Will the US help its Southeast Asian allies in the case of a serious military conflict with China over the South China Sea? With America's pivot towards Asia, are we expecting a new 'American Century'?

During the first decade of the 21st century, international headlines were fixated on the growing clout of China in Southeast Asia. Since the beginning of this decade, however, China’s ‘charm offensive’ has been eclipsed by the story of America’s return to Asia. Widespread fear of Beijing’s uncertain strategic posturing has played a key role in this dramatic transition. Equally significant is the expedient convergence of some illusions on the part of certain Southeast Asian countries and of the US. Recent events in the South China Sea provide a perfect example of mutually expedient illusions together shaping geopolitical realities.

‘Middle Power Dreaming’

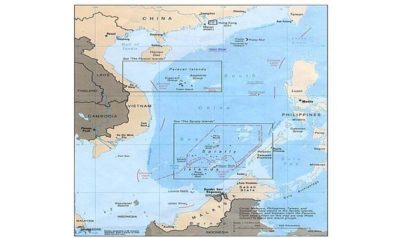

In the long-running South China Sea disputes, some regional claimants have become increasingly assertive. Both Vietnam and the Philippines, for example, have been actively working with international oil companies like ExxonMobil and Chevron in the disputed areas. After the alleged Chinese sabotage of Vietnamese oil exploration vessels in May 2011, Vietnam responded with nine hours of live-fire naval exercises off its central coast. On the same day, Hanoi issued an order about eligibility for military conscription, an unusual move apparently designed to warn China that Vietnam was prepared to up the ante in the dispute. At the same time, the Philippines took the dramatic step of officially renaming the South China Sea the ‘West Philippine Sea’.

The precise reasons behind these countries’ more decisive actions are not known. Many believe that they were responses to China’s increasingly assertive diplomacy. But to categorize all these recent measures as mere responses would be to underestimate these countries’ strategic initiatives. A more plausible explanation is that their actions have been to some extent buoyed by the renewed American focus on the region.

Indeed, one month after Vietnam’s live-fire artillery training in June 2011, Hanoi held joint naval exercises with the US Navy. In April this year, the US and the Philippines staged their annual war games in a mock assault to retake the island of Palawan, amidst a two-month-long standoff involving Chinese and Philippine vessels at Scarborough Shoal. These shows of force would be uncharacteristic of the diplomatic style of these middle powers whose economy depends heavily on trading with China, were it not for their hope that the US could now lend a helping hand.

But such expectations raise the question of whether the hope for American intervention is realistic. It is obvious that the US, wary of Beijing, is determined not to allow China to dominate the region at America’s expense. The US has therefore taken advantage of the rising tensions in the South China Sea to facilitate its pivot to Asia.

It is less clear whether the US would be willing to fight China alongside its Southeast Asian ‘allies’ should disputes in the South China Sea escalate. Some countries, taking their cue from strengthening military ties with the US, may assume that Washington will come to their aid. Yet, despite the US desire to contain or constrain China, China is still critical in tackling a number of other pressing global challenges, such as nuclear issues in North Korea and Iran.

Thus, Vietnam, the Philippines and other countries in the region need to recognize the increased US interest in the South China Sea for what it is: an expedient opportunity for strategic rebalancing in the region. Along the way, Vietnam and the Philippines may well get some useful leverage over China, but to count on the US to join them in any serious conflict with Beijing would be, to borrow a book title, ‘Middle Power Dreaming’.

Even if the US were a dependable ally and were prepared to confront China on behalf of its Southeast Asian allies, a US-China conflict could hardly deliver any real benefits for the middle powers in the disputes. As the saying goes, when two elephants fight, the grass will suffer. Perhaps realizing that there is a limit to the strategy of playing China and the US against each other, the defense chief of the Philippines recently reached an agreement with his Chinese counterpart about the need for restraint in their disputes.

A New ‘American Century’? Another American Dream.

Washington’s pivot to Asia, timed with the region’s growing unease over China, has been a brilliant strategic move from the American perspective. Walter Russell Mead declared that “the US has reasserted its primacy in a convincing way”. Within a year or two, regional powers seem to have turned their back on China’s ‘charm offensive’ to re-embrace the US.

On this occasion of ‘smart power’ competition between the US and China, the former has clearly won the first round. According to some US policy-makers and strategists, there is more to come. According to Obama, “In the Asia-Pacific in the 21st century, the United States of America is all in.”

Hillary Clinton proclaimed in a Foreign Policy article that we are witnessing the beginning of another American Century, a ‘Pacific Century’ eagerly anticipated and welcomed by key allies and friends in the region. If such statements are not mere political rhetoric anticipating the Presidential elections later this year, then it must be said that there appears to be more than a whiff of strategic illusion, American style.

While the ‘Manifest Destiny’ mantra proves to be irresistibly attractive among a significant section of American society, most signs suggest that the ‘American Century’ is over. This is not to agree with declinist theory, nor is it to suggest that a Chinese or Asian Century will take its place. Rather, the whole notion that one century ‘belongs’ to a single country or a single continent no longer makes much sense, if it ever did.

In this context, the warm reception of America’s return to Asia says more about some Asian countries’ anxiety regarding China than about their ringing endorsement of American primacy per se. Most people in Asia are pragmatic. While they may wish to hedge their bets between the US and China, they have shown little appetite for ideological grandstanding or narcissistic delusion.

In the middle of the last decade, George W. Bush mistakenly believed that all countries were on board with his ‘War on Terror,’ and so, wherever he went, he talked verbosely about terror and not much else. But Karim Raslan, a Malaysian writer, commented that “We’ve all got to live. We’ve all got to make money.” And to make money, most politicians in the region understand that they have to engage with China. Now boasting the second largest economy in the world, China is not the Soviet Union of the Cold War. It is either the largest or the second largest trading partner to most of its neighbors. While those countries understandably want to hedge against Beijing’s future ambition, none of them is willing to sacrifice vital trade ties with China to boost the stock of another American century.

The most likely exceptions are Australia and Japan, but even these countries are nervous about the prospect of a US-China conflict. As an Australian official put it, “We will go up a hill with you [the US], but not march over the cliff”.

Time for a Reality Check

In international relations, illusions are not merely harmless fantasies. When political actors act upon them as ‘truth’, they are capable of constituting reality. The current situation in the South China Sea has been shaped in no small part by the aforementioned illusions. But the unfolding crisis is hardly in any country’s long-term interest, except for serving brief political or nationalist goals. It is therefore time for all countries concerned to have a reality check and pull back from the brinks of these illusions. Otherwise, it is not inconceivable that the players in the region might continue to be bogged down in ever-spiralling disputes and competition that do not bode well for US-China relations or regional stability.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment