Analysis on Russia’s cautious decision-making and its strategy in regard to the Syrian uprising.

A crescendo of criticism in response to Russia’s refusal to join in Western and Arab-sponsored UN resolutions calling on Syrian President Bashar al-Assad is considerably off the mark. In sharp contrast to the mix of idealism and realism that tends to be at play in Western foreign policymaking, Russian leaders of the post-Soviet era have learned that a hard-nosed, at times even cynical realism is their best if not only option.

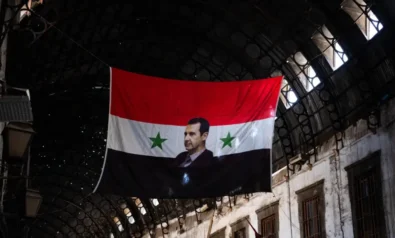

Thus, the Kremlin is focused like a laser on its own economic and security interests in Syria and desperately hopes that the situation develops in a manner suitable to Russia’s interests. For this to happen either President Assad should remain in power or his removal should come by way of a negotiated extrication, as opposed to a forced removal from power. If Russian brokering was to be the means by which Assad’s extrication occurs, so much the better for Moscow. This is the strategic calculus that underlies Moscow’s decision to not support the various Western- and Arab-backed UN resolutions that would lead to Assad’s immediate removal from power.

Russia’s overall strategic perspective derives from recent history. Moscow recalls, with a bitter taste, the West’s violation of its own UN resolutions on Kosovo and Libya. In the former, the West recognized and facilitated Kosovo’s independence, despite the UN resolution’s clear statement on preserving Serbia’s territorial integrity. Last year another UN resolution allowed NATO to establish a no-fly zone in Libya to protect the opposition being mercilessly attacked by Muammar Gaddafi’s forces, but NATO forces quickly got dragged into the civil war and helped the revolutionaries seize power and kill Gaddafi. As a consequence of this past, the Kremlin does not believe that restrictions on Western actions written into a UN resolution on Syria will be honored.

An open-ended approach to humanitarian interventions has direct implications both for Moscow and Beijing, which also voted against the Syrian crisis resolutions. They fear that a loose attitude towards humanitarian intervention could one day lead to a UN resolution allowing for Western intervention in the North Caucasus, Kaliningrad, Tibet or Xingjiang, especially if UN reforms were to remove or somehow dilute the present Security Council members’ veto power.

Another issue is whether such intervention is advisable at all in a situation with such a murky structure of strategic action among the many still unclear actors vying for power in Syria. It is unclear whether control over the situation is possible at all, and the successful securing of an outcome intended by Washington, Moscow, Beijing, or anyone else, is uncertain. Unintended consequences are more likely to rule the day. Thus, as time goes by, it is becoming clearer and clearer – as many warned – that the Egyptian, Libyan, and other revolutions of the ‘Arab Spring’ are not likely to produce the democracies that the starry-eyed Obama Administration envisaged. Rather, they are more likely to produce new forms of authoritarianism or totalitarianism; quite likely of the Islamist kind. People under the new regimes will continue to suffer, perhaps more horribly so than under previous dictatorial regimes. Thus, many Americans rightly criticize the Obama Administration for hastily jumping on the bandwagon of the supposed Arab ‘Spring’ and being deluded by naïve, indeed false assumptions about the direction these Muslim revolutions will take. However, many of the same critics are the most vocal also in admonishing Moscow for refusing to go along with Washington’s excellent new adventure.

Contrary to our romanticism about revolutions, far from all revolutions turn out to be democratic. The sooner we learn that lesson and develop new criteria and methodologies for deciding when, where and against whom we should humanitarily intervene, the better.

Russia, being in the immediate neighborhood, is caught even more tightly in this crisis. In terms of its foreign policy and interests, its approach to the Syrian crisis has logic. However, should the opposition seize power in Damascus with Moscow being perceived as having stood decidedly on Assad’s side, then Russia will likely lose the very things it seeks to save.

Even if Assad should somehow remain in power, this problem can come back to bite Moscow domestically by strengthening its own internal jihadi challenge in the North Caucasus. Syria (and Turkey, which is also seriously affected by the Syrian crisis) has a large Circassian diaspora. Hundreds of thousands of Circassians are seeking refuge in Russia from the fighting, including in their traditional Circassian-populated homelands, from which they fled Russia’s Tsarist army in the 19th century. Russia’s Kabardino-Balkariaya Republic (KBR) is suffering from a low intensity jihad at the hands of the Caucasus Emirate (CE) mujahedin’s United Vilaiyat of Kabardiya, Balkariya, and Karachai (OVKBK). The OVKBK is the CE’s second most powerful network, and it has been moving to establish a presence in another Circassian-oriented republic next door, the Karachaevo-Cherkessiya Republic (KChR). Moreover, this expansion brings the OVKBK and CE closer to Sochi – the venue for the 2014 Winter Olympic Games, which the CE has threatened to attack.

Resentment of Moscow’s veto sparked demonstrations by thousands in Syria, with elements of the opposition blaming Assad’s murder of children on Moscow and declaring jihad against Russia. Many in the Western and Arab media will play up and distort this angle, as is already happening. In addition, Saudi Arabia – a country that played no small role in the rise of jihad in Russia’s North Caucasus – condemned Moscow, raising the spectre of a larger Russian-Sunni rift and possible consequences such as renewed Saudi support for jihad inside Russia. This threat might only harden Moscow’s quasi-alliance with Iran and its allies in Damascus.

Perhaps, if the West had not expanded NATO without Russia and against its wishes in the mid-1990s and had made a greater effort at luring Russia into the West by supporting its economic transition to the level it did for new NATO members and others, then the confrontation over Yugoslavia and later Serbia and Libya could have been avoided, Russia might have abandoned its Cold War Syrian ally, and Moscow would now be willing join the West in taking the risks of humanitarian intervention and might have been in a position to temper some of our more idealistic temptations. In this case, if things were to turn out badly in such endeavours, the great powers at least would stand together against the growing Islamist menace. Now, alas, all bets are off.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment