As the conflicts in Syria and Iraq continue into 2016, the refugee crisis is the responsibility of the entire international community.

Background

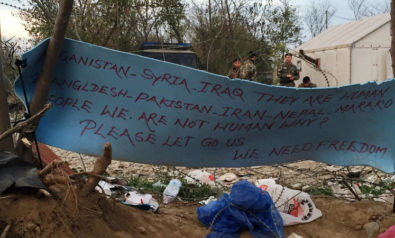

The sight of shabby boats packed to the brim with refugees fleeing war-torn countries like Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan was a prevalent image for the year 2015.

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), at least 1 million migrants entered Europe last year, with over 800,000 of those traveling from Turkey to Greece—half of them Syrian. The figures for 2014 were 280,000 detected migrants, and 570,000 asylum applications.

What is far more troubling than this exodus is the numbers of those who do not make it to Europe’s shores. Just in the first quarter of 2015, the death toll was far over 1,500, compared with 96 during the first four months of 2014. The IOM estimates that over 3,770 people died last year.

For a long time, member states of the European Union (EU) have looked to Germany to solve the issue. In September, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban stated: “The problem is not a European problem, the problem is a German problem.” Indeed, Germany is the most sought-after destination among the refugees. The country was expected to take in at least 800,000 asylum seekers in 2015 alone, while reports on December 30 said Germany had seen almost 1.1 million migrants enter the country.

Applying for asylum is a lengthy and complex process. Protected under international law, the system sets standards and procedures for processing and assessing asylum applications, and for the treatment of both asylum seekers and those who are granted refugee status. Once they claim refugee status, they cannot be returned to the home country against their will.

According to the Asylum Quarterly Report conducted by Eurostat, the number of first-time asylum applicants rose sharply in April 2015—from around 35,000 in 2014 to 55,000 in 2015—reaching 90,000 by June. Germany has 38% of these applicants; Hungary and Austria are the next highest; and Italy, France, and Sweden account for around 7%.

The reason Germany is the most sought after country for Syrians is because it affords special refugee status, whereby refugees are allowed to claim asylum in Germany even if they arrive at another EU country first. Migrants coming from “safe countries of origin,” like Serbia, Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, are deported within a year.

“Ukraine, the Greek question and the migrant issue show how powerful Germany has become in Europe against its own will, how central the German government is to solve these big European questions,” said Christoph Schult, of the German magazine Der Spiegel. “I think the chancellor is not particularly happy about that role and would prefer others to collaborate or take the lead.”

Indeed, over 50% of Germans are reportedly worried about refugees arriving in the country. But it is not difficult to see why Germany holds the appeal: Anti-immigrant—particularly anti-Muslim—feeling is high in eastern Europe, with countries like Slovakia and Hungary only willing to accept Christian refugees. Poland’s foreign minister, Witold Waszczykowski, went a step further to suggest Syrian refugees—who comprise around 60% entering Europe—should form an army to “liberate their country.”

Similarly, across the Atlantic, despite President Barack Obama announcing that 10,000 Syrian refugees will be allowed to resettle in the United States in 2016—compared to just over 1,800 since 2012—more than half of state governors oppose the measure.

The Paris attacks on November 13, 2015, have only exacerbated fears of Islamist extremists using the refugee crisis as an easy avenue into the West, raising questions of not only immediate border security, but assimilation policies and radicalization prevention.

Why does the EU Migrant Crisis matter?

Much of the contention regarding resettlement quotas lies in the inability of EU member states to develop a central policy on asylum. Many EU countries have yet to properly implement any standards set previously. For example, under the Dublin Regulation, the union requires that each asylum claim be processed in the first EU country reached by the asylum seeker. Given that the main ports of arrival, like Greece, have been hit hardest by the economic crisis, a new system will need to be implemented in order to deal with the unprecedented numbers that have so far resulted in the regulation to be suspended altogether.

The United Nations has called on European states to guarantee relocation for refugees. In September, EU ministers agreed to relieve the burden on frontline countries by redistributing a further 160,000 refugees, with Germany, France and Spain due to take in the bulk. According to data released by the European Commission in November, fewer than 1,500 places have been made available so far, with 116 people actually relocated.

With the overwhelming majority of the crisis still shouldered by Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt—who together house over 4 million refugees from Syria—the world urgently needs to develop a better response to the crisis. On November 29, the EU struck a deal worth €3 billion with Turkey to stem the flow of refugees entering Europe.

As international airstrikes against the Islamic State (IS) in Syria and Iraq take on a new ferocity following the attacks in Paris and the downing of a Russian passenger plane over Egypt, the cycle of violence affecting the civilian population only intensifies. Certainly, this cannot be just “Germany’s problem,” but one that rests on the shoulders of the international community, whose past policies in places like Iraq and Afghanistan have largely precipitated the current situation in the first place.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Photoman29 / Punghi / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.