Given Singapore’s position as an international financial centre, the macroeconomic impact of the global financial crisis on its economy has been significant. What steps can be taken to help it recover?

Like many open economies worldwide, the recent global financial crisis which started in the US triggered a marked slowdown in Singapore’s economic growth.

As an economy structurally dependent on international trade, Singapore’s export sectors were affected by a slump in export demand. At the 10th Singapore Economic Roundtable, it was observed that the most iconic industries of Singapore's value-adding restructuring effort – bio-medicals and tourism – relied heavily on external demand and had ironically made Singapore more vulnerable to the recession. Singapore was also one of the most exposed Asian economies during the crisis; as although volumes of intra-Asian trade in intermediate goods increased, G3 markets remained the final export destinations of high-end manufacturing products such as electronics. In 2008, GDP contracted due to manufacturing in Q2 and then the slippage extended to construction and a broad range of services.

Singapore’s position as a trade hub supporting trade-related services from transportation to trade finance meant that the slowdown had ramifications exceeding the export-oriented manufacturing sector. Its financial services industry contracted and trading activities fell substantially in foreign exchange, stock brokerage, and fund management. This accounts for why Singapore was one of the hardest hit economies during the global downturn. In fact, this financial crisis was the worst Singapore experienced since its independence in 1965. The downward pull of the global recession on Singapore’s economy continued into 2009 as negative GDP growth was forecasted at -9% to -6% (see Chart 1).

Impact of the Financial Shock on Singapore

At the initial onset of the global crisis in Q3 of 2007,minimal exposure to toxic assets meant that financial headwinds from the US and Europe were manageable. While banks in Singapore did have some exposure to collateral debt obligations, their assets were relatively safe and much less leveraged than banks in the United States and Europe. However, the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in mid-September 2008 registered spill-overs which were significantly more severe. As the risk appetite dramatically receded, financial transactions froze globally and Asia-Pacific financial markets faced sharp deterioration from mid-to-late 2008 due to falling confidence, bleak global outlook and fears about short-term funding availability.

The impact of the financial shock on Singapore's economy and GDP can be analysed through several key channels as laid out by economists at the 10th Singapore Economic Roundtable, which was organised by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) of Singapore. There was firstly an immediate impact on sentiment-sensitive segments of the domestic financial sector, evident in the high degrees of volatility in the local stock market, the Straits Times Index (STI). Stock market volumes and prices fell considerably from their peak in July-October 2007. As falling asset prices led to declining household wealth, consumer spending contracted which affected property sales and financial intermediation activities. Secondly, there was an effect on investment spending. Prior to the sub-prime crisis the cost of corporate financing was at a historic low. The credit crisis led to increasing scarcity and higher financing costs. This affected investment spending as projects were postponed or cancelled if their returns could not justify the cost of funds.

In addition, international banks and institutional borrowers faced the stress of a credit crunch. With the exception of Hong Kong, Singapore’s financial sector experienced the greatest decline in cross-border loans as a percentage of GDP, which were very high prior to the crisis and shrank when risk appetite receded. In the two years prior to the global financial crisis, the gross value of financial account transactions increased by a factor of more than three in Singapore, mostly due to increases in portfolio investment. In spite of this heightened potential vulnerability to capital reversals in the region, Singapore’s vulnerability to a slowdown in the financial market and capital outflows was buffered by a consistent current account surplus, and a high sovereign rating of AAA.

Targeted Recovery Policies

In the aftermath of Lehman Brothers’ collapse and panic across financial markets abroad, it was essential to ensure the stability of Singapore’s financial system and boost market confidence. Singapore’s central bank, The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), reacted by keeping a higher level of liquidity in the banking system and was ready to inject additional liquidity to ensure that the interbank market did not come to a standstill as a result of tightening credit conditions. MAS also established a precautionary swap facility of up to US $30 billion with the Federal Reserve Bank in the United States to ensure that local financial institutions maintained access to US dollar liquidity.

In addition, the Singapore government sought to mitigate the bleak global outlook by issuing a blanket guarantee in October 2008 on all Singapore Dollar and foreign currency deposits at banks, finance companies and merchant banks, effective until the end of 2010. This guarantee, extended around the time that other countries in Asia were also doing so, helped to support the stability of the Singapore economy, but had to be backed by more than S$200 billion of national reserves. The Singapore government had offered a range of liquidity and credit support lines to smaller businesses and support for low income households. Thus, even though the GDP plunged, the welfare impact was actually quite minimal.

Singapore also enjoyed budget surpluses in the years preceding the crisis which enabled it to draw on S$4.9 billion of fiscal reserves to spend on a significantly expansionary budget for 2009, in order to sustain a fiscal stimulus package. The government budget for 2009 was brought forward by a month to January, even as resilience measures had already been implemented in late 2008 to help struggling local firms. The 2009 budget’s “Resilience Package”, aiming at helping businesses to retain workers, amounted to S$ 20.5 billion. S$5.1 billion of this was spent on helping to preserve jobs, and S$5.8 billion extended to stimulate bank lending through a Special Risk-Sharing Initiative (SRI).

Emerging from the crisis

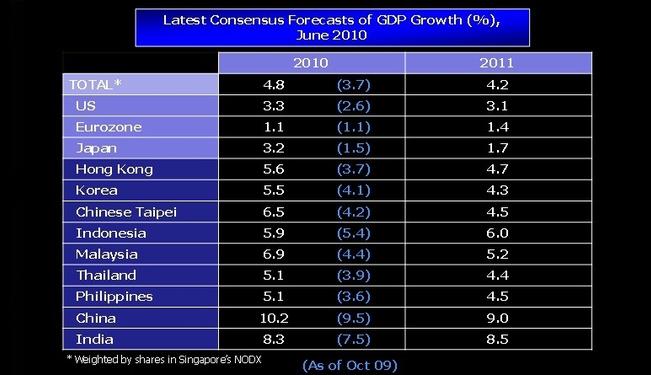

The worst of the global financial crisis appears to be over. Global financial conditions have improved strikingly and the prospects for the world economy have perked up. Asia, excluding Japan, is leading the recovery, with its GDP already surpassing the pre-crisis level. For the whole of 2010, Asia, led by China, India, and other Newly Industrialised Economies (NIEs), is expected to grow over the previous year (see Chart 2). The Singapore economy, too, has rebounded significantly and is expected to grow by 13 – 15% in 2010, with manufacturing and services spearheading the recovery (see Chart 3).

While the immediate outlook is encouraging, Singapore will remain alert because the structural headwinds to growth in advanced economies remain. The transition from government-led stimulus to sustained private-sector driven growth may be more challenging in those economies which face rising sovereign debt levels. As global liquidity conditions normalize, following the unprecedented easing of interest rates by major central banks, financial markets could experience bouts of volatility as a range of asset classes are re-priced and this could impact negatively on various interest-sensitive industries.

Reforms of the global financial system have to be carefully thought through, regulated and sequenced. It is important that reforms do not become politicised, with a rush to adopt simple rules that seem to solve the problems. Specific measures, each of which is sensible, may collectively create unintended outcomes and block the promising economic recovery.

Learning Points and Conclusion

Most discussions thus far have been framed around the premise of how to prevent a similar crisis from happening again. . While there is a clear need to look back and learn from the crisis, it is also important to look forward. We must not only fight the last war. In the years ahead, significant restructuring of the global economy is necessary. Hence, there are grounds to believe that a more primary question to frame the discussion is: "How do we make the global financial system more resilient and at the same time support economic restructuring and sustainable global growth, given the economic changes and challenges ahead?"

Even as Singapore recognizes the need to continue development of its financial markets, considerable risks and policy challenges still remain for the region. As far as Singapore is concerned, the city-state will continue with its three pillar approach of sensible rule making, effective supervision, and partnership to achieve the desired outcome.

Asia should take advantage of the global reform agenda to strengthen its regulatory and supervisory regimes, consistent with international standards and best practices, but in a manner that is sensitive to the regional environment and needs. With Singapore being confident in the partnership of financial supervisors and the industry, the resilience of the global financial and economic systems can be strengthened going forward.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment