This article explores in two parts the prospects for dispute management through the lens of claimant states and the interest of non-claimant states.

Part 2 is "Balance of Interests Between Claimants States and User States"

The Role of the Third Party Forum under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea(UNCLOS)

All of the coastal states of the South China Sea (SCS) except Cambodia have ratified the UNCLOS. UNCLOS is the principal instrument in providing a legal ground-work on which to build sound and effective regulations to the different uses of the ocean. It does not specify in detail when and how fishers can harvest living resources in the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of coastal States or what the terms of leases for deep seabed mining will be. What it does create are (sometimes contentious) procedures for arriving at collective decisions about such matters.

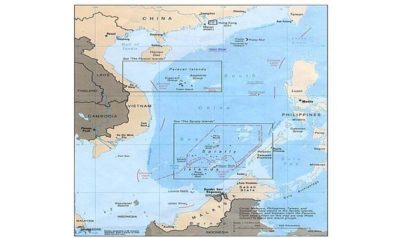

The South China Sea (SCS) dispute is complex and the settlement is challenging. The major conflict in the SCS arises from the territorial dispute over the Spartly Islands and the maritime borders. The core conflict over the islands’ regime involves three elements: the sovereignty of the islands, the zones generated thereby and the maritime delimitation. The territorial disputes involve China, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei.

The competition over sovereignty seemed to quiet down for a while after the parties signed the “Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in The South China Sea” (DOC) in 2002. The Philippine Baseline Bill in February 2009 stirred a new round of debate amongst these parties. Can the third party compulsory mechanism of maritime dispute settlement under the UNCLOS framework, through the International Court of Justice or the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, play a critical role in this game?

It seems unlikely that the countries involved would resort to the third party forum for the law excludes sovereignty disputes from the compulsory procedures. In the case of the SCS, China has made a declaration according to this provision. Other claimant states may, at any time, make similar declarations as well. Disputes regarding the zones and maritime delimitation could not be solved before the sovereignty is addressed.

However, UNCLOS does give the court and tribunal a role to play in the dispute. A state may raise the question of whether a piece of land is a rock or an island without a tribunal or court being involved in the actual maritime delimitation. Such a decision can then be used by a state to influence negotiations over the boundary, even though the law excludes disputes related to the definition of a feature from the compulsory dispute settlement.

From DOC to Code of Conduct (COC)

China and ASEAN signed the DOC in 2002. They hereby confirmed to promote pragmatic cooperation and promised to ultimately reach a code of conduct on the South China Sea. 2011 has witnessed positive progress in the implementation of the DOC. In July, China and the ASEAN countries adopted the Guidelines for the Implementation of the DOC, which paved the way for practical cooperation in the South China Sea. In November 2011, China reiterated its efforts to work together with ASEAN countries towards the consensual adoption of a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea. The same month, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao announced that China would set up a China-ASEAN maritime cooperation fund with an amount of RMB 3bn.

Confidence building

There is a need for region-wide mechanisms or institutions to share information and manage conflicts in the South China Sea. The 1998 Military Maritime Consultative Agreement between the United States and the People’s Republic of China could serve as a model. It has also been cited as a mechanism through which incidents such as the Hainan Island incident might be discussed. The Indonesia workshop process is widely recognized as a venue for discussions and the promotion of cooperation among parties with an interest in the South China Sea.

More working groups on cooperation projects, marine research, resources, safety of navigation and legal matters should be established. Academic workshops should be held to clarify the application of UNCLOS to the issues in the South China Sea. An informal commission of international maritime legal experts may be convened to explore how UNCLOS applies to the South China Sea and to identify mechanisms for settling overlapping claims.

Regular military-to-military cooperation should be established in search and rescue. Informal dialogue should be promoted among military representatives on standard operating procedures and rules of engagement. Uniform international safety standards for vessels and aircrafts transiting the region should be established and joint patrols should be promoted to respond to illegal fishing and piracy.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment