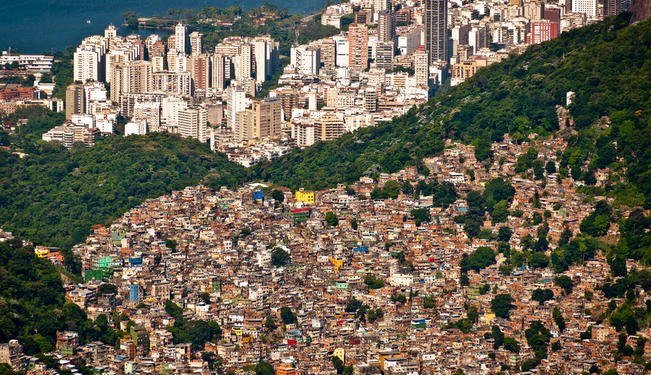

Forced evictions are happening throughout Brazil, exacerbating the country’s growing inequality.

In the early morning hours on January 7, Brazilian city officials arrived in the favela slum of Metrô-Mangueira in Rio de Janeiro to forcibly evict the families living there. In total, 12 homes, some of which still had their residents’ belongings inside, were demolished, sending tremors throughout the neighborhood. When the outraged residents took to the streets in protest, police fired pepper spray, tear gas and rubber bullets as protesters returned fire with rocks and bottles.

This particular favela is located less than half a mile from Macarana Stadium, where the final FIFA World Cup match will be played this summer.

So far, thousands of people have been forcibly removed from their homes in Rio de Janeiro. According to city law, victims of forced evictions must be relocated close to their previous homes.

But many are being relocated to the outskirts of the city, far away from their previous residences. And the compensation packages of $22,000 for families forced to relocate have been described as inadequate for a country where real estate prices are rising rapidly.

Unfortunately, these evictions are not limited to just Rio de Janeiro. Forced evictions are happening throughout the country, and they are only one of the myriad problems facing Brazil’s poor in the midst of its World Cup and Olympic preparations.

Who Benefits?

As the 12 Brazilian cities that will host events prepare for an influx of foreign visitors, they have launched a host of construction projects to build stadiums and improve roads, public transportation and airports.

By August 2013, after years of efforts, only half the stadiums were ready, and an estimated $3.2 billion had already been spent — a figure three times more than the original budget. The majority of that money came from the public treasury, despite an initial promise from the sports minister that no taxpayer money would be used to build or rehabilitate stadiums.

To add insult to injury, after the stadiums are built, they will be handed over to private firms to operate. These firms, not the Brazilian people, will reap the benefits of this enormous taxpayer expense.

The Brazilian government claims that building and rehabilitating stadiums will spur development in the surrounding neighborhoods. Even as their taxpayer dollars are forked over to private developers, officials assure the public they will benefit from upgrades to roads, hospitals and other infrastructure.

These same claims were made in South Africa during its preparations for the World Cup in 2010, and they proved to be illusory. South Africa spent $6 billion on its stadiums for the World Cup, which FIFA and South Africa’s Local Organizing Committee promised would boost the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) by around 3%.

However, shortly after the games ended, the South African Finance Ministry revealed there was only a 0.4% boost. Out of the ten stadiums that were built or rehabilitated, nine became what are called “white elephants” — venues that are too large for local use and essentially become a waste of space and money. The Brazilian government’s audit courts found that at least four of Brazil’s 12 stadiums were likely to become white elephants.

The controversy surrounding the stadiums just compounds Brazil’s problem of inequality.

Last summer, when the Brazilian government proposed a fare hike for public transportation in Rio de Janiero and Sao Paulo, it was met with resounding protest. Thousands took to the streets in demonstrations against the 20-cent increase in fares, soon expanding their grievances to include the country’s failing public sector and ballooning inequality.

As always, the poor are the hardest hit: Brazilians making minimum wage earn just $313 a month, while dealing with a staggering annual inflation rate of 6.5%. Thousands of Brazilians living in favelas have little to no access to hospitals.

But the protests showed that middle-class Brazilians are growing increasingly restive as well. At 36% of GDP, Brazil ranked 12th out of the 30 countries with the highest tax burdens in 2011.

Yet despite exorbitantly high taxes and a booming economy, the public sector still has ample room for improvement. Brazil’s education system, for example, is performing poorly: In 2009, the literacy and math skills of Brazilian 15-year-olds ranked 53rd out of 65 countries.

The extravagant expense of the World Cup, of course, did not go unmentioned by protesters. How could the Brazilian government spend billions on an international mega-event, while the basic needs of so many go unmet?

An Insult to Soccer

Played by 250 million people in virtually every corner of the map, soccer is the most popular sport in the world. For one month this summer, soccer fans all over the planet will don their jerseys, crowd their bars, and cheer their teams on to victory. The atmosphere will be electric in Brazil and around the world.

The host country should strive to make sure its whole population benefits from the World Cup. It is an important event and a rare opportunity for our world to come together, despite our differences to celebrate hard work and (mostly) friendly competition. However, the blatant discrimination against the poor puts the World Cup in a negative light.

Using public money to build shiny new stadiums while not investing in education or public health is morally bankrupt. Evicting people from their homes and leaving them with little to live on is a gross injustice to the people of Brazil and fans of soccer worldwide.

It is time for the Brazilian government to reevaluate its policies and priorities. Surely, government officials and FIFA officials can come together to figure out a way to have an economically sound and socially responsible event.

Home to world-class footballer Pele and the winner of five World Cups (more than any other nation), Brazil is no stranger to soccer. Die-hard Brazilian fans are known for being among the most loyal supporters in international soccer, but even they have limits. Their intense love of soccer is now overshadowed by their need for economic and social justice.

For those who love sports and justice, it may be difficult to enjoy the World Cup this summer.

*[This article was originally published by Foreign Policy In Focus.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment