Might 2017 see a repetition of the historical splits in the Conservative Party?

As the many consequences of the June 8 election work through, the United Kingdom is edging closer to a rare historical occurrence already celebrated twice before: a formal split in the (still just about) ruling Conservative Party.

Just as on the two previous divisions, in 1906 and 1846, it seems a split in 2017, inspired by Brexit, may be brought about by irreconcilable differences among Conservatives on free trade.

For centuries, free trade has defined the UK’s mercantilist identity and place in the world. Disputes over it, like disputes over liturgical interpretations at earlier periods of our history, have long defined Conservative politics. In 2017, the party is once again hopelessly split on it. To what degree does the UK’s reasonably successful self-reinvention since the 1980s — replacing lost market share in physical trade by becoming a regional and global entrêpot of innovative, lightly regulated service industries — need cooperation with European Union neighbors? The UK has more limited mercantilist objectives than the often more political aspirations of continental EU members. Is the political price of cooperation worth the candle for the UK? The Remainers among the Conservatives (generally on the left of the party) say “yes.” Leavers (generally on the right) say “no.”

In 1906, the issue was whether the British Empire, like today’s EU, should grant trading preferences to its members (imperial preference) to give a commercial rationale to the treasured empire. But these would usher in higher prices and lower innovation, always part and parcel of protectionism. The Conservative Party’s deep resulting split led to its landslide defeat in the 1906 election.

In 1846, in a simpler world, the topic was the price of bread. Should high grain prices, benefiting the rural economy and rural landlords, be perpetuated in the protectionist Corn Laws, or should the UK food market be opened to lower-cost grain imports to reduce prices for the benefit of rapidly rising urban populations? Here too, the Conservative Party split.

When contemplating the impressive determination of the Conservative Party to remain together, we should not forget that the forces at work in 1846 and 1906 were very similar, and largely on the same issues, to those which exist in 2017. It happened before, and there is no reason for the party not to split again.

Divided and Confused

The June 2017 election, spectacularly not won — but also not lost — by the Conservatives, sought to kick the Brexit can, over which battles have raged within the party ever since the 1970s, once more two more years down the road. Repeated efforts have been made to paper over this party split, without surrendering power, by delegating adjudication to the electorate. These fudges have not only failed in any way to lessen the split in the party, but have now opened up splits in wider British society — between generations, between educated and less educated, between London and the rest of the country — which mirror and amplify those in the party. We have an unhappy, divided and confused country.

Following the 2016 referendum, the newest vehicle for this ever more creative can-kicking by the bitterly divided Conservatives was the concept of a “negotiation” with the EU. The apparently uncertain outcome of this “negotiation” has allowed the party leadership to tell both sides of the Conservatives’ fragile consortium of opponents and supporters of the EU to “wait and see.” In delivering this message to the party’s factions, the enticement of office, made possible by staying in government, has provided much glue.

Transparently, this “negotiation” is very largely a fiction. A bespoke UK deal is, for both sides, too complicated to attempt. Myriad interdependencies have evolved over nearly half a century, which go far beyond trade. They cannot be individually recast, especially not on the fly.

There is no rationale for the 440 million people in the remaining EU, with their $13.8 trillion of GDP, to give advantages, not granted to others, to a local competitor with 64 million people and $2.7 trillion of GDP. Having also so emphatically been told by the UK (and the US) that “us first” is the new mantra for international relations, the 440 million will surely no longer hesitate to make count their much greater economic and political weight. Furthermore, the approval process for a bespoke deal for 27 remaining EU countries would be so technically complex as to be fundamentally unfeasible.

The “negotiation” with the EU will, therefore, be a straightforward invitation to the UK, however politically dressed up, to choose between two existing relationship models.

First, the Norway model: Retain all obligations of EU membership in return for keeping all benefits, but with no formal influence or voice in the EU. Variations of this model are discussed in the UK as “soft Brexit.” Political discussion of why the UK might give up such a large part of its voice and influence in the world, in return for no material change in its EU obligations, has not yet begun, but is inevitable. While better than a “hard Brexit,” a soft Brexit similar to the Norway model would be far worse than the status quo — an extraordinary and historic penalty for the country to pay for the Conservative Party’s activities since 2015.

Second, there is the “hard Brexit”: exit with no deal. After 44 years of partnership in many areas of national life — unlike any other trade partner — this process carries with it enormous risks especially, but not only, for the economy. In the long term even more than the short term.

Back to 1846

Since neither an electoral mandate nor a parliamentary majority exists for either of these alternatives, no UK government, especially not during a hung Parliament, can make this decision without another election.

At this next election, likely at the very latest in 2019, no blame game — “the EU has been unreasonable” — will avoid the necessary decision. The relationship with the EU — hard Brexit, soft Brexit or forget Brexit — will be the overwhelming issue. Instead of, as in the 2016 referendum, comparing Remain with all the other options in aggregate, executable options at this election will need to be compared directly with each other.

At this coming election, the wings of today’s Conservative Party will have to take a clear position and will no longer be able to campaign on the same side. The fudges of 2015 and 2017, in which the party used elaborate fudges to preserve itself and its hold on power, putting its own interests ahead of those of the country, will no longer be available.

We will, surely, be back to 1846 and 1906.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

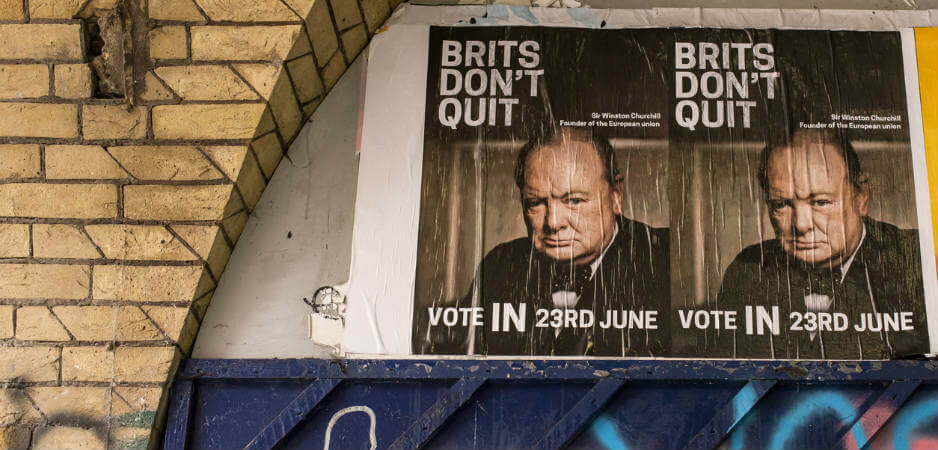

Photo Credit: Nicola Ferrari

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.