What is the root cause of conflict in the modern Middle East?

The ideals of diversity and difference—the notion of a mosaic society—are amiable, but in reality these terms mean nothing without equality, without which there is no peace. As soon as one tribe regards itself as more prized than the other, it is the beginning of every conflict. This experience is as old as history, and little is going to change it because it is hardwired into human existence. In order to regard instinctual behavior as group survival, human beings need not be externally challenged by another group.

Nature, the environment and the need to survive has created a predisposition on the part of human beings to survive in competition with the other. In the very seeds of existence lies the basis of human destruction. Thus, conflict has been a function of human history since the very beginning of human existence. Conflict resolution, therefore, ought to be about the need to solve the problems without exaggerating them. The current solutions, however, point to a lack of solutions, and therefore, the problems go on and on.

In 1852, Karl Marx wrote that history repeats itself, first as a tragedy, then as a farce. Today’s conflicts have many reasons. First, there is the geopolitical factor as the overriding dynamic. It is not specifically ethnic or cultural. Second, there is the sectarian, which is an internal quagmire that faces groups in nation-states. Third, there is the spiritual versus the material conflict that exists in Muslim societies wrestling with how to deal with a Godly world without God, as they see it.

All of these lead to class conflicts, competition for resources, inequality and social conflict as the norm. Potentially, there is a need for the spiritual to come to fore, hence the ongoing internal uncertainty, and how it is influenced from outside forces because of the lack of internal change and development to meet expectations and desires of societies as a whole.

The Internal Challenges

As a way to respond to national challenges as a result of despotism, militarism and disenfranchisement, and as nation-states allude to geopolitical aspirations, leaving the “left behind” communities virtually on their own, dislocated and alienated, marginalized groups resist the dominant paradigms, which are present on a global, not only national level. The conflicts emerging in the Middle East today are about the loss of a local identity and the lacking ability of nation-states to facilitate social mobility, equality and fairness for the “left behind.” The Arab Spring that began in 2010 is a case in point. Theirs is a reaction against the very geopolitical paradigms that are pulling nation-state elites toward a global bipolar paradigm between neoliberalism and the rest.

Internal challenges in societies that lead to violent conflict and affect young Muslims in the Middle East can be defined in four ways. The first are revenge seekers, those groups who allude to a global ideological framework in relation to a so-called war on Islam. The second are status seekers, people whose opportunities have been thwarted in the context of social conflict. The third are identity seekers, groups whose sense of themselves has been compromised as a result of being “left behind.” And finally the thrill seekers, those who want a form of adventurism in the context of the decline of masculinity, thwarted by the breakdown of traditional masculine roles in society, compounded by the Internet, and the loss of physical and sexual confidence.

While there are social revolutions of the classical kind, some young Muslims are motivated by activism sustained by a more radical interpretation of Islamic texts. It is not the texts themselves that necessarily create the opportunities, but their reading. This Salafism only emerged in the 1960s, not before. It lends itself to the idea that it came from outside of nation-states. Where, initially, there was resistance against elites, now it is against society as a whole, as it is seen as culpable too.

Presently, the current form of dominant Salafism is an anti-globalization movement with particularism based on the writings of a range of Islamic political ideologues, but principally Ibn Thamiyyah, Abd al-Wahhab, Abu Ala Maududi and Sayyid Qutb. It has affected Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan and vast swathes of the Muslim world in more recent periods. This type of Salafism is a form of a global cosmopolitan jihadist movement with Salafist/radical/takfirist ideology that needs to be understood within a certain framework. Sectarianism itself is not theological; rather it is a function of modernity and modern ideas as a whole.

Within the internal power structures of the Middle East and North Africa, there is a manipulation of social structures to the benefits of elites, compounded by a lack of internal checks. These dominant elites focus interest on internal conflicts, not external issues, as they benefit from external advantages and ongoing internal dissatisfaction. Internally, the education sector, the criminal justice systems, the lack of economic opportunity and the focus on security and intelligence maintains the discord among the wider population, preventing internal change and development, keeping people suppressed.

Since the immediate period after the Cold War, the events of the First Gulf War in 1991, Bosnia during the mid-1990s and Pakistan in the late 1990s, to Iraq in 2003 and the Arab Spring in 2011, a particular set of patterns in relation to aggressive Western interventions have been observed. All the while the West has had its own problems, facing increasing economic and financial challenges from the further eastern parts of the world, leading to an ever more intense focus on the Middle East itself.

The External Threats

At the heart of the problem of global conflict is the formation of capital and wealth creation based on the theory of the free market, which has become the single paradigm in which the whole world has found itself. This capital formation affects the nature and output of the media, and aspects of Orientalism, which help to propel a certain kind of propaganda, for example, about the free market. It supports modes of competition that are geopolitical, enhancing internal divisions, and maintaining the frameworks in which elites allude to an external geopolitical aspiration that is in the interests of the very few at the expense of the many.

This is also realized through aspects of the knowledge and information economy, and the reproduction of certain technological outputs that maintain the strengths of the elites; the military-industrial complex no less. It is a perennial cycle that has maintained itself in the light of the post-war period, which left only two superpowers to battle it out until the end of the Cold War. Since the early 1990s, the rise of Western capitalism has been unprecedented, even though there remains a lingering post-Cold War mode of conflict with Russia, China and India, all as part of deep state fears in relation to the legacy of communism that lingers at the very heart of this model.

In thinking through ethnicity as a specific paradigm of the Middle East, the Kurds are a group that finds itself spread across four nation-states. In the Turkish model of secularism and nationalism, it pushed Kurds south. Meanwhile, they were absorbed by Iran, Syria and Iraq to a greater extent, but not Turkey. Hence, there is also a Kurdish dimension that needs to be understood in the context of the current conflict in Syria and Iraq, but also the role of Turkey and Iran in the appreciation of a specific concern that continues to afflict the Middle East.

Moving Toward Solutions

The evidence across the world as a whole suggests that inequalities are widening. In this context, there can never be peace. There is little or no opposition to individualism, competition, cronyism and selfishness. This is the dominant framework. The solution is a spiritual one, with attention paid to the self, and with a great deal of effort it can be nurtured. Here, it is possible to move from a position of low spirituality and low power to high power and high spirituality, leading to equality and fairness for all while providing sufficient space and time for creativity, innovation and enterprise that is in the interests of human societies as a whole.

Arabs, Persians and Turks have been in conflict for a considerable period of recent history. In the post-World War I period, with the breakup of the Middle East, these existing conflicts are not entirely dissipated in light of internal weaknesses and external interests. The Gulf States, Iran and Turkey become susceptible to proxy wars, internal challenges that are militarized by external interests (through the supply of weaponry and security apparatus), and the manipulation of elites by Western interests, leading to a lack of investment in societies, or the need to suppress their aspirations through a form of misdirected or neutralized religiosity.

The balance, in relation to challenging the problems in the Middle East, is about adequately addressing elitism, which focuses entirely on looking outward and introducing a form of spiritualism and mobilizing the masses, without falling into the trap of political violence and extremism driven by a misguided ideological perspective that has helped to maintain the power structures found in certain Arab states.

During the Ottoman period, while there were a myriad of groups under the administration of the sultan, and there were expressed differences in religion and culture, no specific conflict between Jews, Christians and Muslims was evidenced, even if they were tensions. In the post-war period, this has remained the case, but the elites in Turkey have not worked out how to talk to reconcile the divide between secularism and Islamism.

After the breakup of the Middle East, the Arabs had oil, the Persians had oil, but the Turks resorted to Kemalism. Based on the ideals of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the new republic radically separated itself from the Ottoman past through secularism and liberalism. The West took advantage where they could, largely keeping Turkey close, using it as a proxy when required, and regarding it as an important ally in a complex region, as well as a bridge to Europe.

The solutions are about moving away from history toward a new theory, where scholars and scholarship are given adequate room by nation-states. Moreover, there is a need to stop blaming others and to start working together, mindful of the disinformation and misinformation that characterizes aspects of the global and local knowledge economy. There is also a need to choose between stability, security and democracy, but realizing that anti-globalization is not necessarily a sectarian question. That is, through a collective political struggle, ethnic differences could be potentially restrained in the pursuit of concerted efforts by diverse communities to challenge a situation that affects all. Conflict has many different layers in the Middle East, and it is easy to fall into the trap of binarisms.

Thus, to challenge these dominant paradigms, there is a need for a civil society that focuses on values, spirituality, equality and diversity, because social conflict is the norm. Good governance at the top needs to be combined with adequate mobilization from below, leading to the elimination of the instruments of repression, building adequate development projects, introducing wide-scale education and investing in technology, all of which are in the better interests of society as a whole, rather than the few.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

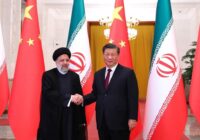

Photo Credit: ChameleonsEye / Frontpage / Shutterstock.com / Toban B. / Flickr

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment