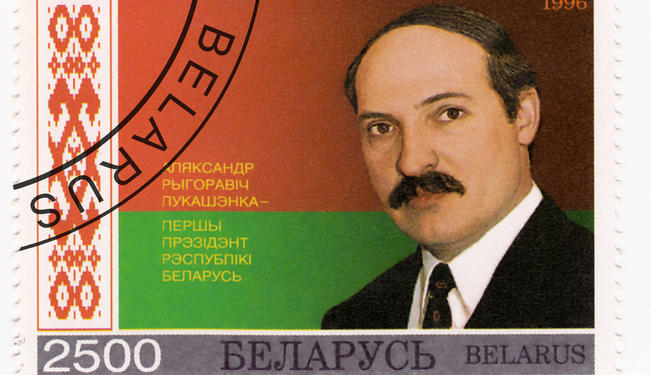

In her interview with Anna Pivovarchuk, award-winning journalist Natalia Radina talks about the assault against the free press in Aleksander Lukashenko’s Belarus.

Anna Pivovarchuk: In 2011 you received the CPJ International Press Freedom Award for you coverage of the protests that followed Aleksander Lukashenko’s ‘victory’. Could you tell us about the events of December 2010?

Natalia Radina: Of course there was no ‘victory’, but just another case of rigged elections. Practically all elections held in Belarus under Lukashenko – almost 20 years – were not recognised by the international community as either free or just. Aside from that, Belarus became famous by setting a sad record by arresting all presidential candidates aside from Lukashenko, as well as their campaign managers, famous journalists – basically all of the country’s elite ended up in prison, just like Stalin’s purges in 1937. I was also arrested and ended up in the KGB prison, where I was charged with organising mass protests and threatened with a 15-year prison sentence.

Pivovarchuk: I wanted to ask you a little bit more about your time in prison. I know that you were threatened – tell us more about the interrogations and what was demanded of you?

Radina: First of all they wanted statements against the presidential candidates, in order to ‘prove’ that they were involved in organising the protests. This was a complete lie as that day the secret services carried out a provocation that resulted in mass arrests.

I can tell you about the conditions in prison: everything was done to pressure you. Men were tortured and beaten, women – including myself – were held in conditions that were comparable to torture. I was held in a cell without a bed, it was a very cold January, I slept on the wooden floor. There was no toilet – you were escorted to the bathroom every four hours – as a result of which I simply stopped drinking water, which undermined my health. It was freezing cold in the cell, only cold water in the tap. There was a complete information blackout; we did not get any letters from our families, we didn’t know what was going on outside – the TV was taken away, there were no independent newspapers, just constant interrogations that went on into the night. These were quite intensive, as many as four a day. We were not allowed lawyers, despite our demands – so we were questioned at the prison without counsel. We were pressured and blackmailed. I was told that when I get out in five years’ time – which is the minimum I would get for doing my job as the editor-in-chief of Charter 97 – my health will be affected, I will not be able to have children. They knew that my mother is an old woman, who has health issues, and kept reminding me that she won’t live long enough to see my release.

Pivovarchuk: It is a horrible story. It is hard to imagine that this is happening in Europe.

Radina: It is hard to believe. When I finally managed to escape to Lithuania, German journalists wanted to record my interview at the KGB museum in Vilnus. When I went down into the prison, which is located in the basement, I could not hold back tears because this museum looks exactly like the prison I was held in, both built during Stalin’s times, and I can say that the conditions haven’t changed at all. Except that in Lithuania it’s a museum, but in Belarus it is an active prison. And it wasn’t even the worst one, there are much harsher prisons. Basically, the prison system in Belarus is on the level of Stalinist times, and their methods are the same.

Pivovarchuk: I can’t believe that they kept the KGB name – as if they wanted to keep it as a reminder of the Stalinist regime.

Radina: Well, yes, it can be said that the regime is neo-Stalinist in nature.

Pivovarchuk: I wanted to ask about your escape into Russia, before you went on to Lithuania. Tell us about that.

Radina: The escape was being planned for a long time – it took me long to decide to do it, because it was dangerous. I was held under house arrest: every day either the police or KGB agents would come and checked if I was home, so the opportunity to flee arose when I was called to an interrogation in Minsk. I was followed onto the train and I can tell I was being watched. I got off the train at night, pretending to buy a Coke, it was 1 am, most passengers were already asleep. I managed to get to a getaway car where my friends were waiting. For a few days I was hiding in Belarus, without any contact with anyone. When after a few days the attention to my case dropped a little, I managed to cross the Russian border, lying in the backseat of the car. I have dyed my hair, trying to change my appearance. I was incredibly scared. Why Russia? Because my passport was being held by the KGB, and Russia and Belarus don’t have a visa regime so there was a chance that the car won’t be stopped at the crossing.

I was hiding out in Moscow for four months. Of course I was hiding the fact that I was in Moscow because if I openly announced that I was in Russia, the government would have had to turn me over to Belarus to honour the union agreement. Thankfully that didn’t happen. I applied to the Office of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). I was helped by a Russian human rights activist Svetlana Galushkina. The US State Department EU were notified of my case and because they lobbied my case, the UN resolved it relatively quickly and I received a refugee status within four months.

Pivovarchuk: So the Russian government did not try and stop you?

Radina: No, by the time I turned to the Russian authorities for my exit visa, my case was already approved by the UN and so Russia really did not want an international scandal, so it had nothing left to do but help.

Pivovarchuk: What is the situation in Belarus now? I know that journalists are still being threatened – the surreal story of Irina Khalip, the Minsk correspondent for Novaya Gazeta who was given a two year suspended sentence, was threatened that her children would be taken away – and that chicken head she found in the mail box. How often do such things happen now?

Radina: Journalists now are not in jail but rather under constant surveillance. Irina Khalip is practically under house arrest right now, she is not allowed to leave her home after 10 pm – so she can’t even go to their country house for the day for fear she might not make it back on time for the security check. Andrzej Poczobut, a Polish journalist is also being kept in the same conditions following a suspended sentence, and he is also not allowed to leave the country while another case is being prepared against him – if he is convicted, he might end up in jail.

Photojournalist Anton Suryapin spent a month in prison for the pictures of teddy bears airlifted by a Swedish NGO – the case against him is on-going, he is awaiting trial – so of course these conditions are very far from ‘free’ for a journalist.

I cannot go back to Belarus as I have no idea how many criminal charges have been filed against me by this time. So of course there is no media freedom. There are constant attempts to frighten and threaten journalists by the special forces – they use the same methods as you mentioned with the chicken head: phone calls, letters. Even I receive those, abroad. There is no freedom of speech in Belarus. It has been under constant attack for the past 20 years and right now there are practically no sources of independent information in the country.

Pivovarchuk: Aside from threats, what else does the government do to try and curb your activities? What difficulties does Charter 97 face?

Radina: Well, first of all, journalists are being killed. In 2000, Dmitry Zavadsky, a cameraman, was killed. Veronika Cherkasova, a journalist for Solidarnost’ was killed in 2004, and in 2010 Oleg Bebenin – the founder of Charter 97 – was found dead. This happened three months before the elections, the government claimed it was suicide, but none of us believe this version of events because right before his death Oleg Bebenin agreed to become the chair of the election committee for the opposition candidate Andrey Sannikov. Sannikov has now received asylum in the UK, and was the most promising of the opposition candidates and would have made it to the second round against Lukashenko if votes really had been counted – so this was a direct attempt to frighten Sannikov and his team.

The site itself – our experience is exemplary of what can be done against journalists. First of all, as all the TV channels were transferred under government control, the opposition was not allowed airtime. Then independent radio stations were closed down, then one after the other independent newspapers followed. Slowly, the only source of independent information was found on the internet. There are not many ways, aside from the Chinese tactic of blocking unwanted sites, to shut journalists up on the internet, the authorities turned to brutal methods. For example, in 2010 a number of criminal charges were brought against our site for articles published against certain officials, searches were conducted in our offices. These were quite violent; during the first search I was beaten as they forced their way into the office. They confiscated equipment, without any charges, and within a year they took away 20 computers – at time we thought we will have nothing to work and write on. Then, within a year we faced three court cases, then Oleg Bebenin was killed, and then I was arrested.

Pivovarchuk: Russia has recently seen an increase in anti-demonstration laws, laws against NGOs and other attempts to curb dissent…

Radina: Yes, Russia is moving in the same direction as Belarus. When I hear Russian democrats telling me what is going on, I say, ‘Just you wait, it will get worse’. … Putin is observing the situation in Belarus with interest, that the people can be intimidated through the increase in the use of force and saw the reaction of the West – that the West cannot do anything against a dictator in the heart of Europe. Of course this encourages what is going on in Russia, because Putin understands that Russia is much bigger, with a nuclear arsenal, and he know he will remain unpunished if a farmer like Lukashenko is getting way with it.

Pivovarchuk: What do you think is the future for Belarus? How do the people see the situation? Do you see any chance for change?

Radina: In order to defeat the regime we need international support. Without this support it might not be impossible, but very difficult to change anything. Today the dictatorship exists thanks to the EU, which continues to buy Belorussian oil that has been made out of cheap Russian crude. The oil products and fertiliser are the main source of foreign currency in the country and this business is controlled directly by the regime and the KGB. The money that is derived from these exports is channelled towards the maintenance of the repressive apparatus. We have called on the EU to introduce tougher sanctions, such as the United States already has put in place. But these have not had much result as human rights don’t concern the EU as much as the cargo that leaves the Belorussian ports. But the situation can change any minute as the financial crisis continues. Recent estimates show that up to 2m Belorussians have left the country to find work elsewhere; 2.5m out of 9.5m working citizens are not part of the economy – so people are leaving to Russia and Europe because you cannot feed a family working in Belarus today, with high prices and destitute wages. There have been a few laws issued where workers cannot be fired from certain factories, but this spring can shoot out at any moment and as history shows dictatorships eventually collapse.

The international community must understand that if it put even a minimal effort the situation could be changed very easily. Lukashenko today is weaker than ever, and that needs to be understood.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment