With Modi in office, the political class and electorate need to reflect on challenges that India faces.

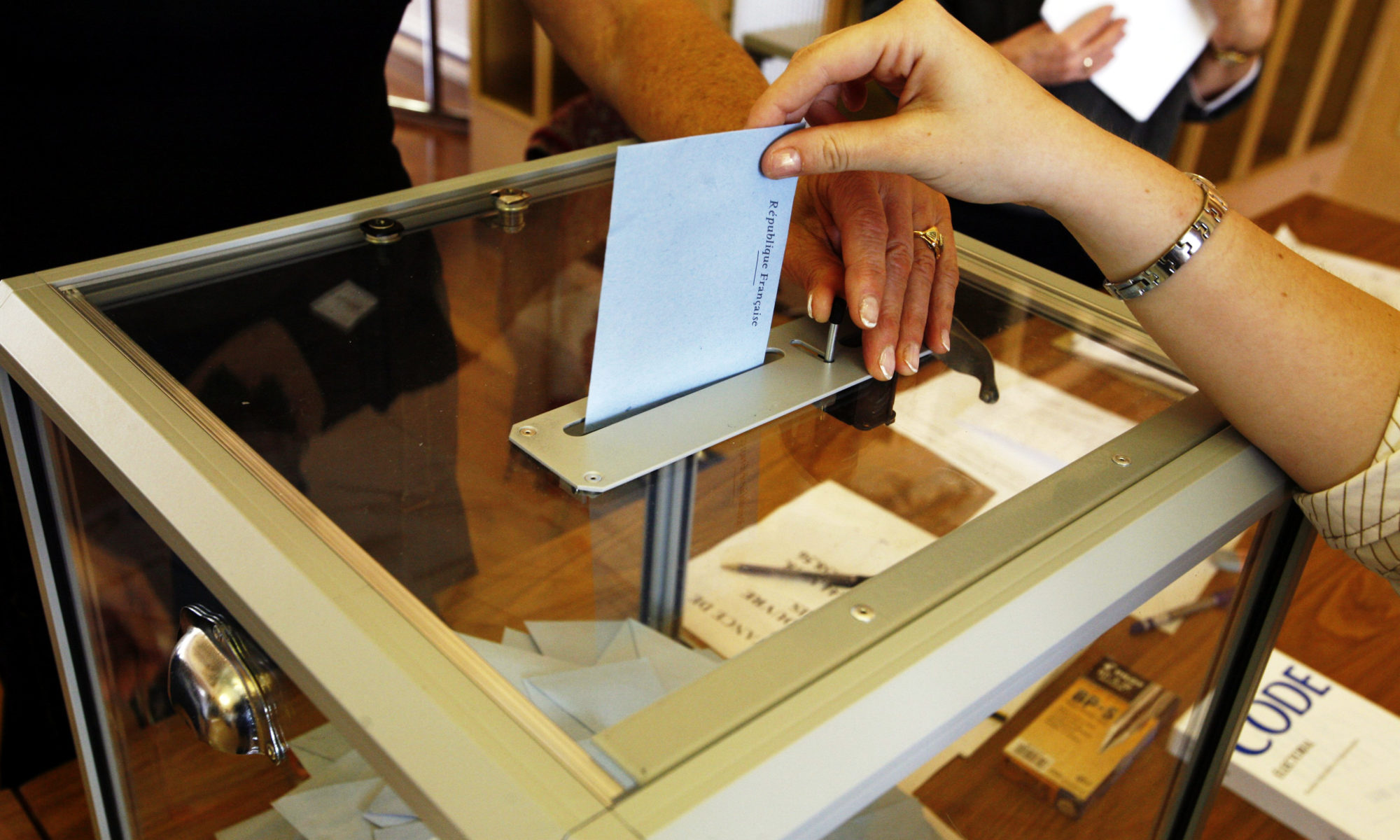

The Indian general elections for the Lok Sabha (lower house of parliament) concluded with the declaration of results on May 16. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) defeated the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) with an absolute majority, a feat that has not been achieved since 1984. Amid the challenges that await the new government, certain questions arise: What drove the 2014 Indian general elections? Why did the people vote?

For Indians, the elections were about change, which, some would argue, is usually the case. What is significant here is the UPA’s second term in office, since 2009, had been marred with corruption, scandals, inflation and a general policy paralysis. It left the Indian populace disillusioned with the ruling coalition. Interactions with voters on polling day revealed that many of them voted just to ensure that Congress did not return to power. As a cab driver from Bombay told this author: “There is no doubt that the people will vote the Congress out of power this time. The situation has only gone from bad to worse under their rule.”

The UPA’s Decade

The UPA’s first term in office between 2004 and 2009 was a success. In 2005-06, the government passed the Right to Information Act and the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. The growth of India’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2005-06 and 2007-08 was over 9%. When the global financial crisis struck in 2008, India’s GDP came down to 6.7%. It should be noted that despite this slump, the country’s GDP was still beyond what the National Democratic Alliance could achieve in its tenure: 5.9%.

However, where did the UPA go wrong between 2009 and 2014? The standard argument was about fluctuations in the global economy, which were beyond the government’s control. In fact, the UPA was caught in a policy paralysis. Essential reforms in infrastructure and taxation were stalled.

The Indian government went back and forth on foreign direct investment (FDI) in the retail sector, which serves as a key example of policy paralysis. In November 2011, the UPA had approved foreign brands to own 51% in multi-brand retail stores. However, in December 2011, the government put FDI reforms on hold, primarily due to opposition from within the ruling coalition. Opponents to FDI claimed that foreign retailers would hurt domestic businesses. The UPA shelved reforms till a consensus was reached with these opponents. In January 2012, the government introduced FDI in single-brand retail.

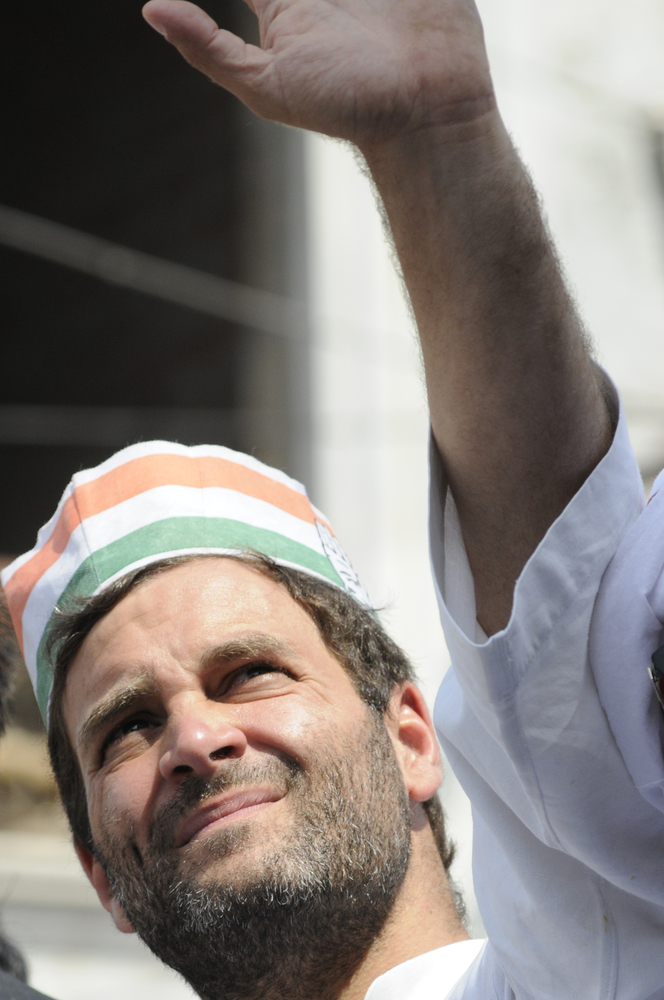

Modi portrayed himself as a leader of development and someone who can jumpstart a stagnant economy, while Rahul Gandhi remained largely inaccessible throughout the UPA’s ten years in power. When the latter addressed voters, what he said made little sense. It is clear why Indians chose not to back him.

Then-Prime Minister Manmohan Singh did not push enough for FDI reforms. Coalition politics was the cited reason behind this. Over the last few years, regional parties, with their own needs and aspirations, have played a crucial role in Indian politics. “The difficult decisions we have to make are made even more difficult because we are a coalition government. We have to formulate policy with the need to maintain consensus,” Singh told parliament in March 2012.

It is difficult to introduce and pass legislations in a coalition. The leader of a coalition is bound to face opposition at every step of the way. In the UPA’s context, led by Congress, the issue was an absence of a clear chain of command. The UPA and Congress top brass comprised Prime Minister Singh, UPA Chairperson Sonia Gandhi and Congress Vice President Rahul Gandhi. Yet the functioning was rather curious. Political decisions were made by Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi, while administrative and policy decisions were left to Singh. On the face of it, this arrangement was perfectly acceptable and workable. In the age of coalitions, political and administrative decisions are bound to overlap, as was seen in the context of FDI reforms. However, the multiple centers of power within the coalition again resulted in policy paralysis.

The UPA’s leadership arrangement worked during its first five years. The cracks began to appear in its second term. The UPA, especially the Congress party, lost credibility among the public. A series of scams came to light and overwhelmed the UPA. Paradoxically, in 2010, Sonia Gandhi made fighting corruption the mainstay in the Congress party’s 83rd plenary session.

Nevertheless, the UPA’s sincerity about dealing with corruption is debatable. The parliament passed the Jan Lokpal bill in December 2013, which provides for the creation of a strong ombudsman to deal with corruption in public offices. However, Congress suffered heavy losses in Assembly elections across four states before the bill was passed. Public anger toward corruption resulted in Congress’ defeats. The passage of the bill was a ploy to pacify the people before parliamentary elections. Though the bill was well-received, it did little to restore Congress’ tainted image.

The Main Faces of the Indian General Elections

Meanwhile, two important faces dominated the general elections of 2014: Narendra Modi of the BJP and Rahul Gandhi of Congress. Until last year, Gandhi was to be the UPA’s prime ministerial candidate. Even, Singh had said on record that he would not mind working under him. However, earlier this year, Congress decided against naming Gandhi as the prime ministerial candidate for the party. This change was a face-saving tactic by Congress to spare him from any blushes caused by the UPA’s defeat.

