Banning books in India is a delicate game of community politics.

When it comes to banning books, India is a front-runner in the democratic world. Add to it the long list of films, plays and exhibitions, which could not be produced or shown due to protests from some group, the restrictions placed on freedom of speech and expression in independent India appear even more daunting.

Indeed, toward the end of the 20th century, India was following a trajectory that was not being pursued in most liberal democracies. But this seems to be changing now as more and more countries in the Western hemisphere are walking down the same lane. While they are still reluctant to ban books and criminalize insulting speech, in many other respects they are catching up with India rather swiftly.

Unconditional Right: Freedom of Speech

Freedom of speech and expression is never an absolute and unconditional right. Everywhere it is subject to some restrictions. In the second half of the 20th century, most Western democracies accepted John Stuart Mill’s wisdom that individual liberty was of the utmost value. Freedom of speech and expression was an embodiment of that liberty and it should only be curtailed when it poses a real and imminent danger to the life and liberty of another person.

This expanded the space for free expression. As a consequence, countries which frequently banned books in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for encouraging violence or crime, corrupting the young, using inappropriate language and social obscenity — books like Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H Lawrence, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, As I lay Dying by William Faulkner — made space for individuals to voice their views, so long as they did not directly cause harm or physical injury to another.

India has, however, continued to move against this liberal current. Unlike Europe and America, successive governments at the center as well as state (regional) governments have followed a policy of banning books. Authors have been, and continue to be, ostracized and left to defend themselves against organized group of protesters, with virtually no support from the state machinery.

Looking at the frequency with which bans have been handed out, it is easy to conclude that India is out of step with the rest of the liberal world. Unlike Europe and America, it has failed to protect individual liberty and, with it, freedom of speech and expression.

At times, relief has come for authors and producers from the Supreme Court. In cases that reached it, the Court scrutinized the grounds for restriction and, on occasions, overturned the bans. But these are just a few cases and judgments have come at the end of a long drawn out process.

Community Concerns

Perhaps the most puzzling and somewhat disturbing element is that demands for banning books or prohibiting certain kinds of expression have not gone down with the passage of time. If anything, such demands have become more frequent and shrill as the political system has democratized to accommodate regional and group differences.

In most instances, one confronts a familiar pattern of events. A small, rather localized, group protests against a book or film claiming it has hurt community sentiment or misrepresented the history and tradition of their community. In a short interval, political parties in the region jump in to support these claims in the hope of winning the sympathy and support of the community, whose sentiments are supposedly hurt. Governments in office pursue the same logic and act so as to appear sensitive to the cultural concerns and beliefs of that community.

Today, there are only a few books and films that are banned all across India. What is more common is the banning and prohibition on the sale/viewing of a book/film by one or more state governments. So the disputed text is not available in specific parts of India but, given the federal structure of the polity, it is available in other parts of the country. To take an example, the film The Da Vinci Code was banned in seven states but could be viewed in the remaining 16 states and union territories. Besides, the film was banned but the book was available everywhere.

At the end of the day, whether the text is available or not to readers/viewers becomes a secondary matter. What remains significant is the posturing by different political groups and the show of being attentive to community concerns.

Cultural Nationalism

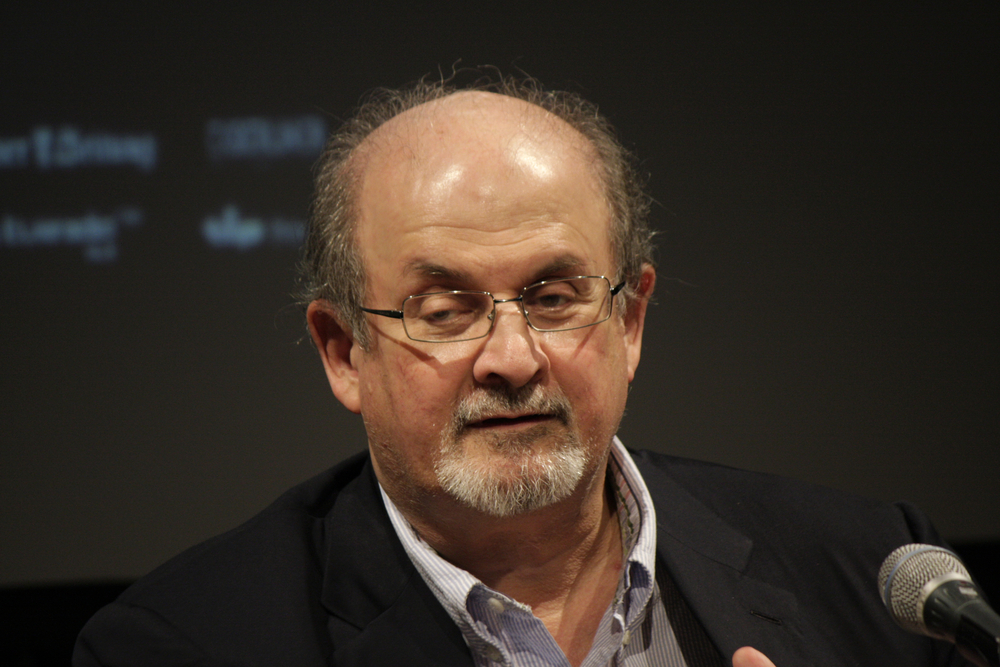

It is this dimension of the politics of banning, which suggests these actions are an integral part of identity politics that structures electoral democracy in India. So strong is the urge to win the support of the community that governments sometimes take preemptive measures and ban an expression, even before protests against it surface. This is what had happened in the case of Satanic Verses.

With Salman Rushdie’s controversial novel, the government acted to protect the perceived cultural interests of the minority community. But this is not always the case. In a large number of cases, sections of the majority community have demanded, and obtained, a ban on the grounds that the published work misrepresents its history or tradition. Indeed, incidents of the latter kind have been on the increase since the 1980s and have been an integral part of the agenda of cultural nationalism.

It is not just political parties, of all hues, that are succumbing to pressure but also public bodies, such as universities as well as publishers, that have all too frequently caved under pressure that came from social and political organizations, and even fringe groups. The decision by Oxford University Press, in 2008, to stop the publication of the volumes that contained A.K. Ramanujan’s essay, Three Hundred Ramayanas and, more recently, Penguin Books’ decision to pulp Wendy Doniger’s book — The Hindus: An Alternative History — as a way of settling the ongoing legal suit, are just a few examples of this.

This picture would not be complete without mentioning that those who speak for, and in the name of, a community do not go unchallenged. Civil society collectives often come together to counter the protesters, so there is a contest in the public domain and this gives the challenged text a new audience. Bans are not, therefore, successful in completely eliminating access to the text. While they place certain hardships on those who wish to read or access these texts, what is more troubling is the immense cost they place on the individual author or producer.

Politics of Bans

There is thus an underlying politics of bans and this cannot be ignored if we are to understand India. However, politics constitutes the implicit context in which bans operate, and not their justification. Most of the time, political organizations and governments defend their decision to ban on the ground that the identified text (or sections of it) is offensive to members of a given community; or that it is likely to incite communal hatred.

In case of the latter, the anticipated harm or threat to law and order is at best expected and rarely ever imminent or immediate. On a few occasions, books have been banned for misrepresenting India and her foreign policy in such matters as the Sino-Indian War or policy toward Sikkim. Whether it is the nation (political community) or the ascribed community that is prime consideration, either way bans have created an environment in which the community has been foregrounded and its claims allowed to trump individual liberty.

Looking at the frequency with which bans have been handed out, it is easy to conclude that India is out of step with the rest of the liberal world. Unlike Europe and America, it has failed to protect individual liberty and, with it, freedom of speech and expression.

But the contrast that was so marked toward the end of the 20th century appears less stark today, as more and more democracies are moving away from Mill’s harm principle and restricting freedom of speech and expression on account of it being offensive to a community or group. The number of individuals being prosecuted for speech that is considered insulting or distressing to a group or community, indecent, obscene or likely to incite religious hatred are continuously rising, and some estimates suggest that more than a thousand cases are registered every year on these grounds. Charges filed against Michel Houellebecq, Brigitte Bardot, Geert Wilders, Pamella Geller and Robert Spencer are just a few notable examples of this. There are, of course, many more cases of this kind that do not make the headlines.

The point is that more and more democracies are today acting on the belief that respect to the individual requires respecting their beliefs, or at least respecting that which they regard to be sacred. Governments are beginning to accept that attempts to ridicule and humiliate a person, particularly members of a minority, can cause a sense of anxiety and alienation, and this can be an obstacle to creating an integrated society. As such, they are being more and more attentive to the protests and demands that come from vulnerable minorities in their society. It is against this background that we need to ask just what should be the acceptable limits to free speech.

At present we have an impasse with strident defenders of all forms of free speech and expression, on the one side, and those seeking restriction on offensive speech, on the other. The reality is that the issue of free speech and hate speech is too complex to be resolved in either/or terms.

There is a need for a more sustained debate on this subject. But we can start it off with the observation that in plural democratic societies, freedom of speech and expression can only be protected when individuals cultivate a judgment — a capacity to differentiate between critique and ridicule/insult — so that individuals and groups can, by and large, draw a boundary line for themselves. Failure to do so is likely to see greater governmental interventions and restrictions on freedom of speech and expression.

Equally, one needs to remember that we are unlikely to agree with every member of our society and everyone else is unlikely to agree with us on all matters. Hence, there are bound to be views that we find unacceptable or misrepresentations of who we are. There is no doubt that systematic targeting of an “other” can have an adverse effect upon them — nevertheless negative representation by a miniscule minority can be ignored. They gain the capacity to “harm” when they become the voice of the majority or the expressions of the state, which has an authoritative presence.

There needs to be a focus on official misrepresentations rather than the one-off case, as that is likely to be the strongest protection for the self as well as for the freedom of speech and expression. The state on its part has an obligation to be critical of its own cultural narrative and representations of “the other,” for that structures the conditions that enable individuals to lead a good life. When the latter are in place, individual detractors can be ignored and easily forgotten.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment