In 2018, the President of the United States Donald Trump posted a rather enigmatic tweet about“farm seizures and expropriations and the large scale killing of farmers” by the South African government. What initially seemed puzzling was soon everywhere. A few days later, during the former UK Prime Minister Theresa May’s three-day trip to Africa, right-wing MEP and leader of the Brexit Party Nigel Farage also tweeted about the South African situation and the necessity of “Standing up for white people.” Months earlier, far-right media personality Katie Hopkins was briefly detained as she tried to leave South Africa, having spent a short time there producing a film about the treatment of white farmers.

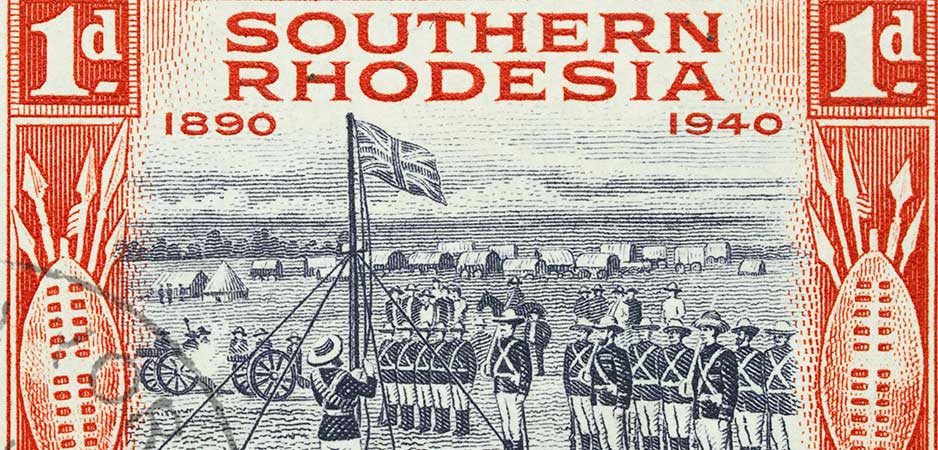

The radical right’s obsession with southern Africa goes back even further. In 2015, the Charleston Post and Courierpublished a photograph of American white supremacist and mass murderer Dylann Roof. In the photo, Roof has two patches on his jacket, one of the flag of apartheid-era South Africa and the other of the flag of Rhodesia. Just last year, during demonstrations in support of far-right activist Tommy Robinson, observers from Hope Note Hate noted the presence of someone wearing a shirt bearing the Rhodesian flag among the crowd supporters.

Racism as an Ideology

This southern African obsession is not new. It has roots that go back to the 1950s and 1960s. These years saw the beginning of the end of European colonialism and attempts by organizations like the UN to tackle racism as an ideology. Based on my own research on the British radical right and its relationship with British imperialism, it is possible to shed light on what southern Africa has historically meant to the radical right. In interrogating their persistent obsession with southern Africa, we can better understand what people like Trump, Hopkins, and terrorists like Roof, mean when they invoke it today.

In the first instance, the postwar movements of the British far right, such as Oswald Mosley’s Union Movement and A. K. Chesterton’s League of Empire Loyalists, found South Africa attractive because its government spat into Harold Macmillan’s “wind of change.” After their victory in the 1948 general election, the Afrikaner National Party came to power and began instituting an intensified system of racial segregation, known as apartheid.

The policy of the South African dominion was very much at odds with post-war Labour and Conservative governments’ aim of a measured, moderate and eventual progress toward multi-racial self-government within its African colonies. The activists and ideologues of the British far right found South Africa’s unapologetically racist stance exhilarating, particularly in a world where fascism was marred by its associations with Nazi Germany.

In Mosley’s case, South Africa functioned as the cornerstone for his plans for a united European recolonization and racial segregation of the African continent. Chesterton, born to British settlers in South Africa shortly before the Boer War, felt a considerable and romantic affinity with its intransigent white settler community and shared their disparaging view of “the African.” For both, South Africa functioned one the one hand as “evidence” of the impossibility of racial mixture and, on the other, as a glowing example of the potentialities of white rule. They credited the white settlers of South Africa and those of the nearby semi-independent British colony of Southern Rhodesia with having carved civilization out a land of savagery.

In the 1960s, as the pace and scale of decolonization increased, and the radical right stepped up its campaigning against Commonwealth immigration, southern Africa acquired a new relevance. The experience of white settlers struggling against African nationalism and British colonial policy provided British radical-right activists with an emotive, metaphorical vocabulary. They employed this in their campaigns against immigration on the streets of Britain, recasting Britons as an endangered racial minority, akin to their southern African “kith and kin.”

Mythical Lands

Increasingly at odds with the newly-independent African and Asian Commonwealth member states, South Africa withdrew and became a republic in 1961. In 1965, Southern Rhodesia, under pressure to extend its voting franchise beyond its white population, unilaterally declared itself independent Rhodesia. The British radical right now denounced the Commonwealth as “coloured,” dominated, they argued, by anti-British world leaders like India’s Jawaharlal Nehru or Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah.

Mosley’s Union Movement, Chesterton’s League and new radical-right groups such as the British National Party and the Greater Britain Movement called for Britain to withdraw from or disband the Commonwealth. To replace the Commonwealth, they proposed an alternative alliance with the “white” nations of South Africa and Rhodesia.

Beyond their historic links to the golden age of British imperialism, for the British radical right, South Africa and Rhodesia functioned as white supremacist Brigadoons, quasi-mythical lands of unimpeded white power. They believed that while Britain had declined, enfeebled by the welfare state and “invaded” by immigrants, South Africa and Rhodesia had remained in a pure, prelapsarian state. For them, the antithesis to the “metropolitan liberal elites” were the colonial underdogs. In idolizing the white settler regimes of southern Africa, the British radical right was also romanticizing the disenfranchisement, violent oppression and murder of people of color.

The history of the radical right demonstrates that we ought to be alert to the dangerous possibility that, when commentators today express “concern” for the plight of white farmers or wear the symbols of these regimes, they in fact are pining after the very same things.

*[The Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right is a partner institution of Fair Observer.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.