More than two decades after the fall of the USSR many of its former republics failed to establish a democratic and open media landscape, ranking among the worst in media freedom indexes.

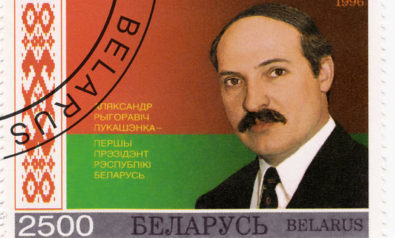

At a Minsk café on a blustery day just before New Year’s in 2010, Franak Viačorka hesitated before switching on his phone. The former journalism student was on the run from the Belarusian authorities for organizing and blogging on antigovernment demonstrations that erupted after the disputed December 19 presidential vote that saw the reelection of the man who had occupied the seat for the previous 16 years, President Aleksandr Lukashenko.

Viačorka called his father on Skype via his cell phone’s mobile web service, and within minutes KGB agents descended on the café to arrest him and his two friends, having located them as soon as he logged on. Over the course of the next several weeks he was repeatedly threatened and intimidated while in custody. Viačorka was eventually released, and is now a journalist with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL).

He, like other journalists working in countries that censor free speech, recognizes that today’s digital media landscape represents opportunities and threats both for the journalists trying to expand the limits of free speech and for the regimes intent on restricting them. RFE/RL journalists operating in the former Soviet Union are often targets of these attacks because of the work they do, but they are also at the vanguard of technologies that can circumvent the censors.

Russia often makes headlines for its poor rankings in surveys of media freedom, but what is less publicized is that, with the exception of the Baltic States, the situation in the rest of the former Soviet Union is hardly more encouraging.

Azerbaijan

The Reporters without borders 2013 Press Freedom Index ranks Azerbaijan, for example, at 156 out of 179 countries, below Russia’s 148 standing. The tiny, oil-rich country on the Caspian Sea has a shocking record of jailing and harassing activists and journalists. In the last few years, the security apparatus has used Internet and social media in attempts to discredit journalists who step out of line, especially those who report on official corruption. They publish personal information obtained either by deception and invasion of privacy, or simply fabricate the stories completely.

In March, 2012 Khadija Ismayilova, a freelancer for RFE/RL who has built a reputation in Azerbaijan as a fearless reporter and has been internationally recognized for her investigations into the financial activities of President Ilham Aliyev and his family, was targeted in a blackmail campaign that was perpetrated in state-run newspapers and online.

The campaign began when Ismayilova received an envelope in the mail containing photos of a personal nature that were later discovered to be stills from a video camera hidden in her apartment. The photos were accompanied by a note that said, "Whore, behave. Or you will be defamed."

Ismayilova went public with the blackmail attempt on her Facebook page, writing, "I am convinced and determined that I can withstand any blackmail campaign against me. This is not the first time that these acts of blackmail have been used against fellow journalists.” She then appealed directly to the president of Azerbaijan to investigate these events and provide protection to ensure her security.

There was no official investigation, no protection provided by the authorities, and video from the hidden camera was later posted on Facebook and several other phony websites created to imitate well-known news sources.

In another incident, reporter Yafez Hasanov was harassed as a result of his reports investigating the 2011 death of a man named Turac Zeynalov who died in the custody of Azerbaijan's Ministry of National Security. Hasanov had first been detained in connection with the case when he was pulled into an unmarked car and given a warning following a meeting with the victim’s family in Naxicivan.

Hasanov then began receiving text messages and calls from unidentified persons threatening reprisals against him and his family if he did not stop reporting. In one text he was warned, "you'll end up like Zeynalov." In one phone call he was told, “if you do not stop [reporting], you’ll be shocked by what you see.” Hasanov changed his phone number, but the calls continued.

In an incident recalling previous smear campaigns against other independent journalists in Azerbaijan, obscene blog posts soon appeared accusing Hasanov of having intimate relations with several women.

Though often harassed, threatened and followed, independent journalists are able to operate openly in Azerbaijan, which is not the case in some other countries in the region.

Uzbekistan

The Central Asian republic of Uzbekistan became a no-go zone for journalists, including RFE/RL reporters, and human rights defenders in 2005. They were expelled or shut down after reporting on the Andijan massacre in May that year, when several hundred demonstrators were gunned down and allegedly buried in mass graves by the Interior Ministry and National Security Service.

Absent journalists on the ground, RFE/RL maintains informal networks of contacts inside the country and increasingly benefits from the contributions of citizen journalists to gather the news. As for delivery, RFE/RL has learned to innovate to stay a step ahead of Uzbekistan’s rigid censorship regime.

RFE/RL’s Uzbek language service’s website is completely blocked in Uzbekistan, so the service has turned to proxy servers and continually educates users about how to safely access the site. Since Uzbek police patrol Internet cafes and monitor the customers’ screens for banned websites, the service has launched a powerful presence on mobile web, to allow readers to access uncensored and in-depth reporting from almost anywhere.

On the other hand, RFE/RL has recently identified an attempt to establish a mirror website crudely designed to imitate the Uzbek service’s website, and RFE/RL’s Belarusian website was the target of a similar attempt following the disputed 2010 presidential elections.

Turkmenistan

Uzbekistan’s neighbor to the south is equally inhospitable for journalists. Turkmenistan has the second-worst ranking besting on North Korea in Freedom House’s 2012 Freedom of the Press report and has numbered among the "Worst of the Worst" countries for freedom overall in the monitoring group's surveys of the last several years.

A recent report by the Committee to Protect Journalists looks for hope in the country's media law passed on January 4, but finds that "reform appears to be only posturing and the most repressive and hermetic country in Eurasia remains just that."

Like other foreign media, RFE/RL is not authorized to have a bureau inside the country, and so in addition to maintaining a network of stringers and contacts in Turkmenistan who provide reports, the Turkmen service has had to exploit online tools to their full extent in order to deliver the news. Their power has yielded two results: the service's website, in particular, has demonstrated impressive growth in the last year, with total visits up 85 percent from 12 months ago, and 50,000 visits and 137,000 page views in January 2013.

Russia

Russia, for its part, no longer sets the paradigm for repression in its neighborhood, but instead, has fallen behind other former Soviet republics in cyber censorship. Though Russian authorities make forays into the realm of internet censorship and online smear campaigns against journalists, their attempts to use the Internet tosilence reporters have so far been largely unsuccessful.

An internet blacklist law that came into effect in November 2012 has caused some concern, however. The law requires Roskomnadzor, the state’s media monitoring agency, to maintain a list of websites that should be blocked due to child pornography, content promoting drug use, and information judged to facilitatesuicide. The law allows any site to be blocked by court order, and the vagueness of itswording and intent has some worried it could be used to target online journalists,irreverent websites, and bloggers critical of the Kremlin. Despite what the new law may portend, so far it hasn’t been implemented as feared.

Evidence abounds that Internet and social media have lowered the barriers for information exchange and civic engagement. At the same time, regimes hostile to open societies and free speech have appropriated Internet tools to advance their own ends, making it more imperative than ever that news providers stay vigilant, embrace innovation, and are first to new media’s frontiers.

RFE/RL's mission is to promote democratic values and institutions by reporting the news in 28 languages and 21 countries where a free press is banned by the government or not fully established.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment

“day just before New Year’s in 2010”

“and within minutes KGB agents descended on the café to arrest him and his two friends”

The author is unaware of the fact that KGB ceased to exist by 2010.

The whole article is a pure figment of the author’s imagination, thereupon. Everything in it sounds fanciful and a clever work of fiction, devoid of any clear and verifiable facts — especially for an author who cannot even verify the existence and/or demise of KGB and USSR by 2010, this is a nice piece of fiction and imagination at best.

Shame on FairObserver to publish such articles on its forum, and thus reducing its own credibility and integrity, and also makes educated readers wonder and doubt about the quality of all the articles on the site.

Letting such lies being published on Fair-Observer makes it seem more like UnFair-Blind.

———

Dear CCR,

I hope you noticed that the KGB agents mentioned in the article operate in Minsk, Belarus. By claiming yourself to be an ‘educated reader’, I am surprised that you are unaware of the fact that the Belarusian security services have retained the acronym KGB. Your time would have been better spent in doing a basic fact check instead of accusing our writers and editorial team of incompetence. Just in case you still have doubts: http://blog.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2014/09/05/belarus_kgb_attacks_ice_bucket_challenge.

As our editorial policy dictates, if you disagree with anything we publish, please send us an alternative. For further information, please visit: https://www.fairobserver.com/contribute.

With best wishes,

Anna Pivovarchuk, Culture Editor