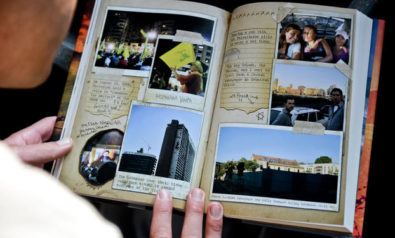

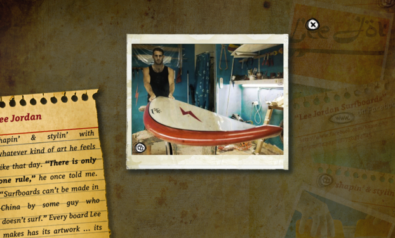

The following is the last of a six-part series of excerpts that Fair Observer will be featuring from Jesse Aizenstat's Surfing the Middle East: Deviant Journalism from the Lost Generation. Author's Note Just after completing my little journalistic experiment of surfing on both sides of the heated Israeli-Lebanese border, I realize again that this is more than just fun and games. There is a dark side to Middle East surfing. While the surfing element seems so similar to growing up near the ocean in California, the history and violence force me to remember that I’m really in the Middle East. Surfing with Nasrallah When I kick off my shoes and think back to my first day of Lebanese surfing, Jiyeh lives as something of a perfect spot for me. It was like an Eden of sorts. Yet as we walked along that frontage road to breakfast, Monner said the place had been unsurfable for years. Only recently had he started surfing it again, which made me curious about this seemingly all wonderful place. To the left of the sandbars, a few hundred yards from the break, a refinery rested at the tip of the half-moon bay that crested back out to sea. In the 2006 war, Israeli air strikes hit this refinery, causing an oil spill that seeped onto the Jiyeh shore and soaked the fine sandy beach with the dark hells of conflict. On the other side of the Jiyeh break was another remnant of battle: an old, rusty boat, perhaps 40 feet long, sunk deep enough in the sand that it wasn’t going to budge—which was fine because like most ruined things in Lebanon, nobody was going to move it. At one point while we were surfing that morning, I paddled over to the vessel and checked out its gutted cabin, to see if I could find a rusty old machine gun or something. Really, it just looked intensely cool from the surf line up and I wanted to check it out. So I paddled over to it, climbed aboard, and parked my surfboard on deck. I then performed a dive—mostly for Monner’s amusement—with a highly botched back flip, slapping the Mediterranean with a boisterous splash that stung my back for a good long moment. It is impossible to verify the actual history of a boat like this, since nearly everyone Monner and I talked to had a different story. But according to some of the owners of the beachfront resorts—and their slave-waged workers, whom we would meet on our return trips—this boat once belonged to “Palestinian arms smugglers.” It had been shelled before their cache could reach the shore. In Lebanon, there seemed to always be this pseudo-lie that sought to blame everything on the Palestinians for marching into Lebanon and eventually starting the civil war. And when that scapegoat failed, there was always another loathing Lebanese faction to blame: “F**k the SSNP!” Or Israelis. Or whoever pissed you off during your morning coffee. Regardless of whose boat it was, or how it got there, it had spent over 30 years rusting at the Jiyeh break. Later in my journey, while reading on top of some haggard old casbah in Aleppo, Syria, I stumbled upon a stomach-wrenching passage in Robert Fisk’s Pity the Nation, telling how Druze militiamen ravaged the little town in 1985. When it was over, civilians were told that they would be compensated for the hundreds of homes that had been razed. That never happened—and the Maronite churches were dynamited and bulldozed to the goddamn ground. This wasn’t exactly the first thing I was thinking about that morning, especially after the elation of finally getting to surf in Lebanon. But there it was, staring right back at me: those fine Jiyeh sandbars were triangulated by the refinery, the boat, and Jiyeh itself. That sleepy little town had more to it than just being a beautiful place with fine waves. It too had seen its fair share of the sickness that lurks along the Eastern Mediterranean. And while everything was fine at the moment I was there, who knew when the oils of war would again seep out of it? Just like Lee, with his stories about random rocket fire, Jiyeh had a dark side. Without proper conditioning, it’s easy to become exhausted by the emotional shift that comes with Middle East surfing . . . but maybe it’s that very darkness that makes it so alluring in the first place. The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment