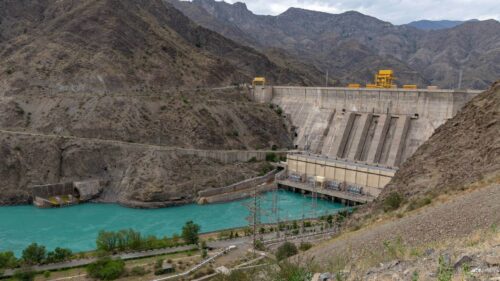

Once famous for historic battles, Sutjeska National Park in Bosnia and Herzegovina is a region of mountains and primeval forests on the border with Montenegro. More recently, lawyers have replaced soldiers. The park is now the site of legal battles, where environmental activists endeavor to prevent the construction of new hydropower projects. After ten years of fighting to protect two rivers, they succeeded in stopping construction, but only within the bounds of the national park. Despite outdated licenses and a lack of public consultation, the diggers are back to try their luck further upstream.

The last remaining free-flowing rivers in Europe exist in the Balkans, but they are in danger. Plans to build around 3,000 dams between Slovenia and Greece, along with diversions and urban developments, threaten almost every river in the region (this map shows what that number looks like in practice). Even protected areas are not immune, with around 1,000 of these projects putting vulnerable stretches of the river at risk.

If the plans to build the new hydropower plants go ahead, the impact on biodiversity would be devastating. Critically, the damage does not just take place during construction when diggers cut directly into local habitats. There is also a downstream impact on endangered ecosystems. Water quality, declines in fish and bird populations and the dislocation of sediment are only a few long-term issues. In the worst cases, the harm is irrevocable: about 50 fish species could be faced with global or regional extinction.

The local geology is also vulnerable to the change in river flow patterns from dams and diversions, which can erode land downriver and change underground water flows. During building work on the upper Neretva in Bosnia and Herzegovina, there were two fatal incidents from landslides. In many cases, the risk assessment prior to construction is insufficient.

Risky investment

From an economic point of view, hydropower plants offer an opportunity for growth and financial development in the Balkans. Investments from foreign project developers such as Chinese and American contractors bring much-needed money into the region, fueling development and providing employment opportunities.

However, investing in traditional forms of hydropower is risky. For one thing, the power plants themselves are increasingly victims of climate change. Droughts, unpredictable rainfall, heatwaves and reduced snowmelt not only inhibit the supply for drinking water and irrigation, but also reduce the resources available for generating electricity. Additionally, higher temperatures cause more water to evaporate from reservoirs, further wasting this precious resource.

The knock-on effects, when these hydropower plants are unable to meet demand, are substantial. Alongside electricity shortages leading to higher energy prices, the failure to supply energy-intensive industries can reduce economic output, cause job losses and increase poverty levels.

Furthermore, authorities can be lax in applying environmental laws, cutting corners in favor of project developers. The public, on the other hand, has minimal opportunity to get involved in the decision-making process. While this flexibility initially works in favor of the investors, it can later backfire when local communities start protesting.

Making a splash

Public activism in favor of the rivers has been gaining momentum in the Balkans. Determined to stop the dams, the environmental NGOs Riverwatch and EuroNatur launched the campaign “Save the Blue Heart of Europe”. Over the last 12 years, activists have spread the word about the scale of damage that the rivers in the Balkans are facing. “The first step is to raise awareness,” says Ulrich Eichelmann, founder of Riverwatch. “You have to make it so famous that it’s too big to fail.”

The biggest success was in Albania. After 11 years, activists — including celebrity Leonardo DiCaprio — managed to convince Prime Minister Edi Rama to create the first Wild River National Park. Crucially, efforts to raise awareness consisted not only of exposing the plans to build dams, but also of communicating the uniqueness of the river both to locals and politicians.

Managing the future

The appropriate designation and recognition of protected areas is a lifeline for sensitive habitats: this is the second step to turning hope into reality. While the Vjosa is now protected as a wild river, the delta is not included in the new national park, leaving it exposed to plans to build a luxury resort and even an airport. Urban development of this scale would devastate both the landscape and the ecosystems reliant on it.

Likewise, it is also essential that governments enshrine international conservation networks, such as Natura 2000, as well as European environmental regulations into national law. In an effort to help manage the situation, EuroNatur and Riverwatch published an assessment of the river network in the Balkans, showing which stretches of the river network are no-go areas for dams based on clearly defined environmental criteria such as biodiversity.

International funding bodies also play an important role in facilitating the effective management of protected areas by directing financial resources to the right places. While European development banks were previously planning to finance hydropower projects in the Balkans, they have now scrapped these plans after tightening biodiversity rules. Instead, financial establishments as well as the EU can show their appreciation of the unique value of these rivers by directing funding towards conservation and restoration.

Economic growth in the Balkans is not dependent on building new dams. Nor will the energy transition fail if the last wild rivers of Europe are allowed to run their natural course. Indeed, the risks outweigh the advantages, which is why the fight to prevent the construction of traditional hydropower projects is not over yet. As long as the rivers are flowing, the battle will continue to keep Europe’s blue heart beating.

[Stephen Chilimidos edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment