In Italy, civil society is leading the way for integration of the Muslim community.

It’s 33C degrees in Rome. The beaches are already full and the bars are playing loud music serving cold beers. “The problem is not fasting,” says Youssef, a young Moroccan who works as a barman. “The problem is the environment. It is extremely difficult to remain in Ramadan mood while working on a beach.”

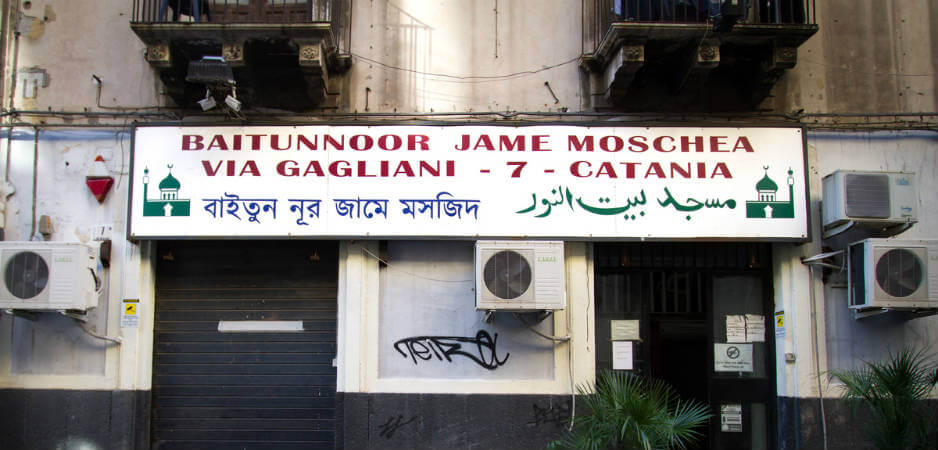

Indeed, being a Muslim in Italy is not an easy task. It is not only the hot weather, the 17-hour-long fast during Ramadan or the most infamous temptations of la dolce vita that make staying devoted difficult. In largely Catholic but secular Italy, Islam is not yet recognized as an official religion. It is a political embarrassment for a European country that is home to almost 2 million Muslims.

“The first official request was made the early 1990s,” explains Mohammed Ben Mohammed, a Tunisian who’s lived in Italy for over 20 years and current president of one the oldest Islamic centers in Rome, Associazione Culturale Islamica in Italia. “It has been over 25 years that we are still waiting.”

Integration

Meanwhile, the Muslim community has been working hard to integrate with the local society. The Islamic center, where Mohammed also serves as imam, for instance, is located in one of the most important suburbs of eastern Rome. In a little over a decade, this working-class corner of the city previously known mainly for its high crime rate has become an important hub for both commercial and social life, and not only of the Arab-Roman community.

Mohammed Ben Mohammed © Elena Hanim Onem

Although the gentrification process is related to many factors, it is significant that the mosque did not result in the creation of an immigrant “ghetto,” as many would have feared. “We are perfectly integrated with the local society,” Mohammed says proudly. “Even after 9/11 we never had the negative reaction from our neighbors. The only problems come from media and politics.”

The public debate around Islam in Italy is, in fact, extremely shallow. When major network channels visit the local mosques, they usually do so only to ask for comments about the latest terrorist attacks in Europe or to question the building violations of informal mosques. Articles and commentary about Islam are mainly relegated to terrorism and women’s rights issues.

This has created not little diffidence, especially from the Muslim immigrant community, which is a large majority. Many avoid making public comments for fear of being misunderstood due to language limitations. Others, however, are quite outspoken.

In Tor Pignattara, a multiethnic area in Rome inhabited mainly by the Bangladeshi community, public events about Islam are not a rarity, especially during Ramadan. One in particular was organized by Dhuumcatu, an association created in the 1992 by Bangladeshi migrants with the aim to improve intercultural dialogue in Rome. The idea of Dhuumcatu was to offer iftar dinner to the neighbors, making Italians more aware of Muslim practices.

It did not pass unnoticed that some of the commari — typical Italian gossipy neighbors — began to eat before sunset, while the Muslims were still waiting. “We know it is more out of naiveté than rudeness,” was the comment. “Events like that are extremely important,” adds Paola, an Italian woman who took her family to eat the offered meal. “Unfortunately, they receive little support and publicity by the local institutions,” she notices.

Since the Time of Mussolini

The official recognition of Islam as a religion would certainly be an important step to implement at an institutional level. Back in the 1920s, Benito Mussolini is reported to have said an absolute “no” to the construction of a mosque in Rome. But it was in fact opened in 1995, and in a very fashionable area. Today, the Mosque of Rome is one of few in Italy, although it is not officially recognized as a mosque, but remains registered as an Islamic cultural center.

Certainly, Italy has changed a lot since Mussolini’s time. Yet, “In 10 months that I am here, I realized that Italians have very little knowledge of Islam,” notices Salah Ramadan Elsayed, the Egyptian imam of the Mosque of Rome who graduated from the prestigious Al-Azhar University in Cairo.

Elsayed studied languages and translation at Sapienza University of Rome and fell in love with the city. Now, he is back in the Italian capital with the difficult task of defeating the widespread prejudice toward Islam. “Many Italians and Europeans are actually very interested in knowing the reality of Islam,” he explains. “I think they perceive there is something wrong about the image they receive in the media, so they come to this Islamic center to find out the truth.”

The mosque is indeed the referent point for the Muslim community in Italy. Its minaret is the only one in the city, and serves as a symbol of Islamic culture, integration and prosperity at the heart of Catholicism. It did not take long before it became part of the city’s life. Not only people interested in Islam come here, but also those who come for the exotic sweets and spices of the Friday market.

Mosque of Rome © Elena Hanim Onem

Now, even this monument appears in a state of decay. The complex had been supported and maintained by wealthy Arab kingdoms, but now the price of Middle Eastern wars, the growing international prejudice and the local economic crisis reached this corner of religious crossroads. Consequently, the notorious Roman nonchalance toward strangers has gone into decline. “I believe it is up to us to make Italians understand a bit more about Islam,” says Mousumi Mridha, who works at Dhuumcatu. “Sometimes when I wear the niqab, I see that many get scared, so I often stop to explain why they shouldn’t be.”

Thus, many Islamic centers are opening their doors during Ramadan, inviting community representatives and institutions to share the iftar moment with the local Muslim community. They also offer donations and meals to the many refugees who find themselves in a foreign country without any support. But, as Imam Elsayed says, speaking on behalf of the Italian Muslim community: “We certainly need to do more.”

An obstacle to the official recognition of Islam in Italy is the lack of interest in Italian politics to find an agreement for integration. Many Muslims, although born in Italy, do not have Italian citizenship due to the constant delay of the ius soli law (“law of the soil”), which would grant Italian citizenship to those born in Italy to foreign parents. As a consequence, political representation and power of influence for raising Muslim concerns on a political level also becomes an issue. Italian political will and Islam find themselves at an impasse.

Grassroots society, however, seems to be a few steps ahead. Every day, in the blocks of the Italian cities and towns, both Muslims and locals are working in the important effort of cultural sharing: “It is when you are not familiar with something that you perceive it as a stranger. This is normal in every society,” explains Mohammed.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: JannHuizenga

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.