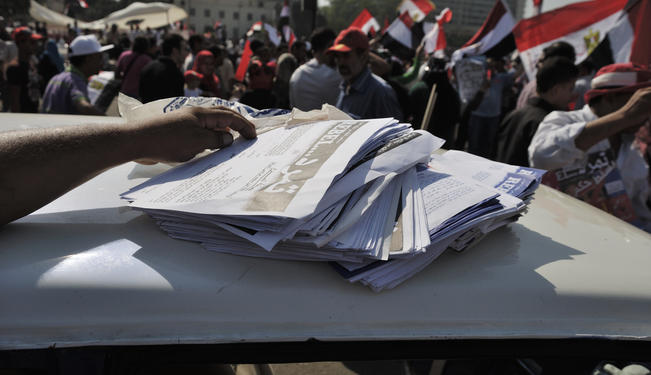

After Morsi’s ouster, all political parties must receive equal rights in the next election.

With the ouster of President Muhammad Mursi, the political transformation process in Egypt has seen a major setback. Of course, the military intervention accompanied by a suspension of the constitution, the arrest of the first democratically elected leader ever in Egypt, and the installment of an interim president, is a coup d’état and not — as it was announced by supporters of the army’s moves — a corrective action. In fact, it is not the first time this term has been used in the Arab world for a military coup. It is a sad irony that the coup was initiated by a military that did not want to go down that road, but had instead tried to make political actors from all sides of the spectrum reach a consensus right up until the coup. The military’s fear that continued self-blocking of Egypt’s political system could lead to further violence, and eventually to an ungovernable country, was entirely justified.

Egypt’s Young Democracy

Many are responsible for the misery, including, of course, President Mursi and his Muslim Brotherhood. The biggest accusation which can be made against Mursi is he did not understand — or was unwilling to realize — that such a tight election like the one in 2012 comes with certain responsibilities. Especially in a young democracy like Egypt’s, it was important to have a broad-based government to unify the country.

Meanwhile, Mursi lost many supporters who had backed him a year ago. The most damage to his image was certainly done by the way he pushed through controversial parts of the constitution, and thereby tried to put himself above the judiciary. The Muslim Brotherhood and their Freedom and Justice Party, which was the main support base for Mursi, continued to be a nontransparent cadre organization that was formed by decades of illegality and persecution, and held no prior governmental experience. Authoritarian actions directed at critical journalists and activists from civil society only antagonized youths of the revolution. In addition, there was wide spread disappointment that Egypt’s economic and social conditions had not improved during Mursi’s time in power.

The Opposition: Blockingthe System

However, this is where the responsibility of other political actors comes into play. Leaders of the main opposition parties, who like to be called liberal or even secular, agreed on letting Mursi fail. Therefore, they blocked the system —for example, by their early announcement to boycott parliamentary elections they couldn’t win – toyed with the idea of violence on the streets, and hoped for the military to intervene in their favor.

Leaders of the judiciary, and large parts of the old bureaucratic elite, couldn’t stand that Mursi won the election and contributed their part to thwart his success: for instance, by dissolving parliament that had been elected in early 2012. After which, the president remained the only freely elected authority besides the upper house of parliament. Drafts for new election laws had been rejected by the judiciary many times, as had other legislative proposals. Much needed economic and sociopolitical reforms, such as the signing of the painfully negotiated credit agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), remained unfinished.

At first, the military had accepted Mursi but considered itself to be a kind of supreme guard of the state and public order. An agreement between Mursi and the opposition to form a government of national unity would most likely have been preferred by the military leaders over a coup. The military’s chief of staff and its leaders do not want to rule the country. Memories of angry protests against the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) are still too fresh. Accusations against the military, at the time, were not significantly different from what the protest movement accused Mursi of: an autocratic style of government, the devastating economic and social conditions, and “theft” of the revolution.

Not All is Lost

In fact, not all accomplishments of the uprisings, or the revolution of 2011, have been undone. The most important one is probably the awareness that despite all contradictions of public debate, governments are not legitimate by themselves but have to represent the will of the people. This also means that every government, whether it was elected or not, will have to face mass protest if they cut back on democratic freedoms or fail to take necessary measures to revive the economy.

There are no reasons for German and European politicians to accept or even approve of the coup d’état against Mursi. However, there is no way back either. The request to reinstall the constitution — which at least contains a human rights catalogue, and besides all its flaws is better that none — should be pushed by European governments.

Beyond that, they can only appeal for Egypt to hold parliamentary elections as early as possible and to make sure that all actors in the political spectrum, including the Muslim Brotherhood, get a fair chance. Oppression and persecution of the ousted president’s supporters would send a signal to Islamist parties and streams all across the Arab world that democracy is, after all, not an option; at least not for them.

*[This article was originally by Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), and translated from German to English by Annika Schall. This article was updated on July 8.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment