A financial transaction tax might help regulate high frequency and derivative trading. This is a rebuttal to a previous article which was skeptical of the so-called Tobin tax.

Partially adapted from: A General Financial Transaction Tax: Strong Pros, Weak Cons, Stephan Schulmeister. Intereconomics, Review of European Economic Policy, 47 (2), March/April 2012.

The assumption that asset markets are basically efficient has become increasingly questionable in the past three decades. Deregulation – notably the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act of 1999 – has allowed financial innovators to trade an ever more diverse set of assets, and at a much higher overall frequency (partially enabled by electronic platforms). Yet the financial sector has not improved its core functions; interest rates are no more generous to borrowers and risk is not better managed. Meanwhile, the past decade has seen pronounced bull and bear cycles. In this context, the Financial Transactions Tax (FTT) is a useful regulatory tool.

Today’s FTT proposals are primarily aimed at high frequency trading. Much of this trading is based purely on momentum. Essentially, short-term price trends (based on intraday data) are strengthened by the use of automated trading systems and accumulate to medium-term trends – which, in turn, are reinforced by trading systems based on daily data. This results in a systematic overshooting of exchange rates, commodity prices, interest rates, and stock prices in both the short and long term. This misalignment with market values, even if temporary, favours rent-seeking activities of financial investors/speculators and impedes entrepreneurial activities.

How might a tax punish the guilty (i.e., derivative traders and hedge funds) while sparing the innocent? First, define the scope to exclude dividends, stock or debt issuances, and the settling of trade accounts. And second, set the rate so low that it is immaterial to “real-world transactions.” For instance, were the tax set at 0.05% of the value of the asset (split between the buyer and the seller), an investor purchasing $10,000 of stocks on the spot market would pay a tax of just $2.50. Even hedgers are relatively safe, as they usually hold the derivative – not trade it.

However, the tax would create a deterrent to very fast, leveraged transactions – particularly those with a cascading effect that triggers multiple applications. Imagine a hedge fund using a fast automated trading system to follow trends based on high-frequency data. The system changes open positions of $10mn, on average 50 times a day. Since each change requires two transactions (one to close the former position and one for opening a new one), the fund’s daily transaction volume is $1bn, resulting in an FTT of $250,000 at 0.05%. Thus, the FTT renders high frequency trading unprofitable.

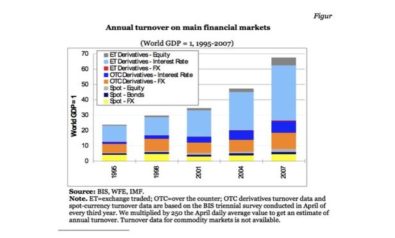

The tax would also curb derivative trading, deregulation’s ugliest offspring. As many commentators have noted, the current nominal value of derivative trades exceeds world GDP by a factor of about 70. This represents a three-fold increase since 1995. (Note: defenders of derivatives would note that the net value is much lower as financial institutions manage risk by offsetting exposures against each other. But derivative contracts no longer need to hedge against a real position following further legislation in 2000.)

While the FTT would likely decrease overall trading by about 70%, concerns that it would cause an increase in the cost of capital are exaggerated. This argument relies on the premise that the ballooning in the high frequency and derivative markets is necessary for asset markets to function. In reality, little harm will be done in purging some of the excess liquidity that these trades have created.

The largest challenge related to the FTT is a policy one. The tax necessarily impacts the most active traders and the largest financial centers, so they could mobilize a lobby in opposition. And if the tax were not implemented on a large scale, trading could move to tax-free jurisdictions. That said, the tax’s potential to fill government coffers will create advocates. Meanwhile, the offshoring of transactions and profits will only accelerate an existing trend – though this too, can, and may be regulated.

In conclusion, it is in the interest of regulators to curb ever-faster trading to restore stability to markets. And it is surprisingly easy to implement since all transactions are captured by electronic systems. A general FTT is consistent with a more pragmatic worldview and has the potential to become the first supranational European tax and finally the first global tax.

Stephan Schulmeister and Alex Hodbod also contributed to this piece.

For more on this subject, visit The Tobin Tax context article.

Note: a previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the 70% anticipated decrease in trading corresponds only to derivatives.

The views expressed in this article are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment