In East Africa, particularly in the Horn of Africa, several crises are currently overlapping. For some time now, climate events such as droughts have been creating major food supply bottlenecks in addition to fueling conflict and war.

These issues are being exacerbated by a locust swarm that originated in Yemen and has been growing exponentially since October 2019. One of the reasons for the phenomenon is the increasingly frequent climatic event known as the “India Ocean Drop,” which has led to high levels of humidity and flooding in recent years. In June, locusts are expected to multiply a further 500 times, which poses a massive threat to crops in the coming harvest, previously forecast to be profitable.

The News Media and Public Health Crises

COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, comes as an additional problem, and it is unclear how widespread it has already become in East Africa, as there has been little testing. But the official figures are rising, and the number of unreported cases of infection is probably high.

What is certain is that the confluence of the coronavirus pandemic with other crises, as well as the responses to them, will lead to a cascade of problems — a dynamic known from the policy area of civil protection. As a result, a doubling of the number of people affected by extreme hunger has to be expected.

Exacerbating the Food Supply Crisis

Health policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis are taking place within a context of extremely limited medical capacities. In Somalia, there are 0.028 doctors per 1,000 inhabitants, and in Kenya, this figure stands at just under 0.2. (This is compared to Germany at 4.2.) As in other countries, efforts are being made to expand health capacities and implement hygiene rules. However, the latter is often limited due to poor water infrastructure.

In reaction to these limitations, countries in East Africa rely heavily on border closures, travel restrictions and strict lockdowns to flatten the infection curve of the virus. However, it is precisely these measures that make securing the food supply and controlling the locust population more difficult, which in turn leads to further food shortages.

This shows that an approach that focuses only on one crisis can exacerbate other crises. There are also different crisis dynamics in urban and rural areas, for which individual responses must be made. At the same time, they influence each other and must be considered together.

COVID-19 and the reactive measures to it reach the populations in cities first and fastest. Here, many of the people who work in the informal sector often live in very confined spaces. They are particularly hard hit by the mobility restrictions, as they are unable to generate income, build up food reserves or provide for their families. In urban centers, however, it is in principle easier to deliver aid to the suffering populations than in the countryside — even though restrictions brought about by the coronavirus can disrupt the market connections to rural producers with limited mobility.

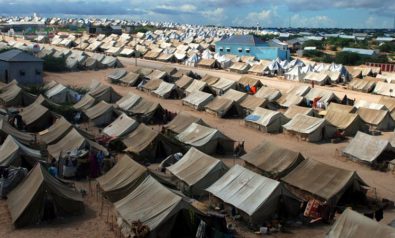

The other heavily affected group consists of refugees. In East Africa, there are more than 10 million internally displaced persons who are receiving hardly any support. Refugees living in camps are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, but unlike the day laborers in the cities, they are supplied by external aid organizations.

The lower population densities in rural areas and the widespread subsistence economy tend to make the populations there less susceptible to health and supply risks than city dwellers. However, the majority of farmers still have to buy additional food because their own harvests are not sufficient. They are thus also affected by price increases and supply bottlenecks for food as well as for seeds and fodder, which can be due to the locusts as well as coronavirus-related border closures and mobility restrictions.

Reconciling Health Protection and Security of Supply

How should solutions be tailored to do justice to this complex situation with its many interdependent crises and problems? First, government agencies must find ways to connect towns and the countryside to supply markets in towns and cities and enable providers in the countryside to make a living.

Second, the experience of Africans in dealing with the Ebola virus can also be drawn on, according to which health protection and security of supply could be well reconciled. In West Africa, for example, there were collection points for the domestic trade of food, in which only a few people — using personal protective equipment — were involved.

Third, East Africa and the Horn are also pioneers in cashless financial transactions. This makes it possible to provide direct financial support to endangered population groups instead of direct food aid. Aid is thus distributed more fairly, the population can decide for itself how best to use the money, depending on the local situation, and the domestic market is strengthened.

At the regional level, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development could provide coordination for the crisis response. Based on excellent networking, it has proved to be essential for information about COVID-19 in the region.

International efforts should be made to ensure the trade in food and feed, insecticides and drones; in particular, trade restrictions on these essential goods must be dismantled. It must also be ensured that aid workers can move freely on the ground. Rapid financial assistance is also needed to respond to the expected increase in locust swarms, something that has been decided now by donors such as the World Bank and the European Union.

In all local, regional and international approaches, the long-term problem of climate change should be considered an underlying major driver for several crises.

*[This article was originally published by the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), which advises the German government and Bundestag on all questions related to foreign and security policy.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.