So, where was Gandhi in this equation? According to Bloomberg View, voters in India were no longer impressed by pedigreed politicians like Congress’ vice president. He was largely inaccessible to the public since the party came to power. As a leading national daily said: “In the Congress, the leader resides somewhere higher up, in an invisible, semi-ecclesiastical order. He is hardly seen and rarely heard. Invisibility imparts a divine aura just as acquired stoicism can so easily be mistaken for wisdom.”

Gandhi’s invisibility annoyed voters. For instance, after the gang rape of a 23-year-old woman in New Delhi, Indians were out on the streets protesting against the heinous act. This presented an opportune moment for Gandhi to address New Delhi and India. While he met a few protesters at his residence, Gandhi did nothing beyond this low-profile meeting. Later, as it turned out, he was abroad and his location was not disclosed, for security reasons. Gandhi often portrayed himself to be a youth leader. Protests after the rape were led by youngsters. Yet his absence at the time — irrespective of whether he went abroad — communicated more than he could have ever done in person.

The Indian electorate clearly believes Modi is the man to lead India. This was shown by the overwhelming mandate the BJP received. A cursory glance at the BJP election manifesto suggests the party, under Modi, will focus on rejuvenating the economy. The “Reform the System” chapter in the manifesto promises good governance, which will be transparent, effective, involving and encouraging, and include administrative, judicial, police and electoral reforms.

Modi claimed repeatedly that he is the champion of development. He had the backing of most business houses, big or small, across India. As one survey concluded: “After a long policy drought, CEOs are impatient for strong leadership, intent, decisions and action. Modi they seem to think has more to show than [Rahul] Gandhi on all these counts.”

But any discussion vis-à-vis Modi is incomplete without mentioning the question of minorities, especially Muslims. Since the Gujarat riots in 2002, Modi has worked tirelessly to rebrand himself from the perceived hard-line anti-Muslim politician, to an icon of development. Recently, he has steered clear of anything that may blot his new image.

However, Modi has also sent mixed messages. For instance, in 2013, he openly proclaimed that he was a Hindu nationalist. In his words: “I am nationalist. I’m patriotic. Nothing is wrong. I am born Hindu. Nothing is wrong. So I’m a Hindu nationalist. So yes, you can say I’m a Hindu nationalist because I’m a born Hindu.” Sometime later, in relation to the construction of a Ram Temple at Ayodhya, Modi said it was essential to construct toilets first rather than temples.

With this in mind, the most contentious and sensitive issue is the riots after the Godhra incident, in 2002. Modi was accused of being complicit in the violence. Moreover, each time he has been questioned over the riots, he has either responded by remaining silent or stating that he has done nothing wrong or, if there is any evidence of his involvement, that he should be hanged. Indeed, Modi received a clean chit from a team that investigated the riots, and also by a court in Gujarat. Based on this, Modi has ruled out apologizing for the tragedy.

If all these issues are anything to go by, it will be interesting to see if the new prime minister can fulfill the people’s expectations by improving India’s economy and protecting its social fabric from sectarian violence.

Concluding Observations

So where is India today and how did it get there? The UPA coalition had been drowning in corruption, policy paralysis and a lack of vision. Amid these failures, the BJP, under Modi, won a landslide at the polls. The thrust of the election campaign by political parties was on issues championed by individuals. Modi portrayed himself as a leader of development and someone who can jumpstart a stagnant economy, while Rahul Gandhi remained largely inaccessible throughout the UPA’s ten years in power. When the latter addressed voters, what he said made little sense. It is clear why Indians chose not to back him.

Added to this, a large chunk of the Indian electorate was completely disenchanted by the ruling coalition. What the electorate saw in the UPA was a group of lawmakers with elite education, who let India down by indulging in corruption and straying from the path of progress. With respect to policy decisions, the UPA had indulged in posturing. A case in point was the Food Security Act of 2013, which provides for highly subsidized food grains to nearly 70% of the population. The problem was with timing: The legislation was passed less than a year before the general elections. The Act should have come before 2013 to ensure that those who came in its purview enjoyed the benefits they were entitled to.

Indeed, it is difficult to say if Modi is the right choice for India. But it is equally true that the electorate did not have many political options, due to corruption in the UPA. The people’s verdict overtly reflects that India wants a decisive leader at the helm. They people want change. The Indian political class and electorate need to reflect on issues such as unemployment, sectarian violence, external security threats and a failing education system. There are no easy answers for these problems. The electorate has made its choice, even if one disapproves. Now, the political class must deliver on its promises.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment

The article makes a good read. Though I do not agree on every point presented here, it is a fair and studied observation and presented in a comprehensible manner. The truth is that the so called ‘elite’ politicians of the Congress-led UPA have laid the nation’s economy so much to waste that it is going to be an uphill task for Modi, the new PM to get the nation back on the fast track. But the feeling across the nation is: If anyone can do that, it’s Modi.