Refugees are seen as a burden by the EU. But for Brazilians, born into a country of miscegenation, someone’s origin is not an issue.

“Wow, you’re Brazilian! Brazilians are so cool, so nice, so generous! I’ve never met people so open as Brazilians.”

I have heard this response many times after introducing myself abroad. And I’ve heard this in places as different as Kenya, France and Lebanon—and from people ranging from students and diplomats to janitors, from the young to the old, from men to women.

Even if this is a generalization, living outside of Brazil makes one see things in their own country from different perspectives. Especially in a moment such as this when news headlines in Europe are focused on the migration crisis.

Mixed Origin in Brazil

Brazil is a melting pot not only because of its origins as a Portuguese colony, its indigenous people and the African slaves who were brought to the country centuries ago. Historically, Brazil has also had a remarkable record on hosting people from all over the world, like the Italian, Japanese and Lebanese migrants who disembarked in São Paulo at the beginning of the 20th century, looking for a place to build a new life.

The result? Together with the United States, Canada and Argentina, Brazil has received one of the largest numbers of immigrants in the Western Hemisphere. Statistics from the first census conducted in 1982 until another completed in the year 2000 show that Brazil has received at least 6 million immigrants.

The number of refugees currently recognized in the country is around 7,700. Still a small number when compared to countries like Pakistan, which hosts 1.8 million refugees, but the number in Brazil has been growing exponentially due to the “humanitarian visas” granted to Syrians escaping the war. Limited housing and public services, as well as restricted access to documents and jobs, are big challenges facing refugees and migrants in Brazil, especially in the midst of an economic crisis. Nevertheless, in 2015, the Brazilian government authorized the permanent residency of more than 40,000 Haitians and, so far in 2016, of nearly another 10,000 African migrants.

In practical terms this means that nowadays in Brazil, everyone has mixed origin. Last names can look German or Syrian, and Brazilians have never paid much attention to this. But while hosting migrants and refugees seems to be the nightmare of the century for Europe, one can cherish the solidarity with foreigners in places like Brazil.

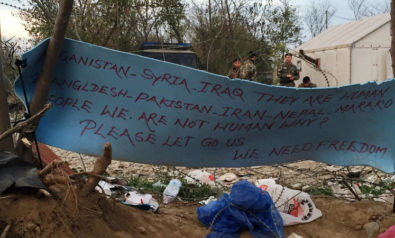

It is alarming that refugees and migrants have become a “crisis” for Europe when Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Turkey—the countries neighboring Syria—are hosting more than 4.8 million refugees. And in Syria itself, there are currently more than 7.6 million people displaced from their homes by the conflict that is in its fifth year. The solutions that Europe is creating to deal with the influx of migrants are concerning because they are primarily geared toward security. The economics of migration and the human potential of migration are being dramatically undervalued.

EU Deal With Turkey

In September 2015, the European Union (EU) agreed to resettle 160,000 refugees disembarking in Italy and Greece over a period of two years. Enormous debates between member states took place over which “measure, quota or burden” of refugees they would take in. The relocation scheme, however, did not work out and in January, only 272 asylum-seekers had been relocated, according to the EU Migration Commission. To make matters worse, Macedonia and other countries in the Balkans have decided to close their borders, leaving thousands of refugees stranded in Greece.

On March 17, European Union (EU) representatives met in Brussels to look for solutions, and Turkey proposed to accept all the “irregular migrants.” For “each Syrian brought back, another would be resettled in Europe.” There are two important issues to consider: It is hard to believe that this could work, and forcibly displacing people is against international law. And a bigger issue: Migrants and refugees do not want to stay in Greece or Turkey, so they would probably look for alternative routes to Europe.

Furthermore, Turkey is basing its proposal on “humanitarian purposes” when, in January, the international medical organization Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) denounced in a report that the EU’s policies worsened the crisis. “Not only did the European Union and European governments collectively fail to address the crisis, but their focus on policies of deterrence along with their chaotic response to the humanitarian needs of those who flee actively worsened the conditions of thousands of vulnerable men, women and children,” said Brice de le Vingne, director of operations for MSF.

During a recent conference in Geneva, representatives from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) also stressed that the lack of cooperation between European countries was propelling the migration crisis. For these organizations, the future involves strong political leadership committed toward protecting refugees and migrants—Chancellor Angela Merkel’s open position to accepting refugees in Germany has been quoted as a model for Europe—and creating a dialogue for reaching pragmatic solutions preserved in legal mechanisms like the Refugee Convention.

What should be done is the big question, and a major part of the answer lies in rethinking how to host and protect people. This question does not only concern Europe, as in 2015 the world reached a record number of 60 million displaced people.

It means globally that one out of every 122 humans is now either a refugee, internally displaced or seeking asylum. Migrants comprise 244 million people, or 3.3% of the world’s population living outside their country of origin, according to the United Nations.

It means globally that one out of every 122 humans is now either a refugee, internally displaced or seeking asylum. Migrants comprise 244 million people, or 3.3% of the world’s population living outside their country of origin, according to the United Nations.

Historically, countries neighboring sites of war and disaster, like Iran and Kenya, have hosted more refugees than any others. Refugees are mostly found in underdeveloped countries in the Middle East, Africa and Asia, according to the UNHCR.

Refugees and Migrants Are Seen As Numbers

Brazil and Latin America are responding with creativity and by strengthening their hosting traditions to foreigners. Actions vary from pilot projects to promote employment schemes in Brazil for Colombian refugees, to student visas for Syrians in Mexico and bold regional agreements, like the roadmap adopted in Brasilia in 2014 by Latin American and Caribbean countries to address new displacement trends and end statelessness within the next decade. Meanwhile in North America, Canada is investing on remarkable new resettlement programs financed by private organizations and individuals.

“We need to put men back in the center of the problem. It is the only solution. Today, refugees and migrants are foreigners, numbers,” a North African migrant told me during a phone call.

He has been detained for three months in a Center of Identification and Expulsion (CIE) in Sicily—a type of center that local nongovernmental organizations are asking to be closed down because of their precarious conditions, and where migrants and asylum-seekers are detained straight after arriving in Italy.

When opportunity is given instead of limitations, people adapt and flourish, like a migrant teenager from Gambia who I interviewed in Sicily. He traveled to Europe alone crossing the sea in a boat that almost drowned, after having been arrested for four months in Libya. Thanks to an Italian family who hosted him, he learned Italian, had his documents and could join soccer training in a local club. His biggest dream: to become a professional football player.

“You’re Brazilian! Great! So you also love football, you can understand me,” he told me.

*[This article was originally published by plus55, a partner institution of Fair Observer.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Orlok / De Visu / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.