A shaky structure and vague promises have seen the light of day following the climate conference in Paris. Chitra Subramaniam explains.

The very talented Swiss artist Patrick Chapatte’s 2006 cartoon to mark the start of the international climate talks in Nairobi in November 2006 could well have been repeated for the recently concluded climate talks in Paris. Nobody is quite sure what was achieved, but everyone is relieved that talks didn’t crash. All the right words are in. The treaty talks of finance and adaptation, damage and loss, stocktaking, technology, emission reduction and market mechanisms, but the sum of the parts has led to more confusion and suspicion, not confidence.

The good news is that the world now has a freshly minted climate change deal where 196 countries have agreed to keep the rise of global temperature well below 2 degrees Celsius by the turn of the century. The mythical Eiffel Tower in Paris lit up with 1.5 degrees spangled across. Leaders also agreed to ensure that their countries would peak their emissions swiftly so that collectively they could ensure that net greenhouse gas emissions would return to zero.

The less good news: The world is no closer to saving itself from the disastrous effects of climate change than it was two weeks ago because the 31-page treaty is low on specifics. For example, it speaks of rolling out $100 billion 2020 onward, but fails to mention what, why and, above all, who should pay. It also has a glaring untruth written all over it: There is no recognition of the historical responsibility for pollution.

So, at the very best, the world has sketched itself a new text on which to pin future hopes and expect early disappointments. At worst, the marathon talks that lasted for two weeks showed bad blood, dishonesty and pressure tactics profiling once again that lack of trust and good faith is the bane of multilateral negotiations and diplomacy.

What is the immediate take-away for India?

There are those who believe that as long as fossil fuels remain the cheapest form of energy, they will be used and for now, coal is India’s best option. But another, more interesting scenario has also emerged from the way many say India strategically and politically prevented the talks from collapsing.

How much of that is true, the future will tell, but New Delhi is within grasping distance of the benefits of swiftly moving away from carbon by playing its large domestic market potential and ambition to grow at double digits. Show us the money and we will show you the market is an interesting spot to be.

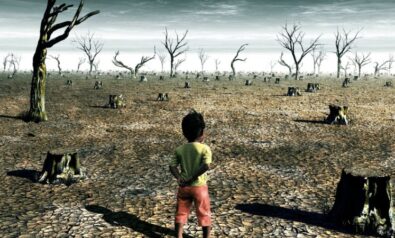

Paris was supposed to end fragility—fragility of poor people, the world’s forest and water resources and food supply chains. Developing countries looked to finance and resources to mitigate damage and adapt to new technologies, so as to not repeat the errors of rich nations.

But here’s the flaw. The new treaty is blind to historical responsibility on which compensation hinges, thus placing all countries on par in their future efforts to prevent global warming. One report predicts that 50% of economic growth between 2010 and 2015 will come from some 440 cities in emerging markets—China, India and Africa.

What will be the role of clean technology in their trajectories, and how can they access, finance or develop this?

The climate treaty is weak on specifics and has no road map—hence it is not a reliable ally. Developing countries also hoped Paris would address rising sea levels, soaring temperatures and increasing pressure on land and water, among other issues. Instead, they returned with a text that says the damage to climate “does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation.” This means that developing countries will have to scrounge around for their right to assistance in a spirit of unhealthy competition and suspicion.

Is All Lost?

The other problem profiled in Paris was science and what role it was to play to influence policymakers, industrialists, civil society and lawmakers. While 2 degrees Celsius was bandied about months before the final negotiations, a straight cause and effect relationship between carbon emissions and future global warming remains elusive. In fact, the relationship is imprecise, leading to fears that this will further dilute any talk of compensation and liability.

The cruelest cut for developing countries was perhaps the fact that the failure to pin compensation was seen as a means to not address the issue at all. For all the back thumping and table pounding in Paris, little action is expected before 2020. Plenty of opportunities exist for governments to change the text and for national parliaments to not ratify any or all of the commitments.

What next?

All is not lost. There is now a super-structure available to the world to work on. As climate change continues to worsen and affects millions of lives, it is people who will now be demanding action of their governments. The pollution in Delhi and the floods in Chennai and the resultant public anger is where hope lies. Voters will increasingly force governments to come up with solutions in the true spirit of democracy and transparency.

As for the United Nations, the most important question it needs to answer as it turns 70 is this: If the comity of nations cannot come to a common understanding about what are human rights, how can it give itself the power to police the world’s resources?

If only the polar bear could speak and the world’s poor would be heard, what would they say?

*[This article was originally published by The News Minute.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Frederic Legrand – COMEO / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.