-Mukhtar’s profile appearing throughout footage of the uprising shows that eastern Libyans have taken back their heroic heritage. ‘Umar al-Mukhtar represents their opposition, no longer to Italian occupation alone, but to Qadhafi’s brutal rule and on-going assault as well.

Can Libya Remain Unified?

For the same reason, it is no accident that the rebels have adopted Libya’s pre-Qadhafi flag to represent their revolution and their future nation. Upon what will this nation be built? Recent discussions have highlighted the prevalence of tribal divisions and networks in Libyan politics. What has been acknowledged far less is that under the cloak of Libyan unity — another subject Qadhafi and his spokesmen have been invoking — Qadhafi’s state not only plays tribes against each other; it also oppresses Libya’s remaining minority. Christians and Jews left long ago, but Berbers have not been permitted an independent ethnic identity.

News coverage of Italy’s celebrations on March 17th dwelled, for good reason, on the fact that many Italians are unenthusiastic about Italy’s unification, even 150 years later. In Libya, which is striving for a new unity and independence on the 60th anniversary of its first independence and on the centennial of Italy’s first attack, we may be witnessing the forging of a new national sentiment, one that can override internal divisions and will not require isolation from other nations to endure.

Qadhafi as Mussolini

Ultimately, the greatest irony of this historic moment is that Qadhafi has already replaced Italians in Libyan memory as the perpetrator of genocide. In the name of anti-colonialism, he has been waging a war on his own people not unlike the one Italian forces conducted in the 1920s, and he has become the very thing that he has claimed to oppose.

But he is not the sole culprit. Berlusconi, who stated he didn’t wish to “disturb” his “friend” with pleas on behalf of Libyan civilians when the uprising began, must be seen as complicit in Qadhafi’s enduring reign. He has benefited from Qadhafi’s long stay in power, and he stands to lose politically and financially when Qadhafi falls. Who knows? Perhaps he can offer the Libyan dictator refuge when he finally steps down.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment