The challenges of building a Macedonian national identity

Welcome to Skopje – where monuments are our pets! This is not the tagline to Macedonia's new CNN advert, but a tweet in response to the Skopje 2014 architectural project, by the aptly-named Citizen of the World. This project aims to bring Skopje into the 21st century with a host of new buildings, including a new National Theatre and a Jewish Museum. But the scheme has proved controversial as monuments have been popping up like mushrooms all over the city centre, including a 22 m high bronze of Alexander the Great and a statue of his father, Philip II of Macedon. Other comments from social media compiled by the local online service ‘Okno’ include questions such as whether there would also be a Chuck Norris statue, and if the Roma district of Skopje ’Šuto Orizari’ will receive any monuments. Several of Skopje’s ‘twitterati’ have commented that the official Skopje 2014 presentation video bears a striking resemblance to several popular computer games currently on the market.

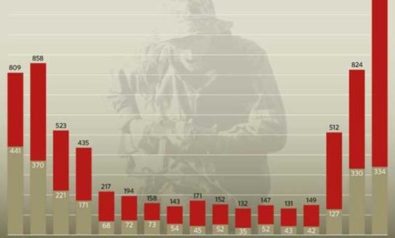

The project was first presented in 2010. The country was then, and still is ruled by a coalition dominated by the VMRO-DPMNE (Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation – Democratic Party for National Unity) party, led by the Prime Minister Nicola Gruevski. The main criticisms the ruling coalition is facing are the spiralling costs of the project, the lack of consultation, and the legitimacy of spending so much on monuments in a country with an unemployment rate of over 30%.

Skopje 2014 is a divisive issue in Macedonia, with some vehemently against it, others strongly in favour. Populist policies are often seen as a danger to democracy, precisely because they polarise debate and push people to extreme positions. So, is Skopje 2014 a populist dinosaur, and if it is, what are the driving forces behind it?

Constructing a National Identity

If we accept that the Macedonian government is, brick-by-brick, monument-by-monument, trying to build a modern national identity – then what lies behind this? Why is the issue of national identity important right now? In 2008 Greece blocked Macedonia’s bid to join NATO, and in 2009 they blocked E.U. accession talks. The main thrust of Greece’s argument is that the constitutional name of Macedonia, the Republic of Macedonia, implies a territorial claim on the neighbouring Greek province carrying the same name. But it is not clear on what basis this claim is being made and it is hard to imagine how Macedonia could even construct a territorial claim against Greece. Let’s look at a clear example of the gulf between Macedonia and Greece, an economic David vs. Goliath. In 2009, Macedonia’s total GDP was just over 9.3 billion dollars. In the same year, the Greek government’s military expenditure alone came to just over 10.5 billion.

Moreover, in 1992, an amendment to Macedonia’s constitution came into force, which states that “The Republic of Macedonia has no territorial pretensions towards any neighbouring state.” Where the Greeks do have a reason for complaint is the series of actions and policies taken which have displayed nationalist sentiment, such as the renaming of the airport from “Petrovec” to “Aleksandar Veliki” (Alexander the Great) in 2007. But these are symptoms of a problem, not causes. The Greeks can accuse the Macedonian government of stupidity, but not of malice.

There is also one major difference between Slavic Macedonian identity, and Greek Macedonian identity. That is, for the Greek Macedonians, their Macedonian identity is only part of their identity, as they are also Greek. But for Slavic Macedonians, they have no other over-arching identity. Moreover, their identity is not only threatened by Greece, but also by their eastern neighbour Bulgaria, which does not recognise Macedonia as having a distinct identity or language. As a 2009 International Crisis Group report states, “For Macedonians, calling into question their identity is linked to the survival of their country. They fear that, at root, many Greeks and others in the region challenge the long-term viability of their state, with its internal tensions between ethnic Macedonians and ethnic Albanians.”

Consequently, the challenging of Macedonian national identity provides the background to the populist policies from 2010 to 2014, the shelf life of the Skopje 2014 project.

European Purgatory and Abuses of Power

This then raises the question, why is the Macedonian government intent on completing such a project which it knows will anger the Greeks, and divide its own citizens? To some extent, it suits the ruling party to be in limbo, in European purgatory. They do not have to take responsibility for their actions, as an easy scapegoat is at hand. They do not have to deal seriously with difficult issues such as unemployment, corruption, media freedom, or the full implementation of the Ochrid peace accord which ended an internal conflict between local Albanians and Macedonian security services in 2001. The intransigence of Greece and the apparent unwillingness of international institutions to stand up for Macedonia also turn public opinion against the EU and international organisations. Perhaps most importantly, this dividing of citizens prevents the formation of a strong civil society, which might cut through ethnic and nationalist lines.

Alarmingly, along with the rise in populist policies, there have also been signs that the VMRO-DPMNE-dominated government is seeking to limit press freedom and in turn, silence its critics. In July 2011, three daily newspapers were forced to close allegedly due to unpaid taxes, leading to the loss of 150 journalist positions. Parliament also passed amendments relating to the Broadcasting Council, which increased the influence of the ruling party. The wages of journalists are precariously low and so the temptation to accept bribes is strong. On March 14th 2012, Velija Ramkovski, former owner of A1 television station was sentenced to 13 years in prison for tax evasion and other charges (one of the strangest accusations was that he was running an illicit biscuit factory from the basement of the TV station). Critics say that Ramkovski was only charged after A1 became critical of the government. The Vienna-based SEEMO, South East Europe Media Organisation, issued a report in 2011 on media freedom in Macedonia. The report states that as a result of these and other changes “The country’s media landscape was no longer pluralistic.” If the people of Macedonia do not have access to a free and independent press, then the government can act with relative impunity, and any emergent civil society will be pushed to the margins.

Therefore, the driving forces behind the populism of Skopje 2014 are continuing Greek belligerence and the Macedonian government’s disdain for its own citizens.

How Fuzzy is Populism? A Framework

But what exactly is populism? Is it the same as nationalism? The two are often confused, but can we separate them? Let’s take an example. If we look at economics, economic populism would be a policy like raising the minimum wage, or taxing the 1%. Economic nationalism would be ‘Buy French cars!’, or erecting tariffs against imported goods to protect domestic firms. With populism, the audience is ‘fuzzy’ – it is an idealized group of people, a group of workers, the ‘99%’. With nationalism, the target audience is clearer – the nation. One other important definition of populism comes from Peter Worsley, who says that “populism is better regarded as an emphasis, a dimension of political culture in general, not simply as a particular kind of overall ideological system or type of organisation.” Regarding populism both as a kind of dimension of political culture, and as a mood might help us to understand populist policies such as Skopje 2014 and their appeal. It’s also important to remember that populism can come from both the right and the left, and has no political or ideological home. It is, in Kafka’s words, “a cage in search of a bird”.

Who’s Afraid of Populism?

How many Americans can quote a few lines from the US constitution? Most of them, if not all, I would say. How many Europeans can quote from the Treaty of Rome? Even though the Treaty of Rome is the founding document of the EEC (eventually to become the EU), it is not part of any mythology or narrative, it just stands as a legal agreement. Yet if we look at the US constitution, it is not only a legal agreement, but part of a popular, shared social history. Every week we hear from politicians and pundits that there is a ’new wave’ of populism spreading across Europe, from the National Front in France to Chrysi Avgi in Greece. This is scare-mongering, for the reality is that people are voting for new parties because no-one is listening to them. It is easy to be pro-European when times are good, but when times are tough what is there to sustain a belief in Europe?

Populism exists – as a mood, as a dimension, as a way of communicating. But if populism is merely a mood, a dimension, or a tool, then why can’t the EU use it to achieve its own goals? After over twenty years of transition, it should be apparent that the tools needed to bring the Central European and Baltic countries into Europe are not the same as needed now in the Western Balkans. Countries of the Western Balkans feel trapped in the “Desert of Transition”, which makes them more open to populist appeals. As Judy Dempsey stated in a recent piece for Carnegie Europe, “It’s Time for European leaders to Take to the Road”, European leaders need to engage more with real people.

Conclusion

At the heart of the matter is the issue of a small land-locked country that would like to be recognised internationally as a nation state, with a name of its own choosing. The populist policies of the current Macedonian government are caused by the denial of this wish by Greece, its more powerful southern neighbour. Of course, the Macedonian government should realise that the real potential of the country lies with its people, their warmth, humour and talents, not in concrete. But for Greece to use a veto against a smaller country without a coherent argument in fact is not justifiable.

Finally, to paraphrase Isaiah Berlin, the fox knows many things, the hedgehog only one. Populism is cunning; it has many faces, and many ways of operating. This is its strength. Unless the EU finds a way to both understand and harness populist energy, it risks losing the support of people both in Macedonia, and in the entire region.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment