Border disputes between India and China are eclipsing a potentially strategic partnership between the two.

If history is any indication, India's failure to recognise the legitimacy of interests other than its own is a besetting flaw in its diplomacy and foreign policy. Reconciliation is the primary object of fine diplomacy and in some cases it may be difficult, if not impossible, to carry out this mandate.

At the root of India and China’s conflicting interests lies a border-dispute, and the process of negotiations between the two nations may be a rather assiduous climb. Since China deployed troops in the region of Daulat Beg Oldi in April this year, India was dragged into a politico-military imbroglio with its mighty neighbour. The dispute reached a crescendo when both countries deployed troops facing each other, ready for action on the ill-defined border. Thereafter, it took several flag meetings, in addition to an intense diplomatic flurry on either side to dial down the stress.

Yet, the abatement of tensions near the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Ladakh came not a day too soon. In contrast, with its "idealism" and "romanticism" under Nehru that were dented by China’s consequent "betrayal" in the 1962 war between the two neighbours, the Indian government has acted more reasonably this time round. Remarkably, there was no exchange of fire between India and China even though their troops were on the brink of engagement. On the contrary, India has played a proactive role in seeking a diplomatic solution to the problem, which thankfully remains concilable.

Undefined Border

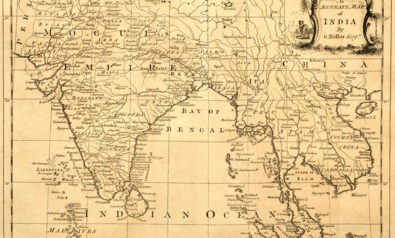

In 1950, the Survey of India issued the first map of India as an independent country. In this map, the political divisions of the new republic were well-defined with Pakistan, both in the west and the east. They were also fairly clear with China, except in three areas where they were marked as “undefined". First, in the extreme east, the Tirap subdivision, which is present-day Arunachal Pradesh; second, the central region of what is today Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh; and third, the eastern Kashmir including Aksai Chin. However, in 1954, the Survey issued a new set of maps wherein the “undefined” colour wash was replaced by a hard-line depicting Aksai Chin as part of the Indian territory. Not only were the old maps withdrawn from the Survey archives, but drawing the Indian map in the old way was made illegal as well. Nehru’s speech to the Indian Parliament in 1950, after the first set of maps was published, is particularly significant in this matter:

“To admit that a lingering doubt remained in my mind and in my minister’s mind (K.M. Panikkar) as to what might happen in the future. But we did not see how we were going to decide this question by hurling it in that form at the Chinese at the moment. We felt that we should hold by our position and that the lapse of time and events will confirm it and by that time perhaps, when the challenge to it came, we would be in a much stronger position to face it. I may be perfectly frank to the House. It is not as if it was ignored or that it was not thought about.”

This speaks volumes about what Nehru’s intention was behind the unilateral act of changing the border at Aksai Chin. China was obviously not amused. When the devious act came to light, Nehru defended the new border repeatedly arguing that the McMahon Line was a treaty line, and historical evidence showed that the territories claimed in 1954 were always associated with India since ancient times. In the midst of this debacle, the then Chinese prime minister, Zhou Enlai, issued the following reply in 1959:

“First of all, I wish to point out that the Sino-Indian boundary has never been formally delimitated. Historically no treaty or agreement on the Sino-Indian boundary has ever been concluded between the Chinese Central Government and the Indian Government. So far as the actual situation is concerned, there are certain differences between the two sides over the border question… The latest case concerns an area in the southern part of China’s Sinkiang Uighur Autonomous region, which has always been under Chinese jurisdiction. Patrol duties have continually been carried out in the area by the border guards of the Chinese government. And the Sinkiang-Tibet Highway, built by our country in 1956, runs through that area. Yet recently the Indian government claimed that the area was in Indian territory. All this shows that border disputes do exist between China and India.”

The dispute became a thorn in the diplomatic ties between India and China, mainly due to the fact that the two neigbours never really sat down to discuss the issue. China’s case in 1962 centred on India’s unilateral action allowing them to justify their incursion. (This is, however, somewhat ironic when it comes to Beijing’s own claim on Tibet, especially when the communist regime has never been able to come up with a good case to justify it.) The Chinese empire was never clear about its western extremities. Further, it rejected any British attempt to demarcate the border and settle the issue once and for all.

Aksai Chin is a high-altitude uninhabited desert and of little strategic importance to India, but it is vital for China. Geographically, it becomes imperative for China to control the western border of Tibet in view of its strong claim over the disputed land. As a result, China entered the Indian territory and exploited the issue of an undefined border to its advantage. It developed the Aksai Chin road, which cut through the McMahon Line into Indian territory. Instead of negotiating the issue with its neighbour when it discovered Beijing’s advances into the territory in 1961, New Delhi plunged straight into a war only to suffer a crushing defeat at the hands of the communist regime. The indignation went deeper as India ended up losing even more ground to China.

Overlapping Claims

Historically, transgressions have been made on either side. But it’s high time the two emerging world powers settled their thorny territorial disputes for their own good. At present, China’s incursion into Daulat Beg Oldi cannot be considered in isolation as it appears to be part of a larger strategic plan to strengthen its control over Tibet; hence, strengthening apprehensions over whether China will settle on anything at all. Until now, the LAC is only a notional line that has never been marked or accepted in mutually agreed maps, let alone defined in a document with specific geographical features. Nevertheless, it has been reasonably adhered to by both sides. In some parts of the LAC, however, either side has overlapping claims leading to conflicting border patrolling routines. In the past, China has on some occasions withdrawn from particular areas after an interval of time.

Even though China may seem to be dragging its feet on the border issue, there is hope that a lasting solution can be achieved under the new Chinese leadership. In a strong sign of Beijing’s willingness to warm up to its southern neighbour, Chinese President Xi Jingping described India as its "most important bilateral partner" at the Durban BRIC summit earlier this year. He further added that the working mechanism on border management between the two countries should strive for “a fair, rational solution framework acceptable to both sides as soon as possible”.

Way Forward

India and China are major trade partners, and each is monetarily invaluable to the other. Border transgressions and lingering territorial disputes stand to undermine a potentially strong strategic partnership between the two emerging economies. Despite China’s unquestionable militrary superiority, any showdown will inarguably hurt both neighbours and foster regional imbalance. With respect to the existing border disputes between the two, it is important to note that China has staked claims after developing the areas of Aksai Chin and Tirap, whereas India has shown no such interest in the regions.

New Delhi, in particular, needs to focus on other much more serious border issues it has with Pakistan. Its failure to resolve the dispute over Kashmir with Pakistan is far more damaging for India at national, regional and diplomatic level. India’s porous borders with both Pakistan and Bangladesh have been repeatedly exploited by terrorist outfits, and therfore, have cost it gravely. New Delhi has too much on its plate; It's time India shut the book on its border disputes with Beijing for good.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment

Also, since the author seems to be interested in research, a little effort would show the duplicity of the Chinese who have used every single occasion of bilateral dialogue between India and China to flex their muscles, except may be the visit of Rajiv Gandhi in the eighties, which in any case a visit by a top Indian leader was taking place for the first time after the ’62 war, so they probably did not want to rock the boat. Otherwise every single occasion of bilateral meetings between India and China has been used by the Chinese to flex their muscle, and to show India who the boss in the region is. Is that behaviour consistent with good neighbourly intentions? If the author really has to write such an article, she should address the Chinese, telling them that it is not in their interest to pursue this duplicitous policy towards India. Otherwise, all the major Chinese cities are under the aim of nuclear tipped Indian missiles. And this is not jingoism, but plain realism. Since the author is an Indian, I would advise her to stop being so obsequious towards the Chinese.

This is a laughable travesty of a scholarly article, where frankly the author does not know what position to take, except to browbeat India. “India’s failure to recognise the legitimacy of interests other than its own” – seriously? Since the author is more interested in calling India names, probably the acceptance and public declaration of Tibet being part of China according to the author would be capitulation, and would not fall in the category of recognising China’s interests. If India in its own interest decided to persist with the McMohon line, which China does not recognise, how does that mean that India does not recognise China’s interest, or does not have the propensity to do so? On the other hand, in fact, the author’s phrase, “failure to recognise the legitimacy of interests other than its own” is actually more apt for China. We just have to see the history of border disputes that China has with practically all its neighbours, and those that are settled are ones where China has pretty much arm twisted the neighbour to accept the solution which was acceptable to China, and not mutually acceptable in reality. So who consistently fails to “to recognise the legitimacy of interests other than its own”. It is China, and not India. The fact of the matter is, the Han Chinese are still smarting, after several generations for all the humiliations they suffered at the hands of the West, and it is not acceptable to them that the Middle Kingdom suffered thus. To accept it as a historical fact and move on is something that the Han Chinese, suffering from a nationalist egotism, will never accept. So they, led by the CCP and PLA which are jingoism and revanchism concentrated several times over, will keep working towards the reality of actuating the Middle Kingdom once again. All this trade etc. is just aimed towards creation of that hegemony, never mind if millions of artisans and workers in the third world whose cause the Chinese claim to champion, are losing their livelihoods.

As far as India is concerned, in the present NDA government, we have for the first time a dispensation that is standing up to the bullying of the Chinese.

I also see the author trying in vain to hyphenate India and Pakistan. The fact of the matter is, Pakistan is loose change as far as India is concerned, it is the increasingly aggressive Chinese that we have to work at.

Really wonder what the interest of this author is – is it just the love of the Chinese, or something else, in writing this article.