By Arthur Kleinman and Hongtu Chen

Editor’s note: Populations across Asia are rapidly ageing. But few countries are prepared for the coming demand for elderly care, say Fung Global Institute Senior Fellow Arthur Kleinman and his Harvard University colleague Hongtu Chen. So far, many Asian societies have relied on families to care for their ageing relatives, but they will soon need to develop new approaches that involve more professional caregivers and community-wide solutions. Besides the financial crisis, climate change, energy shortage and conflicts over water, population ageing is probably the most significant global trend that will occur in this century across national and regional borders.

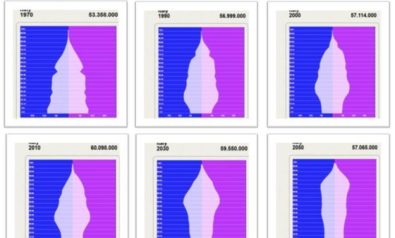

Since the 1990s, demographers have predicted that the number of elderly will expand at a speed unprecedented in human history. Right now, those over 85 years are the most rapidly growing population group in a number of societies, including those in East Asia, where more than half of the world’s elderly people reside. Economists claim that the dependency ratio — the number of elderly people over the number of working people in society — will rise, suggesting the magnitude of the demands and burden that the aged will impose on society.

An issue of great concern is how Asian countries, especially those that are undergoing rapid economic development, can provide adequate care for them. This is a daunting challenge because of the undeniable gap between the exploding demand for elder-care and the resources that are required to meet it.

First, population ageing will lead to structural change in human resources. Taking China as an example, it is estimated that the elderly-support ratio is projected to decline drastically. Right now, for every elderly person (aged 65 and above) there are nine working-age adults (ages 15 to 64); but by 2050, this ratio will be one elderly person per 2.5 working age adults. In other words, while the ageing population will triple in the next four decades, the total number of working adults will be reduced by three-quarters.

In China, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, the massive demands of ageing populations will rise at fast rates though their economies are not yet fully developed and, therefore, without the funds necessary to meet demand for care of the aged. The challenge is how to allocate limited financial resources among competing needs, such as education, health care, agriculture, and the environment, while still maintaining economic growth.

As of 2011, China had a total of 3.2mn nursing home beds, while the number of elderly people who were considering living in a nursing home reached nearly 12mn, according to China’s National Committee on Ageing. That means the total number of beds in the existing nursing homes equals only 1.8% of the total ageing population in China, much lower than the 5-7% in Western countries. The fact that 5% of Chinese over-65 suffer from dementia, makes this gap even more serious.

In Shanghai, the government-owned nursing homes, which are more affordable, are all full, and those on the waiting list need to wait for over five years before having a chance to enter. Similarly, in Chongqing where the elderly are 16% of the population, the beds available at the government-owned nursing facilities are enough for only about 1.3% of its senior population. After a few years of development of privately owned nursing homes, about 140 such facilities were opened in Chongqing. A few soon filled up, typically with wealthier aged residents, but over half of the nursing homes cannot get enough customers or face bankruptcy, making investors who were very interested in the elder care sector a few years ago, now hesitant.

The difference between well-developed nursing homes and those that are closing lies mainly in the quality of service, which is due to the massive lack of qualified care professionals. It is estimated that China alone requires approximately 10mn caregivers to meet the needs of its ageing population. However, there are only 300,000 people currently working in the field, of which less than 100,000 are professionally qualified.

In addition to a large number of trained care workers who can provide direct care and support to elderly people either at home or in a nursing facility, what determines the quality of elder care in a country is the professionals who have extensive training and experience in that area. There are at least three professions that are urgently lacking in developing Asian countries: geriatric care managers, geriatric nurses and physicians, and geriatric mental health professionals.

All developed nations have education or certification programmes for professional geriatric care managers. These professionals are in charge of care planning and coordination for the elderly with physical and/or mental impairments. They are critical for keeping the standard and quality of elder care delivered to people’s homes or through day community care centres, meal programmes or referral services. In the US alone, there are over 30,000 programmes that provide training related to geriatric care management, and a geriatric care manager typically obtains a certificate after completing training in nursing, social work, gerontology, or other health service areas.

Besides geriatric care managers, developing Asian countries are also in need of a large number of geriatric nurses and geriatric physicians to provide professional care and support to families and elderly people with Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, stroke, cancer, other common diseases of old age, as well as for those at the terminal stage of their illness.

Perhaps most needed and least available in Asia are geriatric mental health professionals. Using “professionals availability ratio” (i.e., the number of professionals per 100,000 population) as an index, developing Asian countries, especially in Southeast Asia, are among the regions in the world that have the lowest number of geriatric psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and nurses. Without these mental health professionals, who will provide professional care, support and guidance for those nearly 40% of elderly people with depression and suicidal thoughts? Or the nearly 5% of elders with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia? Or those 1% with severe and disruptive mental illness, such as schizophrenia or drug abuse?

As long as the price and quality of nursing homes are not acceptable, Asian families will naturally want to keep their elderly relatives at home. For various cultural reasons, such as values of filial piety, family responsibility and face-saving cultural attitudes, Asian families often prefer to have their elderly relatives stay at home. In South Korea — one of the world’s fast-ageing societies — more than 90% of older people with long-term care needs are exclusively cared for by informal caregivers at home. These caregivers are most frequently a spouse, daughter-in-law, daughter, or son, or paid care worker. In other Asian countries, such as Thailand, India, and China, the majority of elderly people also expect to receive their long-term care at home.

Is this a realistic expectation?

Currently, in Shanghai and Beijing, about 34% of the elderly are living alone or living separately from their children. In rural China, because of the large-scale migration of workforce to cities and abroad, over 38% of the elderly are “empty nesters”; a quarter of them live alone. Most of these empty nesters do not want to burden their children; in any case, most of their children work far away, and return home only for very brief visits.

Even if those adult children abandoned their jobs, would they be able to provide long-term care for their elderly parents? In only a few years, the first generation that gave birth under China’s “one-child policy” that began in 1978, will reach 65 years of age. This means that their married children, who are likely to be a middle-aged couple, will have to provide care to four elderly parents, most of who will live with them. In another two decades, many Chinese middle-aged couples will have to provide care for four parents who are in their late sixties, and eight grandparents in their fragile eighties.

By 2030, the traditional elder-care model that relies on one’s own children will no longer work and will have to be abandoned in China. New models, possibly built on community-based social capital or collaborative care among families in the neighbourhood, will have to emerge to rescue China’s future from the pressing burden of caring for the elderly.

*[A version of this article was originally published by Fung Global Institute on April 24, 2012.]

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment