Hollande’s approach to Syria has done more harm than good to France and the Syrian people.

While there has been much debate within the international community over what should be done in Syria, France has adopted a more assertive, if not aggressive, position. From the very beginning of the Syrian conflict, the French government was the first to recognize the Syrian National Coalition in November 2012. It was also the first government to promise arms to the rebels.

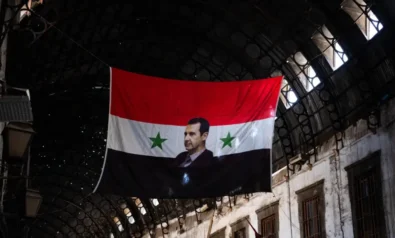

Later, French President François Hollande pushed for a military strike on Syria to “punish” the Assad regime, while most of his European counterparts remained very skeptical of such an intervention. Nonetheless, the French government finally decided not to deliver arms to the insurgents. Following the US-Russian deal on Syria’s chemical weapons in September 2013, the idea of a military intervention was abandoned.

Meanwhile, in Africa, France launched a military intervention in Mali in January 2013 and has been involved in the Central African Republic since December 2013.

To many, French foreign policy seems to be quite messy and inconsistent. However, there are very rational explanations behind it that can justify these mixed foreign policy decisions. France’s strategy in Syria — and elsewhere — has been shaped by long-standing and well-identified interests.

Nonetheless, by promoting France’s interests, President Hollande has probably done more harm than good to his own country as well as to Europe and, above all, the Syrian people.

Drivers of French Foreign Policy

France’s strategy in Syria has been defined according to a set of three key drivers. The first is related to French interests in the Middle East. Following its colonial legacy and historical tradition, France has always conducted, especially since Charles de Gaulle’s time in office, a pro-active policy toward Arab states. The French “Arab policy” has taken the form of economic, military and diplomatic relations with Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, Libya, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and, more recently, Qatar.

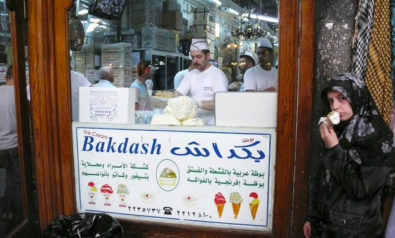

Thus, what has sometimes been called France’s “aggressive” policy on Syria is nothing but a reflection of its well-established interests in the region. France has certain economic interests in Syria; before the war, it also expected to use the country as a “hub” for oil and gas transit.

In addition to that, France has deep geostrategic interests in neighboring Lebanon. Since the end of the mandate period in the 1930s, Paris has constantly sought to maintain and develop strong diplomatic and cultural ties with Lebanon in order to establish its influence in the region.

Lastly, Syria takes on a prominent geostrategic dimension, especially in respect to its role within the Russian-Iranian axis. Indeed, the three countries share a common interest in counterbalancing Western powers on the world stage. They have been developing a strong relationship for the last decade. France’s influence and interests in the Middle East are threatened by this new geopolitical axis.

This explains why the French government was initially willing to deliver arms to rebels in Syria. It eventually backed down for three reasons. First, French experts feared the delivery of arms would trigger a flare-up in the entire region. The Libyan experience had already proven that it was really hard to control arms flows after their delivery. Second, following the stagnation of the conflict, it became unclear whether arms would benefit the “right” opposition groups or the jihadists, against which France has been fighting for the last decade. Third, France was forced to abandon its project due to the reticence of the international community.

A second driver of France’s foreign policy is its desire to be recognized as a global power. While such a claim was relevant under de Gaulle and even before his time, the role of France on the international stage has become unclear since then.

A subsequent priority for French leaders was and still is to guarantee France’s independence in decision-making. This explains why France had been so assertive in promoting a military strike against the Syrian government. It wanted to show that it could take the initiative on matters as important as the Syrian crisis. Paris had to step back eventually.

Once again, domestic tensions arose as the possibility of another military intervention was mentioned. Further, the compromise found by Russia and the US regarding a deal on Syria’s chemical weapons made a military intervention obsolete.

External factors are not the only elements that have shaped Hollande’s strategy in Syria. Logically, the foreign policy of any given country, and France makes no exception, is intrinsically connected to, if not determined by, the situation at the domestic level.

Ever since Hollande became president in 2012, he has faced growing challenges at home, especially regarding the economic situation. Despite the measures he took, unemployment remains high and economic growth has barely recovered. He has not been able to satisfy neither the left-wing, which sees him as having reneged on his electoral promises, nor the right-wing, which blames him for not going far enough. Overall, Hollande is often depicted as ineffective, not to say feeble.

This explains France’s current policy in Syria in three ways. First, by focusing on serious issues abroad, Hollande attempts to distract from the problems at home. Second, the idea that France has a significant role to play in international affairs enjoys a great national consensus. Third, for Hollande, being a hawk on the international stage clears himself of being too soft on the domestic scene and gives him a bit more legitimacy and credibility.

Thus, France’s policy toward Syria is not irrational. It is the result of political and geopolitical calculations coupled with domestic considerations. Yet whether this strategy has been successful is much more debatable. In fact, the main issue is that President Hollande has been far too gung-ho to deal with the Syrian crisis. This has not been without consequences.

Hollande’s Gung-Ho Strategy

France’s strategy in Syria has had several boomerang effects. To begin with, recent events have shown that France does not have the political means, nor the material capacity to play by its own rules. While Hollande was ready to launch a military strike in August 2013, US President Barack Obama stepped back and waited for the approval of Congress.

Hollande found himself in a very embarrassing situation. This event exemplified France’s dependency on the US. In other words, it seems that without the support of Washington, or at least of some of its allies, France is unable to influence the course of international affairs.

Moreover, the question was finally solved by the US-Russian deal on Syria’s chemical weapons. For most of the international community, the deal represented a good compromise between a potentially damaging military intervention and the human costs of a “doing-nothing” policy.

However, for the French government, the situation was particularly humiliating since it did not take part in the negotiations. Thus, this event not only revealed France’s lack of influence on the international stage, but also showed that the international community could merely do without it.

Overall, the way the French government dealt with the entire crisis contributed to its de-legitimization. The fact that the French president was ready to launch a military strike without seeking parliamentary consent was seen as highly undemocratic. Besides, President Hollande did not appear to give much credit to international law when he declared that it “must evolve with the times” rather than being a constraint to a military intervention.

By bypassing both principles of democracy and legality, France deeply damaged its credibility. In sum, the way the French government has managed the Syrian crisis has only succeeded in deepening its marginalization on the international scene.

France’s strategy toward Syria has also negatively impacted Europe. Hollande’s assertive policy has exemplified the existing dissensions between European partners. On the question of arming the rebels, Germany, Sweden and Austria had always been very cautious and disapproved of French — and British — rushed statements about the need to help the insurgency fight back against the Assad regime. Likewise, the Germans and Italians were very critical of France’s military activism. The Italians feared the French warmongers would threaten the security of European troops in Lebanon.

While France has justified its policy regarding the need to protect the Syrian population, one must not forget that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Ultimately, the Syrian people have been the very first victim of France’s ineffective strategy in their country.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment

clotilde’s analysis is not kind with Hollande’s foreign policy in Syria. But it tells the truth. France faces a double crisis : international and domestic but “king” Hollande desesperatly try to follow de Gaulle and Mitterand. he is the wrong man in a complex and volatile situation. It is clear that 5th Republic institutions are defintely not adapted to the 21st century challenges. In my opinion, following Clotilde’s analysis, France must admit that it has to be more democratic inside through a better consideration for its parliament. It must also admit that outside France, the neo Gaullian policy of national independency does notnmake sense in our globalized world.